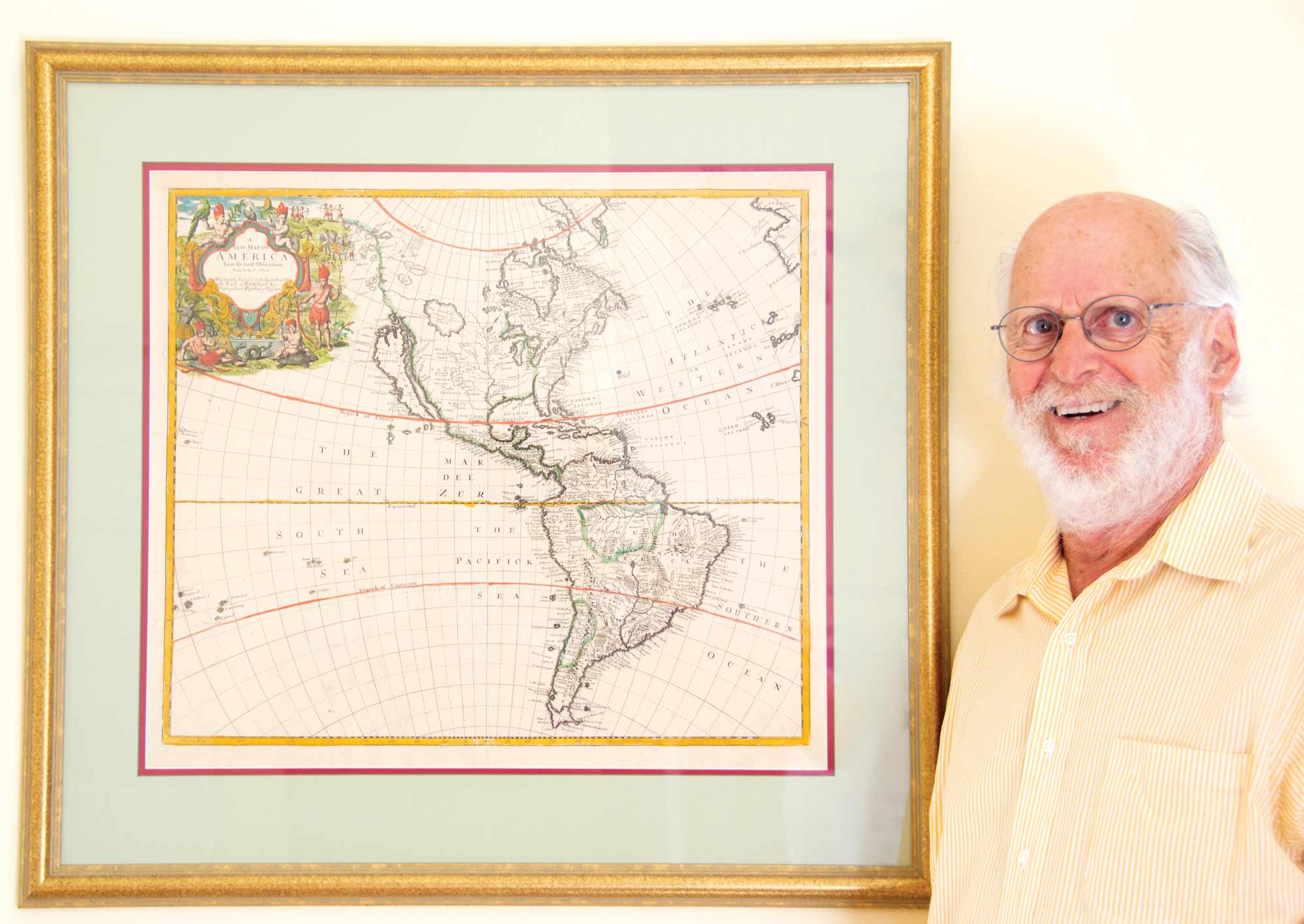

teven Horowitz ’62’s fascination with maps began in the front seat of his father’s car. Growing up in the 1950s, the New York City native often sat up front on long drives through the mountains while vacationing in the Catskills — his parents on either side of him, a roadmap on his lap.

“I was amazed by how decorative and informative these historical maps were,” says Horowitz, a retired neurologist now residing in Maine. “When I walked out of the store, I had this epiphany that I was going to start acquiring them.”

What began as a childhood interest has since grown into a collection of more than 100 historical maps, some dating as far back as the 16th century. Last fall, Horowitz gifted 33 of them to Bucknell for use in history and geography classes.

“I was very fortunate to take all kinds of courses at Bucknell that expanded my view of the world,” says Horowitz, who majored in psychology. “It’s great to be able to give something useful back.”

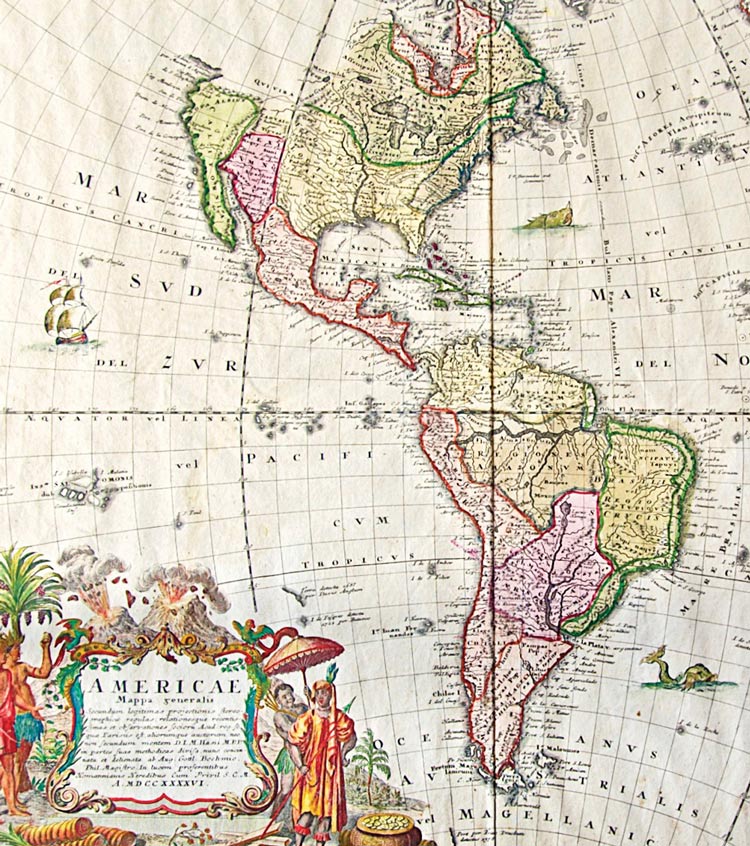

“These imperfections give us an idea of how people thought about the world and how they represented places that were unknown to everyone around them,” he explains. “And we’re not talking about a week, we’re talking about hundreds of years.”

The Bucknell collection consists of maps produced between the late 1500s and mid-1830s. Nearly a third of them are bird’s-eye views of cities across the globe, from Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, to Avignon in the south of France. These maps — several of which originated from an atlas published in 1572 — not only give students a glimpse of how major cities once looked, but also an understanding of what past civilizations valued most.

A 1570s depiction of Cusco, Peru (the former capital of the Inca empire), shows the emperor being carried past the city in an ornately decorated throne-like chair, flanked by spear-wielding guards. Another 16th-century illustration of a Dutch city emphasizes the abbey, which is scaled several times larger than the surrounding homes and other official buildings.

“It’s more than a map when you really look at it — it’s a representation of what life, politics, religion and culture were like during those times,” Horowitz says. “From that perspective, I hope these kinds of documents will be of great value to current students.”

Bremer got involved with the catalog through Professor Claire Campbell, history, who launched the project in collaboration with Bucknell’s Ellen Clarke Bertrand Library.

“As someone who likes to study visuals, I’ve always been interested in maps as ways to depict information,” says Bremer, who’s pursuing a double major in history and English — film/media studies. “This project has helped me develop a deeper appreciation for the history of mapmaking, especially the artistry that went into it.”

It’s also given the New Jersey native an opportunity to blend the skills he’s honing in his film and history courses. In writing descriptions for the website, Bremer says he likes to look at the maps like frames in a film, with the cartographer serving as director.

“Every illustration that’s included in the frame says something about the creator and audience,” he explains. “It’s been amazing to learn so much about these different time periods that way.”

“There were so many faculty in different departments — from philosophy and psychology to religion — that gave me opportunities to be intellectually inquisitive,” says Horowitz, who continues to teach part time at Tufts University. “I wanted to give back to the small liberal arts school where I was able to take advantage of such a special educational experience.”