His childhood home, a 16-story iron apartment building on Riverside Drive between 83rd and 84th streets in Manhattan, provides plenty of details to draw from. Babe Ruth lived a few floors above the Blaustein family — Joe; his two older sisters; his father, a Jewish refugee from the early 20th-century pogroms in what is now Ukraine who, Blaustein says, became “New York’s official bankruptcy auctioneer”; and his decorative mother. The latter created quite a stir in Lewisburg during Blaustein’s first year.

He writes, “Archie, our chauffeur, drove my mother up for a visit — the only member of my family to ever do so. Mother wore red, red lipstick, had Theda Bara-style plucked eyebrows, and smoked while walking in the street. I found out later she was the gossip of the town: People thought she was a prostitute.”

Recalling one detail from decades ago leads to another and another. He tells me before recounting an incident from his childhood:

“I remember getting in the elevator with this woman. She was beautifully made up, staggeringly beautiful. And I remember her hair — black hair that curled around, very French. Named Essie. And I remember how she smelled. Wow. In writing the detail of that fragrance [in his autobiography] I realize that impression still lives with me.”

The 1,200-pages-and-counting autobiography Blaustein is writing is chockful of details like those above. On the following pages is an excerpt from his chapter on Bucknell. I hope you relish these palpable descriptions by a Jewish student of the 1940s as much as I did.

— Sherri Kimmel, Editor

arvard’s response to my application was terse:

“Our Jewish quota is filled for 1940; you are accepted for 1941.

“You’re young; we suggest you attend prep school then transfer.”

In retrospect, I wonder how the hell they knew I was Jewish. If I changed my name to O’Shaughnessy, would I have been accepted? Was I surprised? Nah … hardly blinked.

But not wanting to stay home contemplating my navel or sell magazine subscriptions in Brooklyn or, worse, work for my dad like everyone else in the family, I went to the American School Association at Rockefeller Center for advice. Exeter? Andover? Horace Mann with old friend Mort? Their comment was that after high school at City College, a prep school would be going backwards. “Attend a small ‘Ivy League’ university and then transfer,” they said.

They recommended Bucknell, which they listed among the top schools academically in the country. Without even checking it out, I applied, and although fall classes had started, Bucknell reviewed my academic record and said I should come for tests. They either didn’t have a “Jewish quota” or they had room for one smart-ass Jewish boy.

On the all-night train trip to Lewisburg, I was accompanied by my brother-in-law, Frank. Frank slept. I could not. To this day I can smell the musty odor and feel the hardness of the worn, green-patterned, cushioned seats. In the dim yellow light, I could see the countryside flashing by as I stared through a smeared window. I arrived and noted the contrast — clean, brisk air, bright early-morning sun. Walking the silent cobblestone streets of the town to campus, the red-brick buildings on the hill above created a fairytale dreamscape. I smelled the heady and heavenly perfume of freshly mowed grass, richly green, on the expansive quad. Yes! This is where I wanted to learn, live. I felt reborn. Despite not having slept, I felt the tests, which lasted all day, were fun — like puzzles. When finished, I was called into the administrative office and told, “We are accepting you despite being three weeks late. If you get anything but A’s, you’ll not be working to your potential. Welcome to Bucknell!”

Half-starved, suddenly sleepy, Frank and I went to eat at the hotel — the only one in town — by the Susquehanna River, but I was so exhausted I couldn’t eat. We took the night train back home. This time I slept. Funny how minutely I can recall that first train ride, but can’t recall the second and third or goodbyes from home, packing or anything other than my parents ignoring the whole event. I returned alone, the third trip in three days, and, except for a week’s leave from the Navy after my ship was hit four years later in World War II, I would never live at home again.

Since I’d missed freshman orientation, I was a bit lost but not in the least homesick. Quite the contrary: My spirits soared. I felt free from family, free from the city. I fell in love with the countryside, the wide Susquehanna River, the 19th-century churches and townspeople who said good morning or good afternoon with smiles like they meant it as you passed in the street. The town had only 3,000 people (probably no more than our apartment complex on Riverside Drive in Manhattan). But the real revelation was that, for the first time in my life, learning was exciting, each class a discovery. Professors addressed us as if we were intelligent. I loved it. Between classes or walking the town, I would burst into a run for pure joy. No more honking horns or hordes of people crossing streets. As I write this from the distance of 80 years, I recall that my home — and my role as the good son, the good brother — was a million miles away. Selfishly, I gave my family — mother, father, three sisters, New York, not a second thought.

That first semester, dressed by Brooks Brothers — flannels and tweed jackets, classy, I got all A’s, made the dean’s list. I was somewhat blondish with light eyes, so I was recruited by two of the “hot” fraternities, Phi Gamma Delta and Sigma Chi. Then they discovered Sigma Alpha Mu, the “Jewish house,” also had invited me. Oops. End of Phi Gam. End of Sigma Chi. No explanation.

First the Harvard quota, then this — a double whammy. Of course, I’d heard about antisemitic rumblings in Europe — and knew my father had escaped Russia from the pogroms of 1905 that afflicted his East European ghetto. But this was here, in America. Suddenly, at Bucknell, I was a JEW, although I was religious as a salamander. The ridiculousness of it struck me.

For the first time in my life I was suddenly singled out as Jewish. What did it mean? Well, food for one thing — not “what” you ate, but “where.” The campus was dominated by the Greek system, and the frat houses and sororities had their own dining rooms. Sigma Alpha Mu, called “Sammy,” was one of about 20 other fraternities and comprised about 50 men with “Jewish” names. Like the other men on campus, they ate at the frat house. Not wanting to eat in solitude, I eventually became a “Sammy” and took all my meals at the big, sprawling, two-story red-brick colonial down the steep hill into town. In winter, I’d ski down. However, I refused to move in and stayed in the dorms, on campus.

The frat brothers and I became friends, so why didn’t I move in? The house was freaking noisy, for one thing. I preferred to study alone in the library, across the quad from my dorm room, where it was quiet. Another reason is that I hated the idea of putting myself in a category. I now recognize that throughout my life I’ve always liked being a loner.

By the way, the food at the frat house was indistinguishable from food anywhere. All the brothers were secular; not one wore a yarmulke. Nor did anyone observe any holidays — we were really no different than the Phi Gams or the Sigma Chis, except for our names.

Still, despite the new understandings that dawned on me daily, I remained in heaven at Bucknell. Then suddenly, about three months after my arrival, I felt as if someone had smacked me over the head with a two-by-four. Why? I was rejected — by a girl! How dare she!

It happened like this: She — lithe, slender and tall with a ski-jump-shaped nose — had accepted a date to go to a movie. When I went to pick her up, I saw that something was wrong. She stood in the doorway, eyes moist.

“I … I can’t go out with you,” she said. “My sorority said the Sammies pledged you. We don’t date Sammies.”

I stared at her, not understanding. Then I got it. Sammies were Jews. My eyes narrowed. I turned. Walked away. Said nothing.

Rejection was new in my life, and rather than risk it further, I asked no one else for a date that year. However, early in my sophomore year, I saw this smashing girl, got over the silliness and asked her out, telling her up front that when she realized I was a Sammie she’d probably reject me. She laughed, and just like that, I fell in love. She was a year behind me in school, at Bucknell on a scholarship, pledged by the same sorority as the girl the prior year and given the same instruction: Don’t date Sammies. If that’s the way they thought, she wouldn’t join them, she told me. It was their loss, as Barbara was a statewide scholarship honor student.

Since she lived in town with her parents, I met her mother on our first date. Her father, a tall, dignified, handsome and gentle man, was an engineer for the state and hardly ever home. But her mother became part of the package that so enthralled me. They had what seemed to me a vast knowledge of world literature and were so interested in and informed about what was happening outside of the confines of a small town in rural Pennsylvania. Incidentally, to my knowledge there was not a single Jewish family in that town, and I doubt any in several of the outlying communities.

Barbara said she and her mother never missed a night reading together. My first love letter and gift from Barbara included a Shakespeare volume so I could read a particular sonnet she’d flagged, describing her feelings. It’s still in my bookcase, two marriages and almost 80 years later.

At the frat house there was a lot of card playing and gambling. I wasn’t interested. Since there was only one movie house in town, 13 churches and few dates, the Sammies spent the rest of their time studying, obtaining the best grade average on campus. On big prom weekends, we imported dates from home.

Later, I became co-prior, or president, of the house (“co”-prior because I still lived on campus). I decided to use my position to take on some of the prejudice we’d experienced. Mort Silberman ’43 and I arranged a meeting with President Arnaud C. Marts to discuss fraternity-sorority prejudice. A meeting of fraternity and sorority presidents was called. The problem was discussed and, of course, denied. The only thing we accomplished was to make me, Mort and the Sammies pains in the butt. Nothing changed.

So there were plenty of downsides to being Jewish at Bucknell in the ’40s. But the upside made up for it tenfold. I really did fall in love that first year — with the town, the rolling countryside, the wide Susquehanna River, but mostly just with being in college in the first place. In each class, a world I never knew existed turned me on in ways no date could have. Inspired and inspiring teachers widened my eyes with knowledge and an inquisitive attitude that has stayed with me for the following 80 years. Bucknell had a reputation for scholarship then, as it still does, partly because of the small number of students in each class. We didn’t get TAs; we got the real deal, like Philosophy Professor William Allison Shimer, editor of The American Scholar, or Philip Harriman, a famous psychologist and specialist on hypnotism. I’ve often thought that if my kids could get one inspirational teacher in all their schooling, they would be lucky. I had several.

Another one was Mildred Martin, whom I met in her required, two-semester overview of World Lit. She was in her mid-50s, I’d guess, tall, slender, ungainly, with light-brown, frizzy, unkempt hair; she wore wire-rimmed glasses and not a dab of makeup. But as she read amazing passages or recited whole sequences by heart, she became the most inspiring person I had ever known. Her face lit up, and she would smile with joy as she read Milton, Chaucer, Pope. Her enthusiasm was catching. I discovered words to express my own inchoate feelings, such as “… these violent delights have violent ends / and in their triumph die, like fire and powder / which as they kiss, consume. …” from Romeo and Juliet.

Miss Martin became a friend and mentor. Her inspiration is perhaps why I started teaching as an adjunct, which lasted 63 years, giving me the pleasure of seeing students catch fire, making their own discoveries. In that second semester, she introduced some contemporary authors. After our final class, she asked me to stay. She wanted to tell me there were three novels she had not assigned: “Read them!” They’re still in my library: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, James Joyce’s Ulysses and Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. In 1940 and 1941, they were important recent works — and still are. My world was exploding, and I am forever in debt to that lovely woman and her enthusiastic love of lit. She changed my life.

And then my world exploded again, as it did for all of us, but not in a good way this time. On Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked. I was 18, midway through my sophomore year. I remember where I was: in the old fraternity house common room with all my frat brothers, huddled around the radio listening to President Roosevelt’s address to the nation: the “day of infamy” speech. Several who listened with me would not survive the next three and a half years. That radio broadcast changed everything — my life and all my friends’ lives — and wound up disrupting my education and my romance with Barbara.

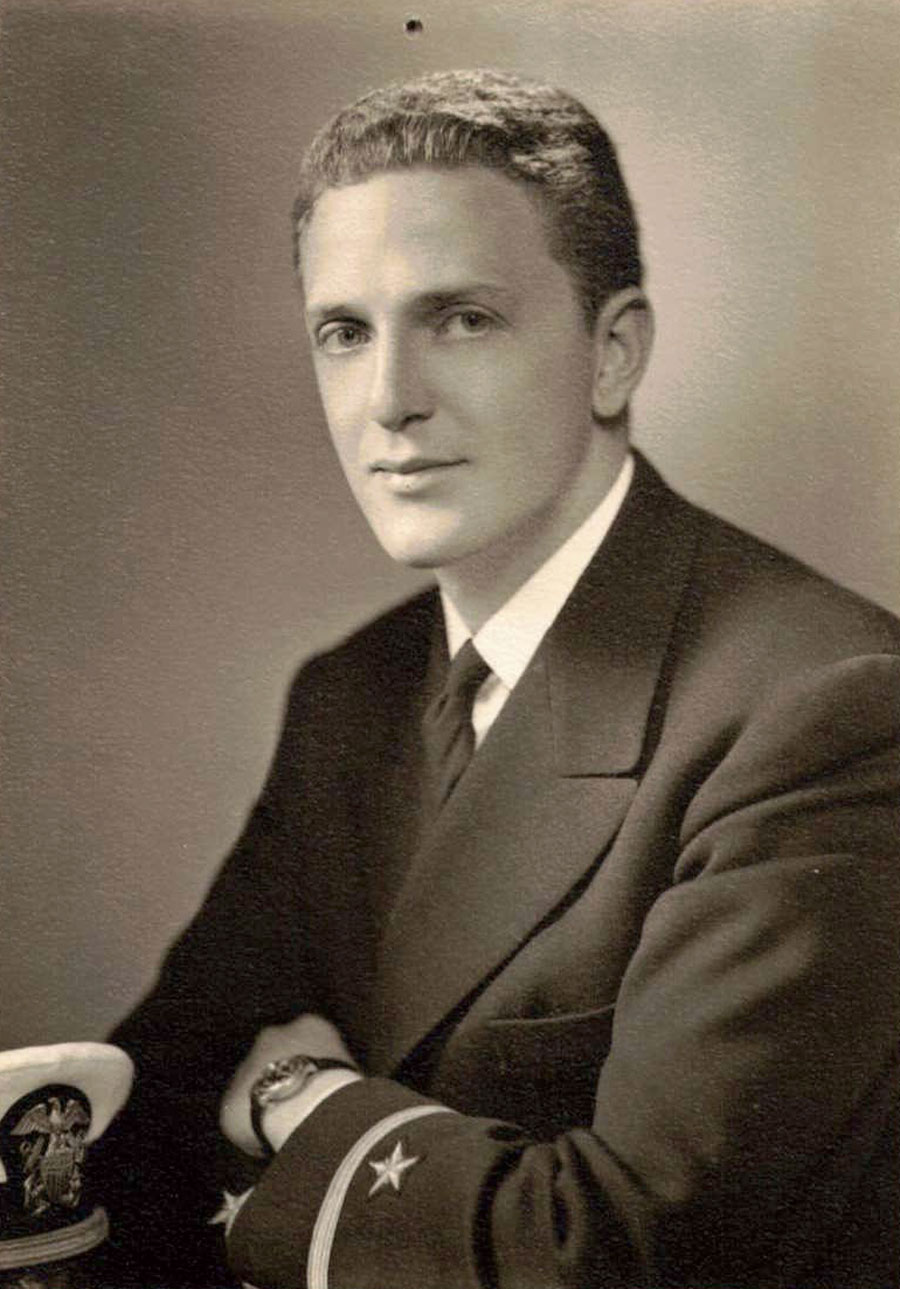

A few months later, I was still 18, and although the draft was to start at age 21, I enlisted in the Navy, not entirely based on patriotism. Perhaps I thought I looked good in blue, or maybe dying on a ship or drowning at sea seemed less messy than slogging through mud in Europe or a jungle in the Pacific. When a Navy recruiter came to Bucknell, I joined. I didn’t ask or tell my parents — had not given them a thought — but when I did tell them, they were grim. I spent the next four-plus years — until June 1946 — in the Navy, coincidentally being assigned to Bucknell’s Navy V-12 program before heading out for boot camp [Bucknell was one of 112 college and universities selected throughout the country to offer an eight-month officer-training course].

I spent the first two years of the war in V-12, midshipman and Counter Intelligence Corps training before assignment on the USS Black (Destroyer 666) in the South Pacific, where I saw ferocious combat during the Battle of Leyte, followed by seven months dodging kamikaze planes.

A year after the war’s end, I finished my requirements at Bucknell and married, not Barbara but Jane, an MFA student at UCLA I’d met after my discharge from the Navy. I graduated cum laude, valedictorian. My undergrad college career was over.