OUT

Photograph by Derek Lapsley

OUT

Photograph by Derek Lapsley

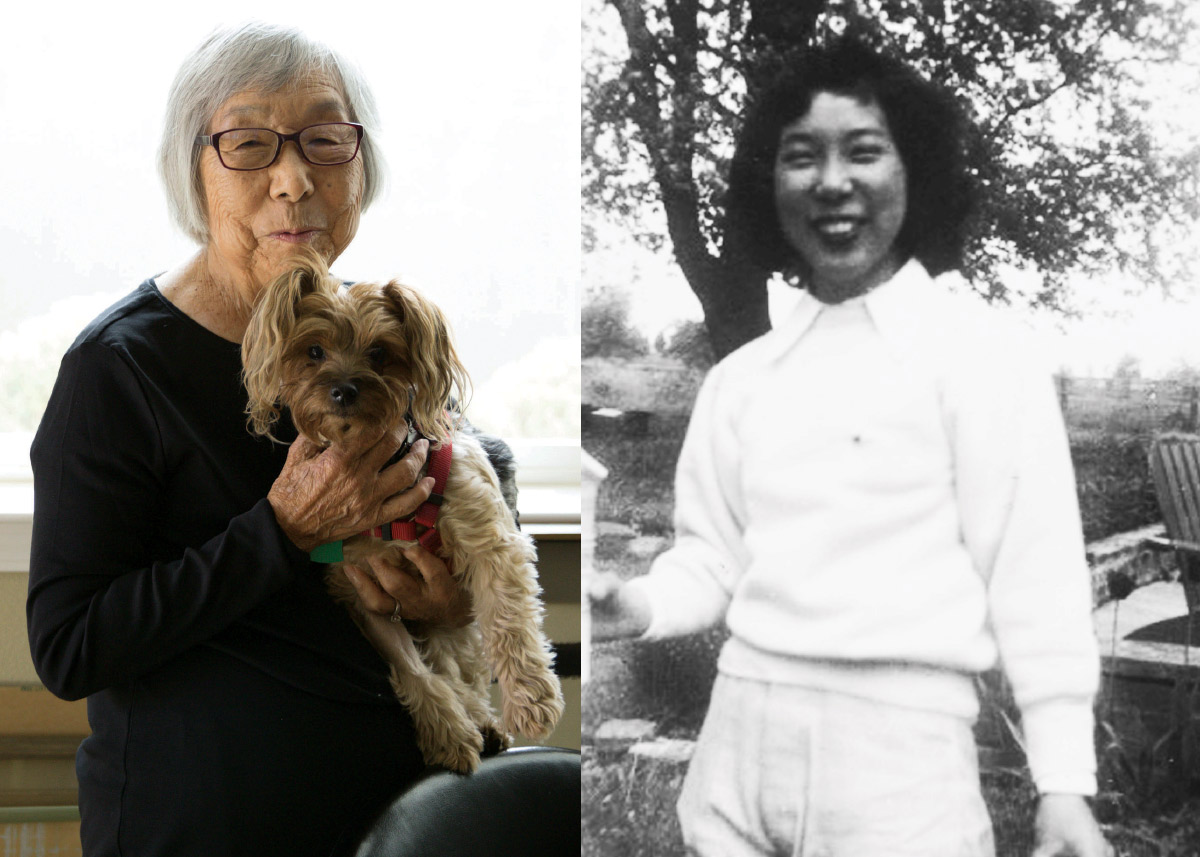

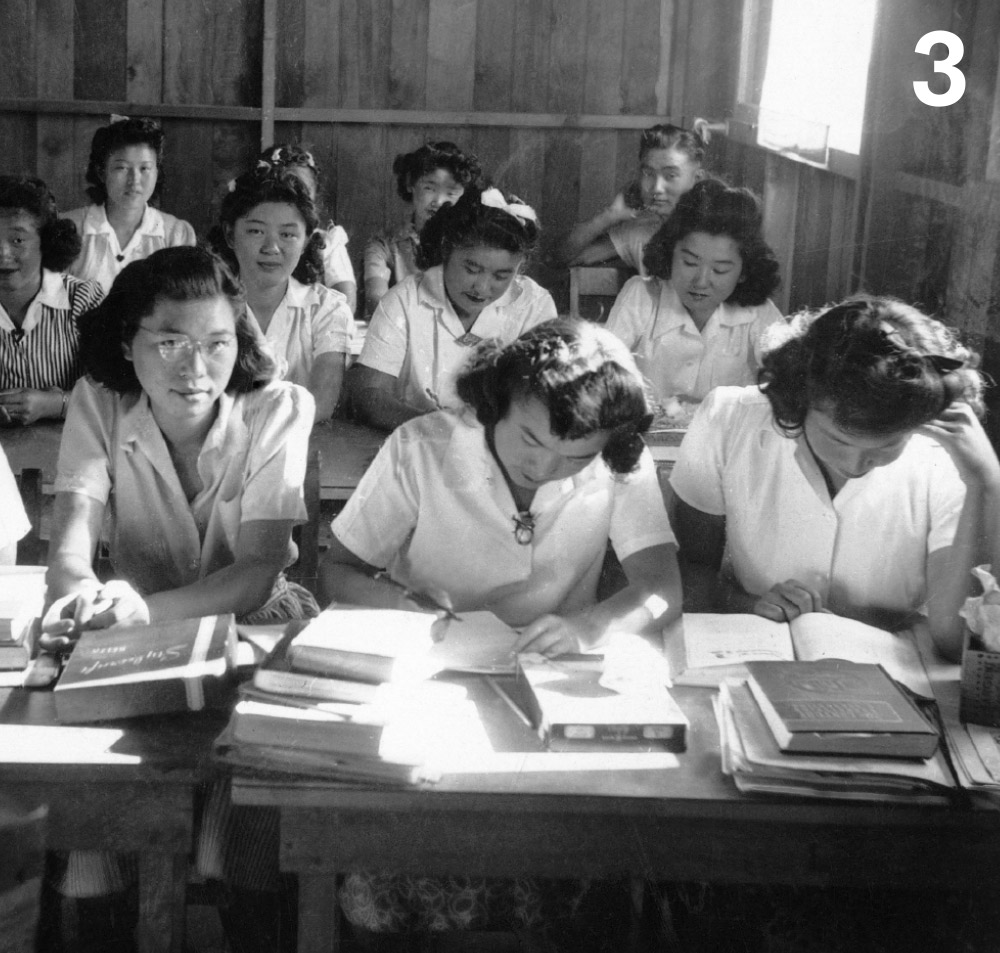

er life was suddenly interrupted when the U.S. government plucked her out of her world and sent her to a desert relocation camp. Two years later, in a twist of nearly equal proportion, her life resumed — at Bucknell University. Now age 93, she’s the only known Bucknellian alive to share her story of being detained in a Japanese American prison camp during World War II.

In the 1940s, Sachiye “Sachi” Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48 was an all-American girl living in California’s lush Central Valley. Her parents had been born in Hiroshima, Japan, but now were hard-working grape farmers in Sanger, a town known for the General Sherman, a 267-plus-foot sequoia so majestic that a 1926 act of Congress designated it a National Shrine. She was a serious student, expected to follow the customary plan of her day: graduate from high school, attend a local college, then marry.

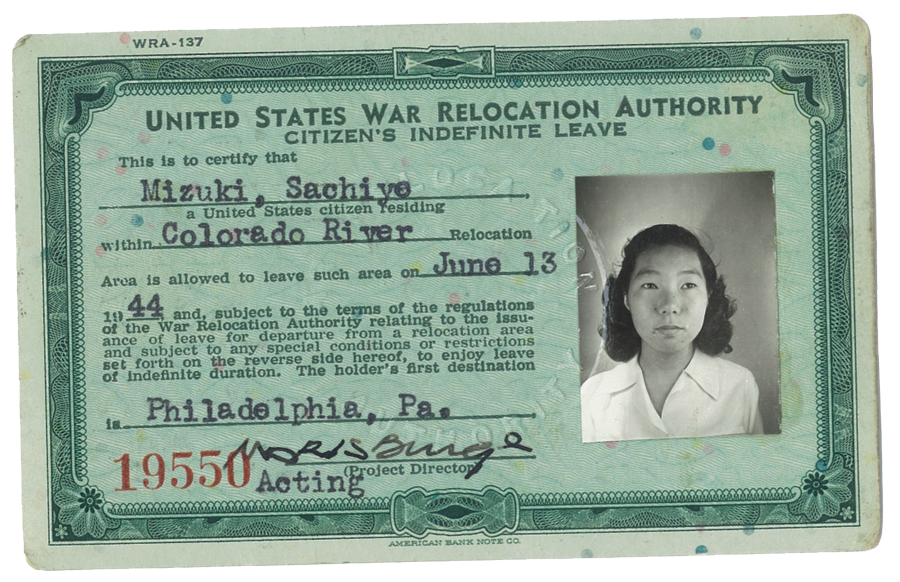

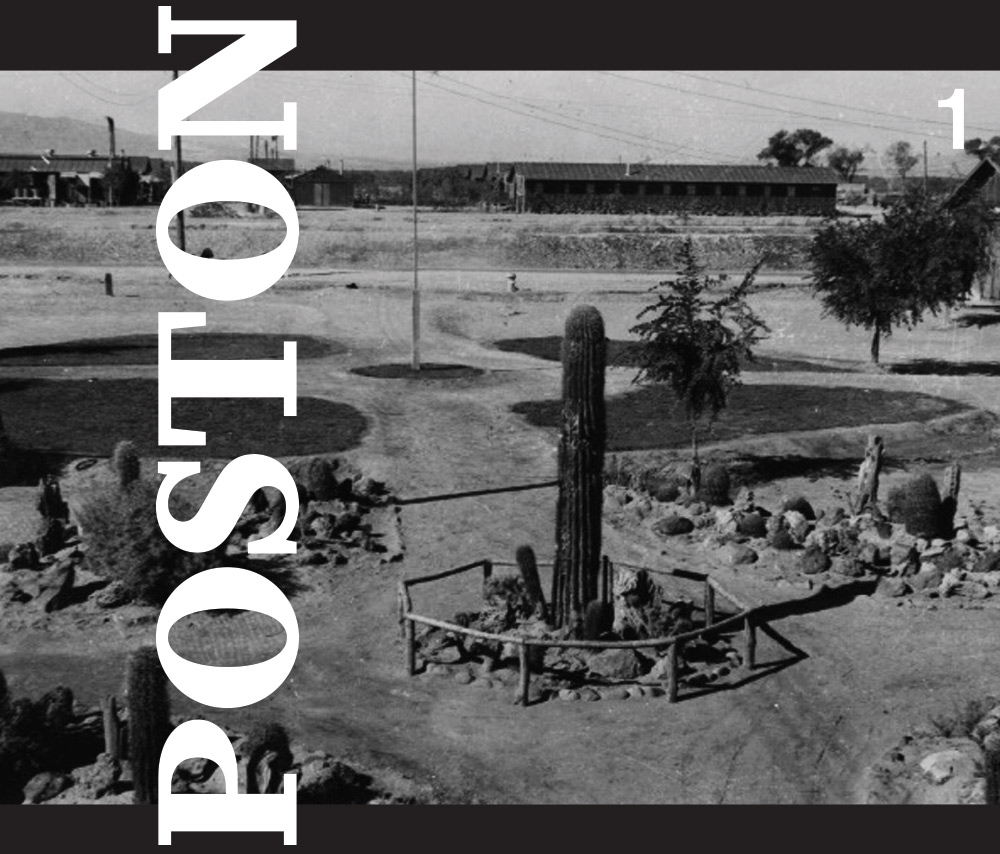

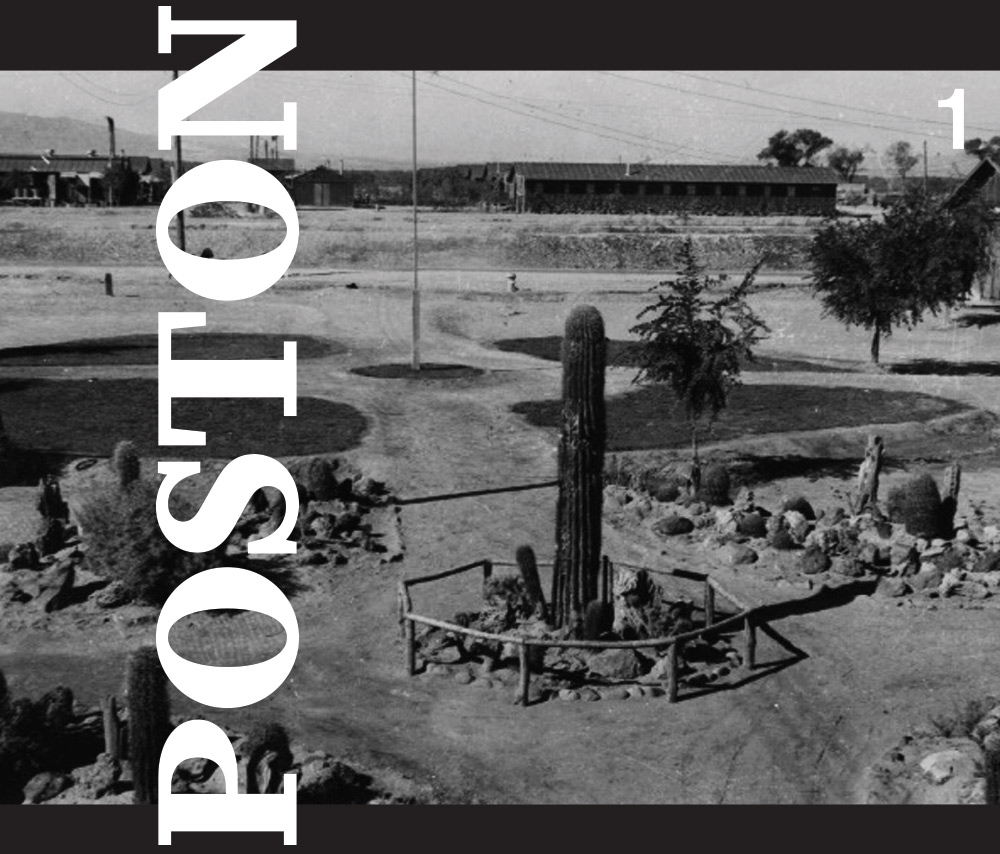

But on Dec. 7, 1941, the customary disintegrated like all that smoke enveloping Pearl Harbor. After that day, Kuwamoto’s trail would lead not to Fresno State, but to two years’ incarceration in a desert camp operated by the federal government to contain Japanese Americans. (At the time, the site also housed another disenfranchised people — the Colorado River Indian tribes.)

The Pearl Harbor attack that brought the United States into the war also upended life for the Mizuki family of six. Her father had immigrated and settled in the Japanese American community of California’s agricultural capital some years before her mother came to America, Kuwamoto says. Kuwamoto was the youngest of the couple’s four children, called Nisei, a term for American-born children of Japanese immigrants.

The Mizukis knew the Pearl Harbor attack didn’t bode well for Nisei or their immigrant parents, called Issei. “There was already a program of discrimination against Asians, and all Japanese Americans were assumed to be disloyal,” Kuwamoto says. After Pearl Harbor, “We couldn’t buy property or become citizens until after the war ended. There was uncertainty about what would happen to all of us.”

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 stipulating that, “for reasons of military necessity,” Japanese Americans living in Pacific coastal areas would be relocated to inland camps. Eventually, 120,000 Japanese Americans, including 70,000 who were American citizens, were rounded up and removed to 10 camps. Two of those camps, Gila River and Poston, were built on Native American reservations in Arizona.

“We had about a month to prepare,” Kuwamoto says. “We could only take a suitcase, what we could carry.” A Caucasian neighbor agreed to look after the farm, crops and beloved family dog.

Life in Poston II was constricting, especially for the men, she says. “After working so hard to support the family, they wanted to find something useful to do. My father helped the community by making tofu and other things. He tried to make a life. He picked up desert ironwood that he polished and left in its natural state — I still have a bowl that he made. He also polished stones to make into pins.”

Her older brothers also sought ways to keep busy, one gaining a pass to work on a sugar-beet farm, the other exiting the camp gates — as a U.S. Army draftee.

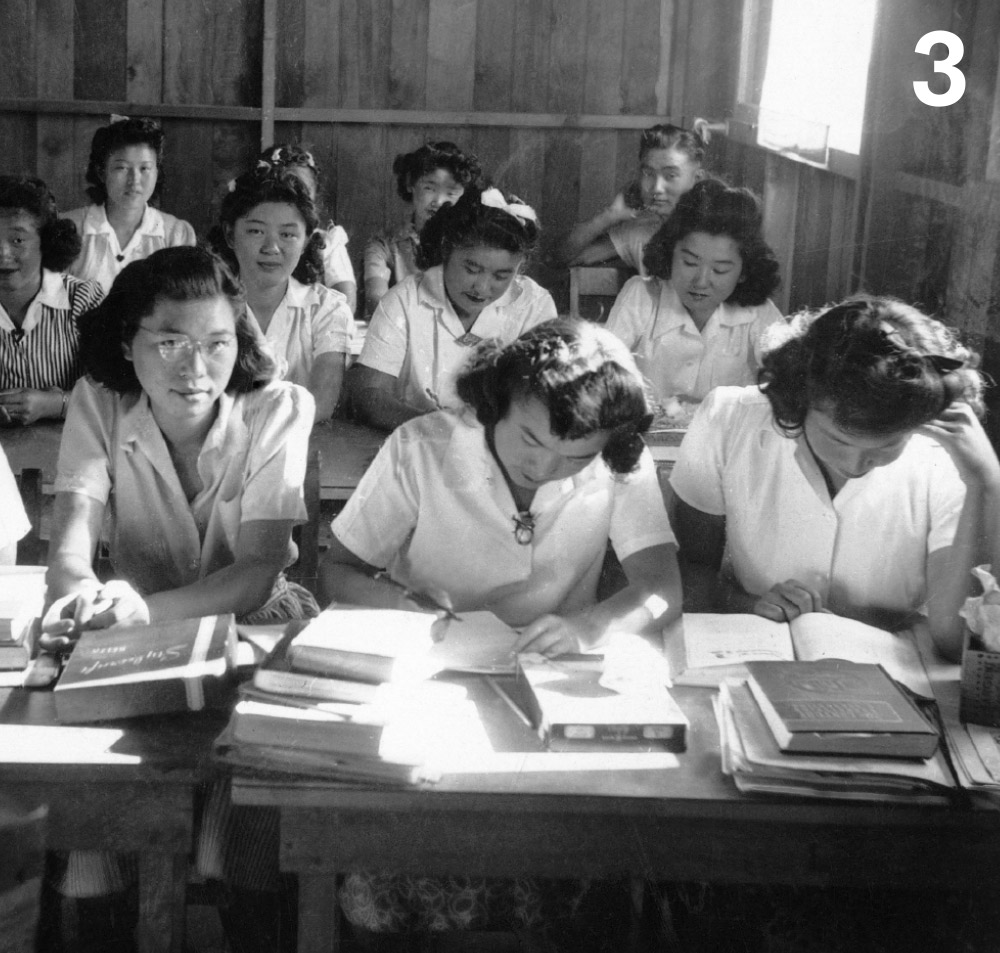

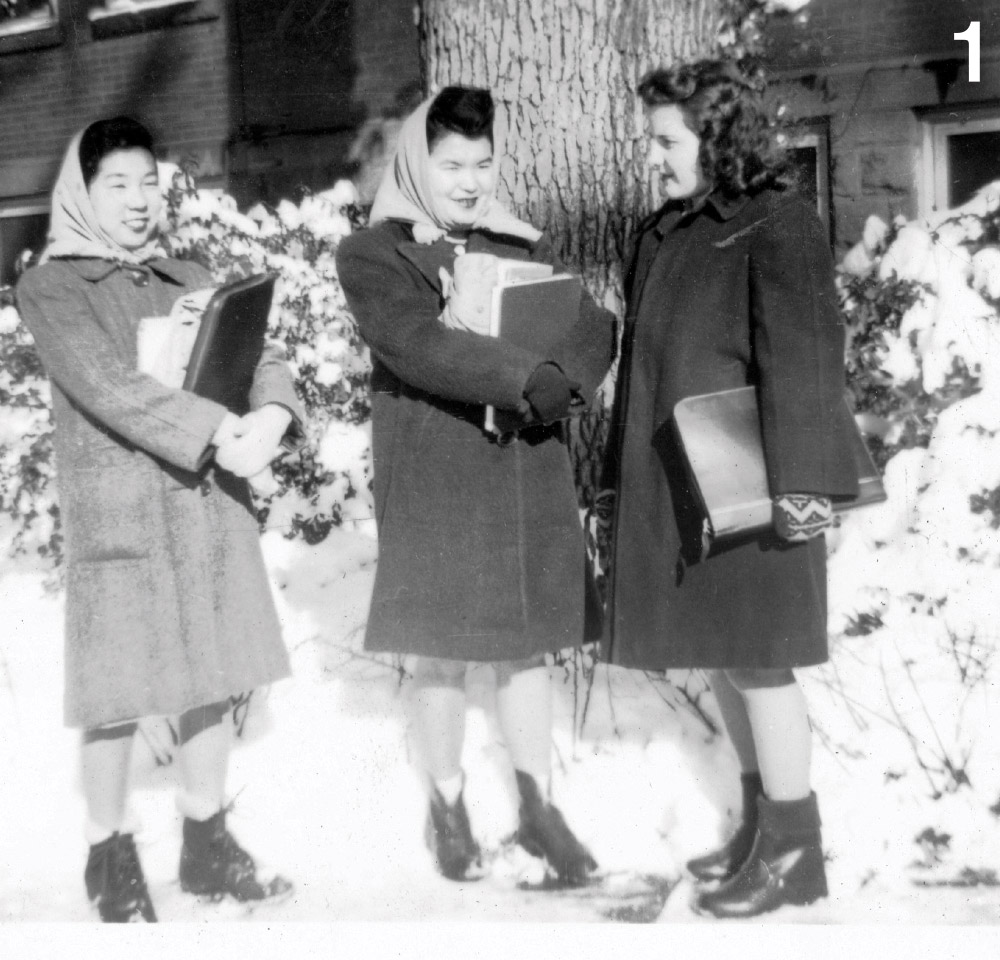

“My work was going to school,” Kuwamoto says. “There were a couple hundred of us in the high school. I was interested in English and art. I thought I might be a journalist.” Although the Native Americans and Japanese Americans shared a barren scrap of land, Kuwamoto doesn’t recall the two groups mingling.

On Feb. 10, 1944, The Bucknellian published a plea for students to accept and welcome the Nisei, not just to tolerate them. The article noted that students accepted for the program had to pass an FBI background check and profess Christianity — practitioners of “Japanese religious doctrine” would not be released.

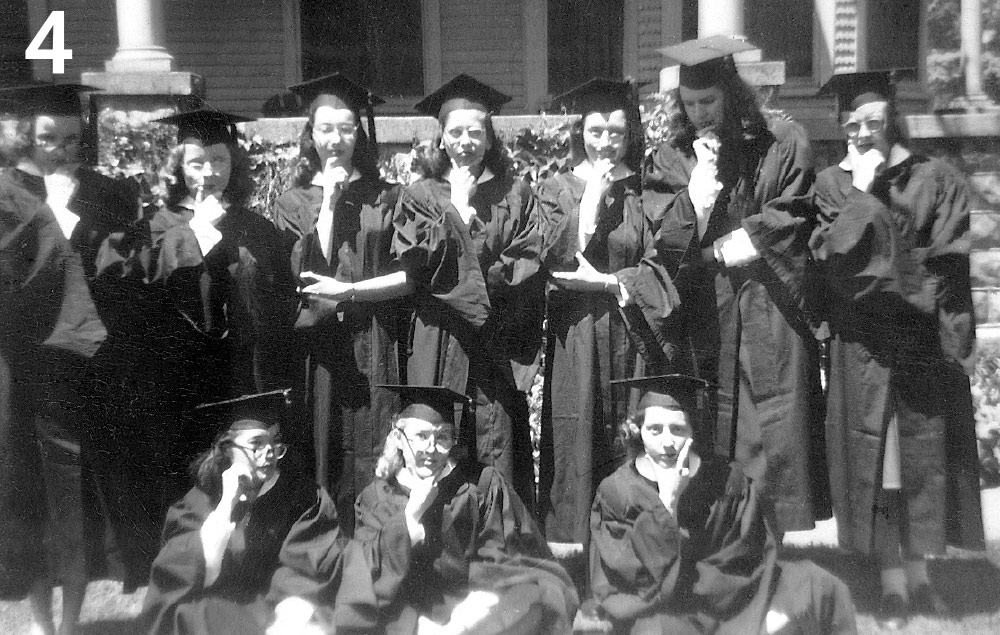

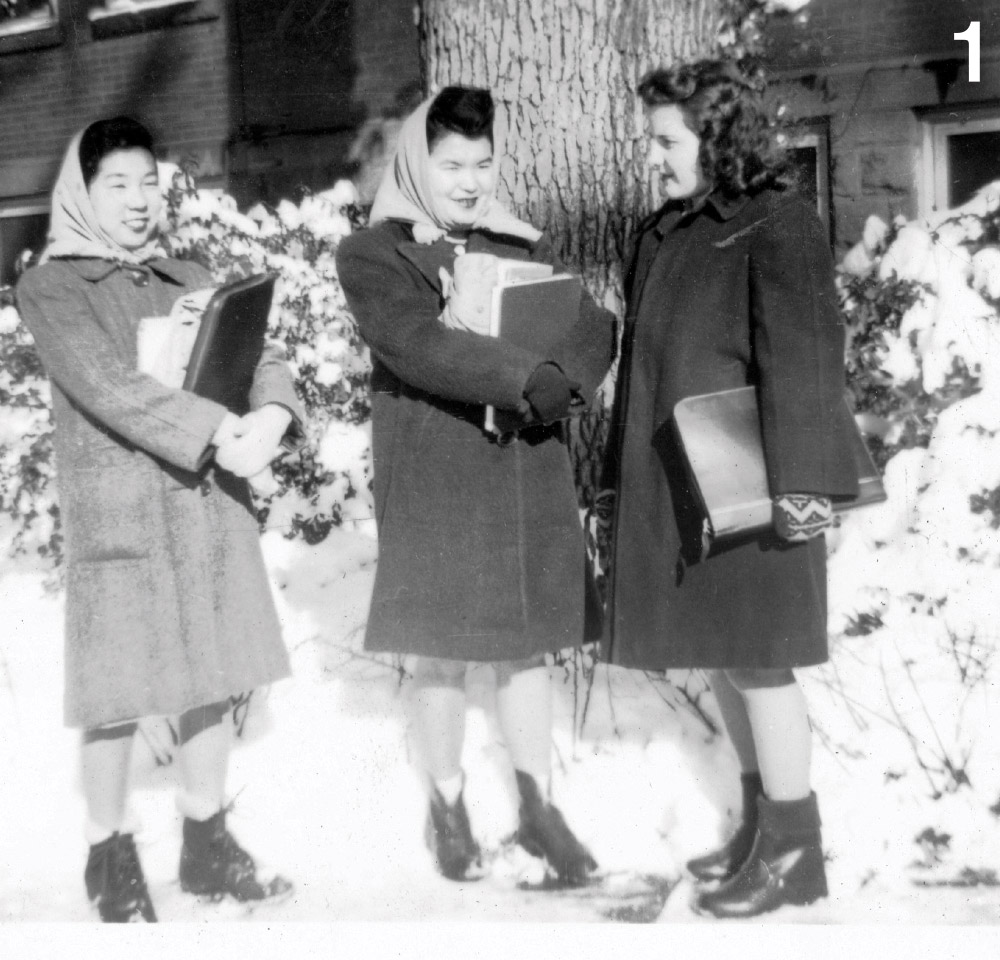

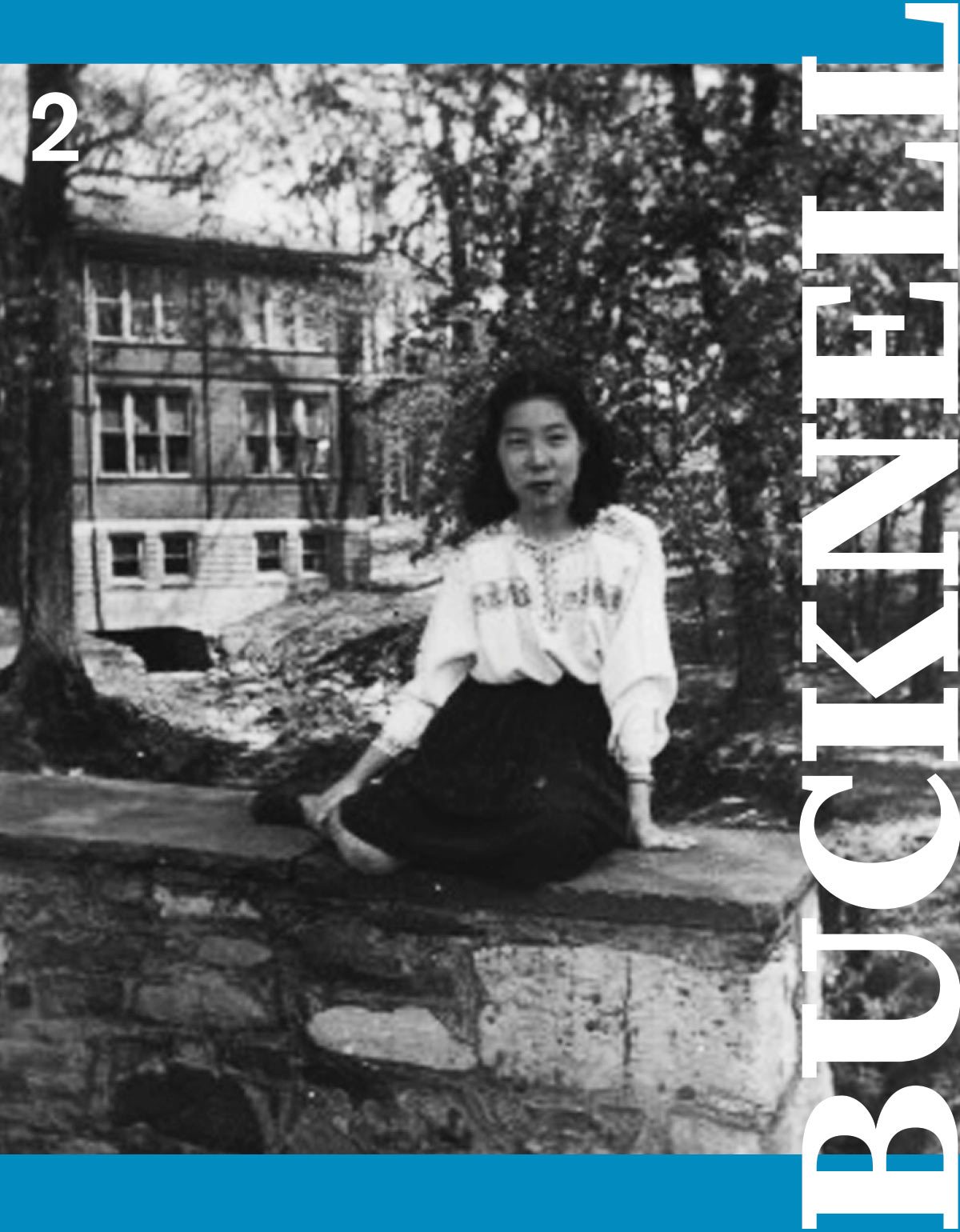

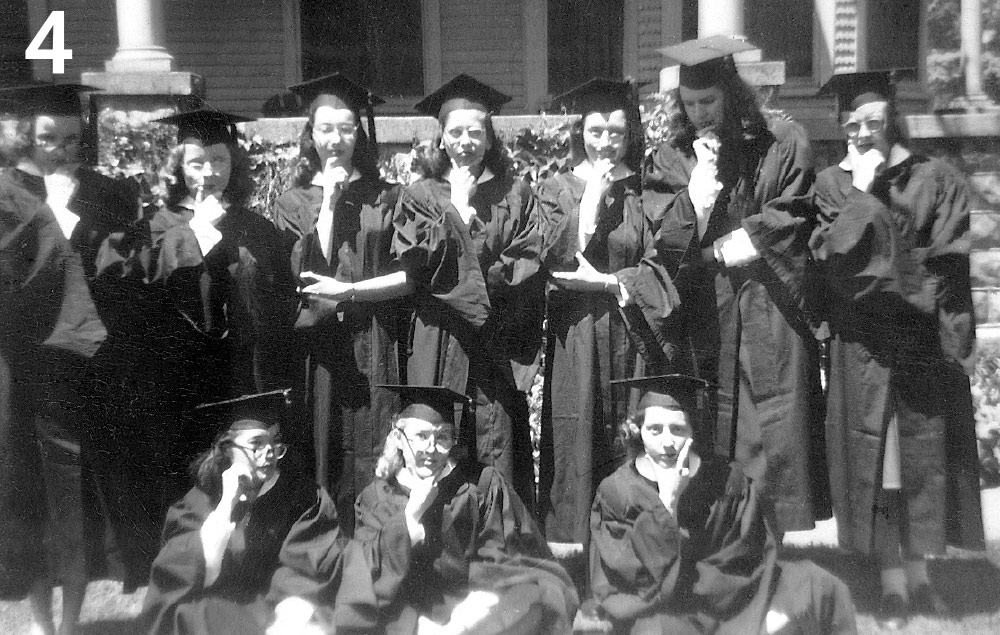

Photo 1 courtesy of Sachiye Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48. Photos 2, 3 and 5 courtesy of Kiyo Tabery. Photo 4. Hikaru Carl Iwasaki/National Archives and Records Administration.

Photo 1 courtesy of Sachiye Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48. Photos 2, 3 and 5 courtesy of Kiyo Tabery. Photo 4. Hikaru Carl Iwasaki/National Archives and Records Administration.

Photos 1, 3, 4 and 5 courtesy of Kiyo Tabery. Photo 2 courtesy of Sachiye Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48.

Photos 1, 3, 4 and 5 courtesy of Kiyo Tabery. Photo 2 courtesy of Sachiye Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48.

In a letter dated April 22, 1944, Christian Association secretary Forrest Brown pressed the issue with Bucknell President Arnaud C. Marts. Three days later, Marts responded, perhaps illuminating why the administration was reluctant to admit Nisei students. Marts feared the Lewisburg community would not welcome Japanese Americans, further enflaming a delicate situation. Marts wrote that he was already allaying “gossips and whispers about a man as well known and highly endorsed as Dr. [Ernest] Meyer,” a social sciences professor originally from Germany, now regarded as the enemy.

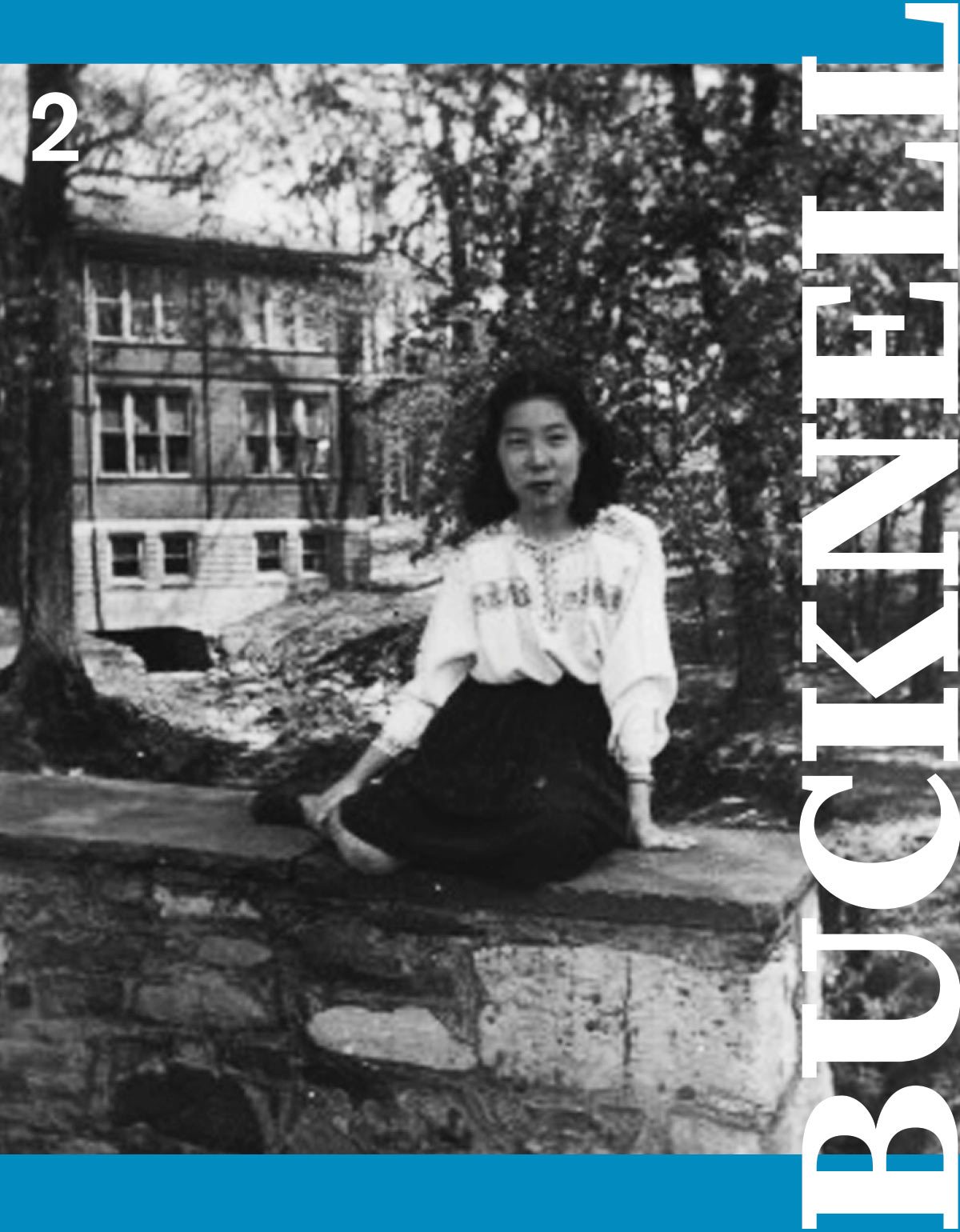

Nov. 1, 1944, they arrived, set for the start of a new life of freedom. The Nisei women shared a Larison Hall room that Kuwamoto recalls “was not a regular dorm room. It had huge windows that we had to make curtains for.” At first, Kuwamoto and Sakasegawa were “sort of a pair,” both waitressing in the dining hall to earn tuition money.

But after their first year, Kuwamoto gravitated to students interested in art and English. She was features editor for The Bucknellian and a copy editor for L’Agenda. Sakasegawa, a sociology major, was vice president of the Christian Association and vice president and chairman of the student government’s House of Representatives. Both women were also officers in the NAACP, whose adviser was Professor Cyrus Karraker, history. Kuwamoto recalls Karraker as being very supportive and “one of the few people who knew about the Japanese American experience at the time.”

In spite of Marts’ early concerns, Kuwamoto does not remember any prejudicial behavior. “We were just regular new students. If there was any feeling of discrimination, I did not experience it myself. People went out of their way to be helpful and make sure we fit in.” (For more on Sakasegawa, who died in 2010, see Page 42.)

When Kuwamoto left AFS in 1968, she had helped build the organization into one that has launched cross-cultural experiences for more than 400,000 students. She was ready for a new challenge that presented itself when Kuwamoto was visiting family near Fresno. Satoshi Kuwamoto, who owned a hardware store, was a friend of her father. “He had three children, and his wife had passed away,” she says. “I met him, and he decided I should help with the kids, so we got married, and I took over as the stepmother for his three kids.”

During those years, until she retired in 1992, Kuwamoto was regional director for the Japanese American Citizens League, the nation’s oldest and largest Asian American civil rights organization. Among her duties was running a Fresno center for elderly Japanese Americans. Her husband, with whom she enjoyed traveling to Japan and elsewhere, died in 2016. Kuwamoto recently relocated to a cottage in a senior community in Clovis, not far from her childhood home, where her stepchildren look after her.

Still, she’s careful when comparing her two years at the Poston camp with the experience of other marginalized groups that have found themselves suspected, separated and detained in camps.

“I feel that to call them concentration camps is an insult to the real concentration camps in Europe,” Kuwamoto says. “Ours was not that kind of camp. We were citizens and noncitizens incarcerated without due process, but it did not go to the extreme the concentration camps did. It was sort of a prison, though. We were incarcerated, and our rights were taken away.”

Kuwamoto says as bad as that was, it offered her the opportunity to attend Bucknell, and that positioned her to become a global ambassador for cross-cultural understanding — a role she couldn’t have anticipated, but still embraces.

“If the war hadn’t happened, I probably would have stayed in Sanger and gone to a local university or one of the UC campuses, gotten married and lived a normal life.”

Special thanks to Isabella O’Neill, head of Special Collections/University Archives; Professor Adrian Mulligan, geography; and Julia Stevens ’20 for their research assistance.