The University Observatory stands tall as snow dusts the campus.

The University Observatory stands tall as snow dusts the campus.

by Susan Lindt

Burling volunteered with children in the U.S. and Spanish-speaking countries during high school and later through Bucknell’s Office of Civic Engagement. She designed her AmeriCorps service to learn more about Hispanic culture in the United States.

With an eye on foreign service, Burling will soon start a master’s in intercultural and international communication at American University’s School of International Service. By design, she survives on food stamps, a stipend of about $285 a week and wages from her weekend job. She wants to know the challenges of the families she serves.

“I care about my work; I want to see it from a minimalist, on-the-ground point of view,” she says. “If there’s any time to do what I’m doing, it’s now.”

Burling volunteered with children in the U.S. and Spanish-speaking countries during high school and later through Bucknell’s Office of Civic Engagement. She designed her AmeriCorps service to learn more about Hispanic culture in the United States.

With an eye on foreign service, Burling will soon start a master’s in intercultural and international communication at American University’s School of International Service. By design, she survives on food stamps, a stipend of about $285 a week and wages from her weekend job. She wants to know the challenges of the families she serves.

“I care about my work; I want to see it from a minimalist, on-the-ground point of view,” she says. “If there’s any time to do what I’m doing, it’s now.”

Canandaigua, N.Y.

Mr. Burns said that “no consequential discussion of ecology can occur without serious consideration of population growth.”

This reminded me of the famous and discredited book, The Population Bomb, published in 1968 by Paul Ehrlich. This sensational and alarmist book warned of the perils of “overpopulation,” predicting worldwide famine, death, societal upheaval and devastating environmental deterioration within 20 years.

The espoused Malthusian Theory of Population, predicting exponential population growth and arithmetic food supply growth, proved to be fundamentally flawed. The theory was not only wrong but also resulted in horrific violations of human and natural rights that disproportionately harmed the poor and developing nations.

Tragically, the radical overpopulation “solutions” promoted abortion, euthanasia and forced sterilization around the world. Hopefully, we should learn an important lesson. Anti-human themes should have no place in modern ecology and environmentalism.

Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla.

I read with particular interest the story “How the Bison Lost Their ‘S.’ ” As a member of the Bucknell Marching Bison Band, I remember well the consternation a section of us had about the grammar of a university of our caliber using “Bisons” as a mascot name. Due to the instigation of trombonist Paul Schneeloch ’87, many of us crossed out the S on our uniforms, which were glorious, double-knit polyester from the earlier decade when Bisons was in vogue. Participating in the Marching Bison Band as a flag-squad member is a favorite part of my fond memories of my Bucknell years. It is nice to know that, though I think we were wholly unaware of Brad Tufts’ initiative, the marching band supported the name change in our own way at the home games in those same years!

On a side note, thank you also for the photo of “our” 1985 Bucky. Those of us who know Bucky personally can tell you that in 1985–87, Bucky was a nearly undefeated foosball player, a gentleman and a scholar.

Nags Head, N.C.

We intend to banish the grays with this issue of Bucknell Magazine, our first as we enter a new decade. We decided to center this issue on a common theme, hope. And we hope that reading our cover story about alumni who have braved the gravest challenges and moved with new strength into a more hopeful future will help you view your own obstacles in a new light. In another feature, eight faculty and student essayists offer differing perspectives on where we can find hope in 2020. And, finally, the hope that Bucknell extended to two Japanese American students during World War II, freeing them from a desert detention camp to a new life in green central Pennsylvania, should make the winter grays go away.

Let us know if this look at hope resonates with you.

The editors reserve the final decision to publish and edit any letter — there is no guarantee that all letters received will be published.

All letters must be signed. The maximum length is 300 words. The editors reserve the right to edit letters for clarity and space. Writers may be asked to submit revised versions of letters or to approve editorial changes made by the Bucknell Magazine editor. After two issues, the debate on any topic will conclude. Views expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editors or the official views or policies of the University.

After a nearly fatal accident, Matthew Wetschler ’02 paints his way to recovery.

Photograph by Saroyan Humphrey

Volume 13, Issue 1

Heather Johns

Editor

Sherri Kimmel

Design

Amy Wells

Associate Editor

Matt Hughes

class notes editor

Heidi Hormel

Brad Tufts

Emily Paine

Susan Lindt

Bryan Wendell

Mike Ferlazzo

Editorial Assistants

Shana Ebright

Julia Stevens ’20

Website

bucknell.edu/bmagazine

Contact

Email: bmagazine@bucknell.edu

Class Notes:

classnotes@bucknell.edu

Telephone: 570-577-3611

(ISSN 1044-7563), of which this is volume 13, number 1, is published in winter, spring, summer and fall by Bucknell University, One Dent Drive, Lewisburg, PA 17837. Periodicals Postage paid at Lewisburg, PA and additional mailing offices.

Permit No. 068-880.

Circulation

53,000

Postmaster

Send all address changes to:

Office of Records,

301 Market St., Suite 2

Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837

© 2020 Bucknell University

Please recycle after use.

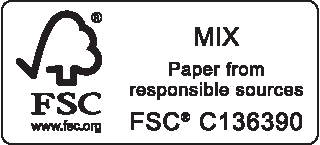

The dangers of vaping and e-cigarettes briefly claimed headlines in fall 2019, when more than 40 deaths and 2,000 cases of serious lung ailments were linked to vaping.

“We’re the first to show the relationship with carbon monoxide as a function of the power of the e-cigarette,” says Professor Dabrina Dutcher, chemical engineering and chemistry, who began studying e-cigarettes with students three years ago. “The study proves that we really don’t know what’s coming out of e-cigarettes, but we now know there are potentially harmful chemical reactions.”

New Berlin, Pa.

New Berlin, Pa.

Late last summer, on Lake Hopatcong, N.J., Matt Rulon ’21 went wakeboarding for the first time. He managed to stand on the board — a tall order for a beginner — but the more experienced riders with him weren’t so satisfied. The wakeboard they rode was too stiff and too heavy for a quality ride. Rulon’s mission for the next year was to make it better.

What They’re Doing

Supported by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, Rulon and fellow mechanical engineering major Matt Sennett ’21 are helping snowboard manufacturer Gilson Snow expand its product line into wakeboards. The students are manufacturing innovation fellows with Bucknell’s Small Business Development Center (SBDC). With support from mechanical engineering professors Nate Siegel and Craig Beal, they’re creating prototypes at the company’s New Berlin, Pa., factory and testing them with equipment at the College of Engineering.

The program partners first-year student scholars from more urban and ethnically diverse areas with seasoned students who, as peer mentors, offer support and resources to assist new students in navigating life on campus and in rural Lewisburg.

“Bucknell is quite a change for some students,” says Rosalie Rodriguez, director of Multicultural Student Services. “Even those who grew up in predominately white areas were still able to go home to their families at night and have their culture and heritage reaffirmed. Although our under-represented minority population has grown, students potentially can still be the only person of color in their residence hall, on their sports team or in their classes. They don’t get that affirmation of their personhood, culture or value system mirrored back to them as often as other students might.”

“I’m thrilled at the prospect of working with a talented team that has done a wonderful job of laying the groundwork of a communications approach that is similarly strategic and thoughtful,” Glover says.

Glover comes to Bucknell from the State University of New York at Geneseo in western New York, where she was chief communications and marketing officer overseeing a rebranding campaign that included the design and rollout of a new university logo and parent communication strategy.

A graduating senior gave me this book. Susan Cain, a self-claimed introvert, convinces us that introverts can thrive in the world that seems to be dominated by loud extroverts. This book challenges us to rethink what it truly means to be a model Bucknellian, making it a pertinent read as Bucknell welcomes diversity and experiences a shift in student demographics and backgrounds.

A student recommended this book to me. I was intrigued to take a deep dive into the life of one of our most illustrious alumni, whose drive, guts, instincts and care for others is awe-inspiring. This captivating memoir also reminds us that we can create our own definition of success and achieve it by working hard and cherishing relationships.

A colleague gifted me this book when I sought advice for my mid-career struggles. Using the framework of engineering design, the authors help readers craft — and act on — the best versions of themselves. The book is great not only for career and professional development, but also for reviewing one’s life choices and happiness.

Retired ExxonMobil engineer Lawrence Casey first signed up for dance lessons to learn a few casual moves he could try at country-western clubs. He began pairing with a professional dancer and has won Country Western Pro-Am championships around the globe. Now he mainly competes in International Latin and has been known to do the two-step at the supermarket.

b. Cha-Cha

c. Waltz

b. Emmylou Harris

c. Miranda Lambert

b. Getting to travel to competitions around the world

c. The applause

(including 28 years in the Army Reserves)

b. Being a rancher in Texas

c. Studying chemical engineering at Bucknell

“The class is an eclectic mix of material, which I consider a strength. We read fiction, autobiography, philosophy, history and criticism. We look at images from the past and present. And we do so through an intersectional framework, which means we always consider sex and sexuality in conjunction with gender, race, class and other identity vectors. Each week, students write short responses to the material we read and discuss, and they share their thoughts with the class. The next week, the new responses must incorporate the new readings and include references to students’ analyses from the week before. In this manner, we are producing a shared class text. We are all engaged in the process of discovery and knowledge creation. It’s super cool!

The 6-foot-3-inch forward from Paoli, Pa., was competing in a high school all-star game when she stole the ball and broke for the other team’s basket. En route, she stepped on another player’s foot, which wrenched her ankle and caused an audible “pop” in her left knee.

“My knee felt loose, and I didn’t have control over my motor movements,” Mack recalls. “I remember lying on the gym floor staring at the ceiling. The first thing I said was, ‘I just tore my ACL.’ ”

The anterior cruciate ligament helps stabilize the knee joint. Recovery is a months-long process that forced Mack to sit out her first season. She said rehabilitation was an “extremely difficult” time, during which she occasionally worried whether her skills would return.

Lynn Pierson knows volunteers. As assistant director of community service in the Office of Civic Engagement, she and her team annually manage hundreds of volunteers and their projects here and abroad. She matches volunteers with projects that stoke their enthusiasm, and matches organizations’ needs to the volunteers who can fulfill them. She’s responsible for keeping things on track so that even when chaos reigns, her volunteers are working toward their shared goal.

Lynn Pierson knows volunteers. As assistant director of community service in the Office of Civic Engagement, she and her team annually manage hundreds of volunteers and their projects here and abroad. She matches volunteers with projects that stoke their enthusiasm, and matches organizations’ needs to the volunteers who can fulfill them. She’s responsible for keeping things on track so that even when chaos reigns, her volunteers are working toward their shared goal.

nstead of “good morning,” a villager greets you by saying, “bright suns.” The nearest bathroom? That query gets you a blank stare, but you’re told the closest “refresher” is just past the Toydarian Toymaker shop. And — wait a parsec — is that person drinking blue milk?

Clearly, you stepped out of the traditional theme-park experience and into a galaxy far, far away.

At Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, the new themed land at Disneyland Resort and Walt Disney World Resort, every element, from the life-size Millennium Falcon to the droid tread tracks in the ground, is crafted with a Jedi Master’s attention to detail.

Challenges

with

Photograph by Saroyan Humphrey

Challenges

with

Photograph by Saroyan Humphrey

This is a story about rough waters.

Take Nothing for Granted

For Amal Kabalan, hope can be found in her resilient students. Kelly Knox is inspired by the legacy of the late English Professor Carmen Gillespie. Joe Tranquillo celebrates the value of taking a timeout rather than living in perpetual “run” mode. Yasameen Mohammadi ’20 rediscovers hope after family tragedy. For Chet’la Sebree, hope resides in careful use of language. Nikki Young pins her hopes on a more inclusive, equitable and diverse Bucknell. Matt Bailey looks to analytics as a solution to time-sapping problems. And John Hunter urges us to think in new ways. I hope you enjoy their essays on the following pages.

A final word: What does hope mean to you as we move into 2020? Please share your thoughts at bmagazine@bucknell.edu or on @BucknellU social media channels.

— Sherri Kimmel, editor

For Amal Kabalan, hope can be found in her resilient students. Kelly Knox is inspired by the legacy of the late English Professor Carmen Gillespie. Joe Tranquillo celebrates the value of taking a timeout rather than living in perpetual “run” mode. Yasameen Mohammadi ’20 rediscovers hope after family tragedy. For Chet’la Sebree, hope resides in careful use of language. Nikki Young pins her hopes on a more inclusive, equitable and diverse Bucknell. Matt Bailey looks to analytics as a solution to time-sapping problems. And John Hunter urges us to think in new ways. I hope you enjoy their essays on the following pages.

A final word: What does hope mean to you as we move into 2020? Please share your thoughts at bmagazine@bucknell.edu or on @BucknellU social media

channels.

— Sherri Kimmel, editor

At the beginning of every semester, I feel like a child in front of a Christmas tree, ready to unwrap new stories. I feel very honored and humbled when students talk to me about their passions, their struggles, what makes them tear up and what inspires them to jump for joy. Whether driven by an urge to do better because their parents worked hard to send them to Bucknell, or an eagerness to find meaning in a new life after escaping a war zone, the stories my students share inspire me.

In different industries and contexts all over the country, there are impassioned and caring people besieged daily by quotidian tasks. An example from my recent research project with Professor Lucas Waddell, mathematics, involves a newly appointed administrator of a school providing full-day, one-on-one tutoring for autistic students.

Each day the administrator struggles to match each of his 100 autistic students with an appropriate tutor for every hour of the subsequent day. This task is further complicated by the students’ and tutors’ availability, and the need to match a tutor’s qualifications to a particular student’s needs. The administrator spent 10 frustrating hours per day juggling the creation of the next day’s schedule, and in real time, correcting the errors in the current day’s schedule.

I immediately flashed to some of the amazing students with whom I’ve had the privilege to work — those with ambition to improve human and environmental conditions are a continuous source of hope to me, so I was ready to write.

Then I heard the news. My dear friend and colleague, Professor of English Carmen Gillespie, passed away suddenly on Aug. 30. My heart broke. People far beyond the scope of campus who knew Carmen were devastated, with people reaching out to me and other friends of hers through social media, emails and phone calls, expressing shock and grief from all parts of the country and globe. Hope had dissipated, and I no longer had anything to say. What could I possibly have to contribute about hope in the shadow of such sadness?

Change. Repeat.

Change. Repeat.

Sometimes writers presenting work are defensive of the strategies, techniques and devices they’ve used — hostile to the idea of revision. From this was born the workshop in which the person receiving criticism is not invited to speak until the end. Sometimes people offering feedback are at a loss for how to thoughtfully comment on the presented work because it’s either too polished or too obtuse. This can lead to negligible comments that result in shallow revisions or a request for a better explanation of the point of the piece, which can either lead to resistance or acquiescence (and, hopefully, major revision). When everything aligns as it should, everyone works together in collaborative, generous ways.

to Change

to Change

This is why I know that hope is a necessary component of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) work. As a faculty member and administrator, hope is my constant companion. It helps me as I work with colleagues and students to build knowledge, develop skills, offer support, produce ideas and co-create learning and working environments for a community in which each person feels and lives with a sense of belonging. My courses as well as the DEI efforts at Bucknell are about creating a context, community and capacity in which each person can thrive. The work is about place-making and social transformation. It is about shifting the perspectives about inclusion and equity. Even more, it is about building on the vulnerability of our desires and knowing that the Bucknell for which we hope may be something not yet imagined.

Radical Change

The consequences of realizing all of this is that our lives will have to change radically — it is no longer a question of looking for “growth” or “innovation” or an improved version of what already exists. We need to be willing to re-examine and to radically change some of the most fundamental aspects of American life: Can we imagine being a nation in which owning a car is not a necessity for middle-class life? After two centuries of industrial civilization telling us that we could always master our environment, can we learn to care for it? Or subordinate our desires to its needs?

We humans have come a long way from these humble beginnings. We can endure some pain for the promise of better times, we can reflect on experiences and learn from them, and we can adapt our actions based on advice and observing others. But we still run when we are certain and tumble when faced with uncertainty.

Run mode is measurable and observable by others. We get rewarded for running. Set a goal, take actions, show off your results and move on to the next goal. In my case, being a professor has been all about run mode — long term to get to this point in my career, and short term as I switch between the various roles I play. But there’s a catch to living in run mode — it is all too easy to become blinded by our goals, or even worse, accept someone else’s goals as our own. Sometimes sorting all of this out seems hopeless.

As a middle-schooler in my war-torn country, Afghanistan, I was strangely hopeful – not only for me but for my country – that the bomb blasts and the war would stop one day. When everyone else said it was impossible, I still thought Afghanistan was my future and that I would never have to leave it for good. I saw myself as part of the solution; therefore, I read books, discussed issues and asked questions, remained intellectually curious, and actively fought for gender equality and human rights. My activism and academic record earned me a scholarship to transfer to an international high school in Minnesota and later to Blair Academy in New Jersey. There, I found people who believed in my hopes and helped me get a first-class education so I could make myself and my country better. Life was great.

But in summer 2013, when I returned to Afghanistan to spend my school break with my family, I lost a dear cousin to a bomb blast. He was only a couple of years younger, we had spent our childhoods together, and he too hoped for a better tomorrow. I could not believe that he was taken from us so brutally. I hated that we were all so helpless. For the first time in my life, my hope for a better tomorrow had dried up with every tear that fell from my eyes. I was depressed and lost all confidence that I could change the world.

OUT

Photograph by Derek Lapsley

OUT

Photograph by Derek Lapsley

er life was suddenly interrupted when the U.S. government plucked her out of her world and sent her to a desert relocation camp. Two years later, in a twist of nearly equal proportion, her life resumed — at Bucknell University. Now age 93, she’s the only known Bucknellian alive to share her story of being detained in a Japanese American prison camp during World War II.

In the 1940s, Sachiye “Sachi” Mizuki Kuwamoto ’48 was an all-American girl living in California’s lush Central Valley. Her parents had been born in Hiroshima, Japan, but now were hard-working grape farmers in Sanger, a town known for the General Sherman, a 267-plus-foot sequoia so majestic that a 1926 act of Congress designated it a National Shrine. She was a serious student, expected to follow the customary plan of her day: graduate from high school, attend a local college, then marry.

Dorothy, who died in 2010, told Midori about her life in the camps and at Bucknell. Whereas Sachiye’s family traveled directly to the Colorado River Relocation Center in Poston when ordered to leave their home, the Sakasegawas “were first removed to the Salinas Rodeo grounds and put in horse stalls,” Midori recounts. “It was kind of like, ‘Wait a minute. We’re staying here?’ ”

Midori says the experience left the Sakasegawas conflicted as Americans. “They wanted to show that they were good, loyal American citizens — be grateful and positive by enduring what was difficult, which is a very Japanese trait.” When she became a teen, Midori pressed her mother about her reaction to incarceration. “She said that you understood that something was not right, but you had to learn to put a good face on it.”

After her mother spent her junior and senior years of high school in the Poston camp, “the opportunity to come to Bucknell was huge for her,” says Midori.

THE FOUR C’S

So what happened? I believe we can encapsulate the enrollment challenges in higher education in four words: cost, confidence, community and continuity.

Submit your own photos to Bucknell Magazine by contacting your class reporter or emailing classnotes@bucknell.edu

After graduating from Bucknell in 1968, my first 20 years included marriage, children and working as a children’s-music educator. But in midlife, I began paying more attention to a long-deferred call to ordained ministry. I tested this call by taking a unit of chaplaincy training at Williamsport Hospital. While learning how to provide pastoral care to folks with respiratory illnesses, I learned much about myself and my gifts for ministry. The experiential education I received in those seven months emboldened me to take a bigger plunge. In 1988, as a midlife, single mother of four, I headed off to Princeton Theological Seminary for a master of divinity degree. When I told the admissions officer that my Bucknell major had been history, he told me that a history major was excellent preparation for theological studies. Who knew?

In the 20 years that followed seminary, I put that academic and spiritual formation to use, first as a parish pastor, then as a geriatric chaplain and, finally, as a hospice chaplain. Now, in semi-retirement, I minister part time as a spiritual director and retreat leader. I am also a newly published author of a book of 52 meditations for older adults.

Sculptor Lynn Duryea ’69 knows commercial success — for years, Tiffany & Co. sold her hand-thrown vessels in its iconic Manhattan store. But success didn’t come easily: Along the way, she briefly worked in a sardine factory, endured the craft-show circuit and came to accept the unknown.

“To be an artist, you must be comfortable living with uncertainty,” she says. “I’m fortunate. There are compromises I’ve made to be an artist, but I never had a 9-to-5 job that made me miserable.”

Geography, as much as any grand plan, dictated Duryea’s trajectory. After majoring in history at Bucknell, Duryea started a master’s in art history and took pottery classes. Eventually, she abandoned graduate school and a starter job at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to settle on Maine’s Deer Isle, where she studied at Haystack School of Craft. She embraced the creative community, developed galleries and partnerships, exhibited internationally and won prestigious awards, taught workshops and volunteered.

“It was the first time I was around people who were living their lives creatively,” she says. “We made a family, and many of us are still there. It’s home in a really deep way.”

Whether dealing with primates or Army privates, Bernadette Pergrin Marriott ’70 has spent most of her adult life studying how different foods and their nutritional components affect her research subjects’ health.

Her studies took her to the jungles of Nepal and Panama, where she researched how baby monkeys learn what to eat, and to the National Academy of Medicine, where she recently chaired a workshop titled Understanding and Overcoming the Challenge of Obesity and Overweight in the Armed Forces.

Advising the military on how to keep soldiers fit — educating about key nutrients and the potential perils of consuming body-building supplements with undisclosed composition — is a vital mission for Marriott, professor emerita in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology and the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina.

When Phil Lohr ’81 graduated from Bucknell with degrees in mathematics and computer science, the chances he’d someday become a brewmaster were quite slim. Yet 38 years later, Lohr is a brewer and co-owner of Hops on the Hill, Connecticut’s only farm-to-glass brewery.

“It certainly has been an interesting journey,” Lohr says of the path that led him from Lewisburg to his small farm in South Glastonbury, Conn. While working in computer science, Lohr began hobby brewing.

“Home brewing, in the shuffle of a corporate life and raising four children, was something I did maybe a couple of times per year,” Lohr explains. “Not until the last five years or so did this vision really come alive.”

As his career transitioned to organizational development and consulting for major corporations such as Aetna, General Electric and Merck, Lohr’s passion for brewing was reinvigorated by a 2008 trip to Bavaria, Germany, where he learned to brew German-style lagers. “It’s a very old beer culture there,” he says. “The German-style beer and beer gardens are part of the lifestyle.”

Public service has been a core value for Teresita Batayola M’88 since her studies in urban administration at Bucknell. The president and CEO of Seattle-based International Community Health Services recently was named one of the most influential Filipina women in the world by the Filipina Women’s Network.

Bucknell had a brief graduate partnership with the National Urban Fellows, a program for mid-career professionals who aspire to public-sector leadership. The combination of intense seminars and a placement as an assistant to a federal department secretary refined and focused my desire to be in public service.

Seminars on economics with Professor Steve Stamos drove home the impact of macro and micro financial policies and actions on businesses, governments, communities, families and individuals.

Genetic counselor Laura Rittmeyer Jenkins ’88 explains that when calling a patient with a new genetic diagnosis, she is quick to caution, “Do not Google this,” adding, “The internet loves the worst-case scenario, right?” To counter online information that can be overwhelming and frightening, Jenkins steers patients away from the uncurated information that can be found on the internet and provides specific online resources to help patients learn about and adjust to a new diagnosis.

Jenkins first discovered the relatively new field of genetic counseling at the wedding of Stefanie Lin ’88, P’19 during a conversation with Lin’s sister, a geneticist. Jenkins, who majored in psychology and English, soon found herself pursuing an M.S. in genetic counseling at the University of Pittsburgh. Since 2015, she has worked at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and is an adjunct instructor in human genetics at the University of Pittsburgh.

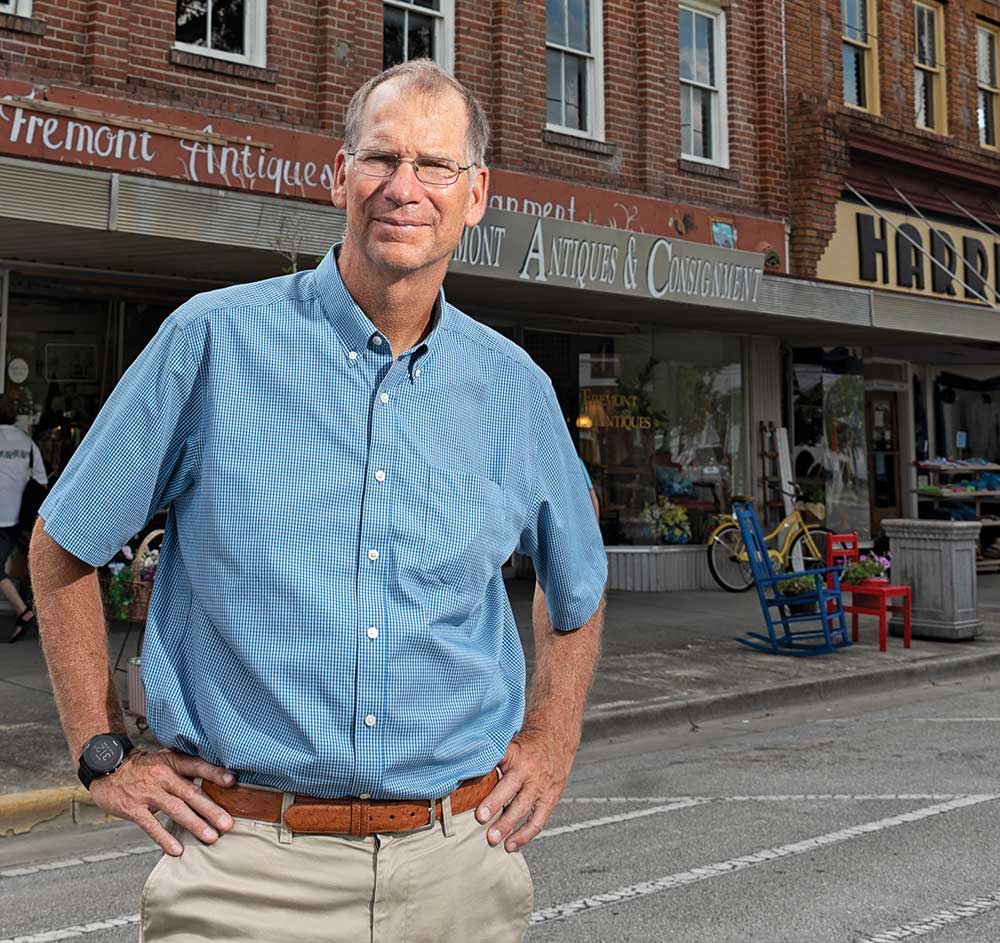

by Matt Zencey

When Richard Johnson ’84 was in fifth grade, he would spend his allowance on toothpicks, dip them in cinnamon oil and sell them for five cents each. By seventh grade, he was buying cases of Life Savers candy and selling individual rolls to his classmates. It was an early sign that he might do well in the business world — and he certainly did. In the late 1990s, the Bucknell political science major founded HotJobs, an early internet job search and recruiting site. It proved to be so hot that Yahoo bought the business for more than $400 million in 2002.

Selling to Yahoo made possible what Johnson calls “Life 2.0,” a long interlude when he focused on his family and sharing his marketing and management expertise with several nonprofit groups. Since 2005, he has lived along the southern coast of North Carolina, where he recently founded a community group to promote better stewardship of Masonboro Island, an undeveloped nature preserve across the water from his home that was being trashed by rowdy visitors.

“One of the things I really value about a liberal arts education is learning how to think broadly,” Katie Pfeifer ’05 says. “Under-standing how we interact with the world and how we come together and work — or don’t work — really appealed to me,” says Pfeifer, who majored in economics and international relations.

This liberal arts lens through which Pfeifer views the world led her to a career in the nonprofit sector and to Volunteer New York!, one of the oldest volunteer connector organizations in the world, now in its 71st year. Pfeifer, as the director of programs and evaluation, is at the heart of the organization, overseeing its programmatic success. The Readiness thru Integrated Service Engagement (RISE) program is one she helped start and of which she’s most proud. RISE was created to address an increase in the number of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities looking to volunteer. RISE participants build job and community skills as they assist nonprofits.

The RISE program “really helped us clarify something we all felt,” Pfeifer says. “Everyone can make an impact, and everyone can make a difference. It’s really about trying to find the right fit for each person so they can shine.”

As a dentist on land, providing a patient with a partial denture is no big deal. When you’re out to sea on a Nimitz class aircraft carrier, however, you’ve got to get a bit creative, observes Josephine “Joy” Vargas ’13. “It’s challenging, because we have to make do with materials we have on hand, but we get it done,” she says.

A lieutenant in the U.S. Navy Dental Corps, Vargas is deployed in the Middle East aboard the 5th Fleet’s USS Abraham Lincoln. She leads a team of three dentists, an oral surgeon and 14 corpsmen treating more than 5,000 sailors.

Life aboard ship can be stressful, she concedes. “I live a mixture of dentistry and military life,” she explains. “I live in my workplace, my days are long, and we’re deployed, so the stress level in our environment is constant.”

Jack Reyer, Aug. 1, Hermitage, Pa.

Esther Herrington Wheeler, July 18, Pittsford, N.Y.

Helen Lupold

Deffenbaugh, Sept. 22, Muncy, Pa.

Paul Lenchuk, Aug. 15, Winter Park, Fla.

Jay Maisel, Aug. 30, Sarasota, Fla.

Alden Dalzell, July 3, The Plains, Ohio

Nancy Bishop Douglas, Sept. 9, Urbandale, Iowa

Rita Scholato Paulosky P’75, Feb. 13, Minersville, Pa.

Emilie “Lee” Luke Schmauch P’76, Sept. 9, Topton, Pa.

Rose Robyns Coelho, May 13, 2018, Vaucresson, France

Joseph Kishel P’73, P’85, July 25, Exeter, Pa.

Arthur Troast P’83, July 24, Jupiter, Fla.

Nigel Robinson ’14 is an agent of change who knows the value of playing the long game.

After Bucknell, Robinson worked for the Steppingstone Foundation in Boston, helping underserved children prepare for college success. But he also wanted to use his international relations major. “I wanted to expand my reach, to touch more lives and see more of the world,” he says.

Robinson won a fellowship in 2018 from the Charles B. Rangel International Affairs Program, named for the former Democratic congressman from New York. The U.S. State Department program was founded in 2002 to promote diversity and excellence in the corps of young diplomats.

Bucknell and the Holocaust

Bucknell and the Holocaust

What was your best student job?

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK TO SUBMIT YOUR ANSWER

With a song in their hearts — and a lump in their throats — 31 alumni shared the Rooke Chapel stage with 17 current students to sing the plaintive “Hallelujah” on Nov. 2.

Written by Leonard Cohen and arranged by the group in its early years, “Hallelujah” has been the closing number for most Beyond Unison performances. So it was a natural choice for the conclusion of the acapella group’s 15th anniversary concert.

“As I look back over 15 years, I’m amazed at how the group has grown,” says Jon Backhaus ’07, who with Laura Householder McFalls ’08 and Anna Riker Mulligan ’08 founded Beyond Unison.

“Leading up to the weekend concert, the group started an email chain to share memories about what Beyond Unison meant to each person,” says Backhaus. “What struck me most was the sense of belonging — the sense of family — that has persisted through the years. In talking to alumni after the concert, I realized how the group has touched so many of us.”

Alumni and students each sang five songs, including Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida” and “Here Comes the Sun” by the Beatles. “I was amazed at how good the songs sounded,” says Max Code ’21, vice president of Beyond Unison. “It sounded like a release from the last spring concert.”

Print is lovely, print is fine. It will be with us for a long, long time.

Well, that’s what we think here at Bucknell Magazine. But there’s also an advantage to having a digital replica of the print magazine to carry with you everywhere you go. And that’s why, starting with our Fall 2019 issue, we’re now offering a digital option. We’re only the second school — and the first private — in the nation to adopt this new technology, and we’re hearing good buzz from our readers.

Not only are the aesthetics of the print magazine preserved, but there are no downloads or apps required. Just type magazine.bucknell.edu into your browser, and start reading. This new, portable version of your print magazine works whether you’re using a tablet, a desktop or a smartphone. And our future issues will be archived at the above URL.

All the stories, photos and art are on display in the digital magazine. But one thing is not: Class Notes. And there’s a good reason. We want to protect any information our alumni wish to keep within the Bucknell family. Putting Class Notes into the digital sphere would make it more likely to be widely distributed. If you love the new digital edition and would like to opt out of the print magazine, you can join the list of digital subscribers, and we’ll send Class Notes to you in PDF form when each issue is published.

Drew Hopkins ’20 doesn’t seek the spotlight. The lighting designer for Bucknell’s dance, theatre and music shows says audiences shouldn’t think about the lighting at all. “My whole goal is for them to silently appreciate,” he says. “To say, ‘Wow, everything seemed right.’ ” If the stage is Hopkins’ canvas, the ETC Gio @5 is his paintbrush. The political science and theatre double major from Newtown Square, Pa., can take audiences from a sunlit square to a flashy nightclub with a few taps, keystrokes or twists of a dial. In the shadows, he shines.

Drew Hopkins ’20 doesn’t seek the spotlight. The lighting designer for Bucknell’s dance, theatre and music shows says audiences shouldn’t think about the lighting at all. “My whole goal is for them to silently appreciate,” he says. “To say, ‘Wow, everything seemed right.’ ” If the stage is Hopkins’ canvas, the ETC Gio @5 is his paintbrush. The political science and theatre double major from Newtown Square, Pa., can take audiences from a sunlit square to a flashy nightclub with a few taps, keystrokes or twists of a dial. In the shadows, he shines.