BY WAY OF BUCKNELL

BY WAY OF BUCKNELL

On October 10, 2024, the aurora borealis illuminated the skies above Bertrand Library with a magical glow.

photograph by emily paine

If you would like a reprint of this photo, please fill out the form at go.bucknell.edu/PhotoOffer. We will send you a complimentary 8×10 print.

On October 10, 2024, the aurora borealis illuminated the skies above Bertrand Library with a magical glow.

photograph by emily paine

If you would like a reprint of this photo, please fill out the form at go.bucknell.edu/PhotoOffer. We will send you a complimentary 8×10 print.

Pathways

photograph by emily paine

That changed after she met Megan Leavy, a Bucknell chemical engineering academic assistant who raises dogs for Susquehanna Service Dogs (SSD). Inspired by Leavy’s impactful work, Feld felt compelled to contribute while still honoring her academic and athletic commitments.

She founded the SSD Club at Bucknell and became certified to raise service dogs in training. Under her leadership, the club trains puppies to assist people who need support. This year, Feld and three other students are sharing the responsibility of raising two Labrador retrievers on campus. The brothers, SSD Douglas (pictured) and SSD Martin, are learning to navigate crowded places, retrieve dropped items and turn lights on and off.

“I picked my major because I love helping people,” Feld says. “Training service dogs is an extension of that. SSD assistance dogs give people the confidence to live more independently — they really change lives.”

Table of Contents

Volume 18, Issue 2

Heather Johns P’27

EDITOR

Katie Neitz

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Barbara Wise

DESIGNERS

Erin Benner

Ashley M. Freeby ’15

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

Emily Paine

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Matt Jones

Heidi Hormel

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Kim Faulk

Contributors

Dave Block, Sarah Downey ’25, Shana Ebright, Mike Ferlazzo, James T. Giffen, Matt Hughes, Brad Tufts, Christina Masciere Wallace P’22, Kate Williard

Website

bucknell.edu/bmagazine

Contact

bmagazine@bucknell.edu

Class Notes:

classnotes@bucknell.edu

570-577-3611

(ISSN 1044-7563), of which this is volume 18, number 2, is published in winter, spring, summer and fall by Bucknell University, One Dent Drive, Lewisburg, PA 17837. Periodicals Postage paid at Lewisburg, PA, and additional mailing offices.

Permit No. 068-880.

Circulation

49,000

Postmaster

Send all address changes to:

Office of Records

301 Market St., Suite 2

Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837

© 2025 Bucknell University

Conveniences and Consequences

That said, I’m also mindful of the environmental challenges plastic brings, especially single-use plastic and its lasting effects. This issue dives into that dilemma. In “The Plastic Paradox”, Assistant Editor Matt Jones highlights how Bucknell faculty and students are exploring more sustainable plastics. He also spotlights Bucknell alumni rethinking how we use plastic.

As part of Bucknell’s commitment to sustainability and our mission to enhance the reader experience, we’re launching a new digital partnership. Beginning with the summer issue, we’ll be working with eMagazines — a platform used by Sports Illustrated, Time and Fortune — to offer a more engaging digital edition. This will provide an improved reading experience, including a new audio feature that will allow you to listen to stories.

Additionally, we will have a robust online archive to make past issues more accessible, and Class Notes will now be available online for easy desktop viewing.

We are excited about this change and will share more details in the summer issue.

Thank you for being part of our Bucknell Magazine readership as we continue finding new ways to share stories that inform and inspire.

Katie Neitz

Editor / k.neitz@bucknell.edu

Behind the Scenes

Our cover story, “The Plastic Paradox”, features the work of two Bucknellians.

Former environmental correspondent and Boston Globe book critic Robert Braile ’77 writes about plastic’s journey from groundbreaking innovation to global environmental challenge.

Meanwhile, Ashley M. Freeby ’15 brings the story to life. This issue marks Freeby’s debut as a designer for Bucknell Magazine. Since her Bucknell days, she’s earned an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and now serves as the communications director and head designer at the Ox-Bow School of Art & Artists’ Residency in Saugatuck, Mich.

Big Ideas, Big Moments at the Bucknell Forum

Actor and activist George Takei opened the semester’s events on Jan. 28, recounting his childhood experience in a World War II internment camp. On Feb. 18, the series featured Kevin O’Leary, chairman of O’Shares Investments and Beanstox, best known as “Mr. Wonderful” from Shark Tank.

The final event on Feb. 23 was an entrepreneurship roundtable featuring 14-time MLB All-Star Alex Rodriguez, Marc Lore ’93 and Bucknell trustee Jordy Leiser ’06.

Following the roundtable, the trio attended a Bucknell-Army men’s basketball game. There, Rodriguez took a half-court shot to win $10,000 for Owen Garwood ’27. He nailed it, igniting a thunderous celebration (see ‘ray Bucknell).

Enhancing Student Support

“I am excited to collaborate with students, faculty and staff to enhance the programs and services that support students’ overall development,” she says. “I look forward to building on the strong foundations of excellence and student success at Bucknell.”

News Ticker

HIGH RANKS

BEST IN BUSINESS

BUCKNELLIAN LEADS FDA

’burg and Beyond

Lewisburg

Every Saturday, Aiden Cherniske ’27 heads to the Lewisburg Children’s Museum to play with robots. As a volunteer for STEM Saturdays, he introduces young learners to science, technology, engineering and math through robotics activities. Growing up in Kent, Conn., Cherniske discovered his passion for technology through a library STEM program, where he learned about coding and robotics. That experience led him to volunteer with the program in high school. Now, the computer engineering major is paying it forward in Lewisburg.

What He Does

Cherniske aims to grab the attention of children under 10 with interactive robotics demonstrations. His work represents a larger mission of the museum to bridge the gap for rural students who are disadvantaged when it comes to STEM education. Cherniske also helps run a LEGO robotics program for middle schoolers at the Donald Heiter Community Center.

The Impact

“It’s so fun to see the kids’ creativity,” he says. They begin with base projects, such as building a helicopter or carousel, and then they experiment with seeing how fast they can make it turn without breaking. One group even asked how they could make the helicopter ADA-accessible. “Seeing them develop those problem-solving skills is the greatest part,” Cherniske says. “Thinking in that way is so important in STEM.”

What’s Next

Looking ahead, Cherniske hopes to expand robotics programming at the museum and start a robotics club there with assistance from Bucknell’s Center for Community Engaged Leadership, Learning & Research.

— Sarah Downey ’25

’burg and Beyond

Atlanta

In 2023, Terian Williams ’26 turned his platform as a Division I athlete into a force for good by founding the It Takes a Village Family Foundation. Through the nonprofit, Williams organizes Christmas and Father’s Day events in his hometown of Atlanta that provide families with housing assistance, groceries, clothing and other essentials. “I wanted to give back, support underserved communities and bring Atlanta together,” he says.

Williams began his college journey at Stanford University, where he spent two years before transferring to Bucknell in fall 2024. “I chose Bucknell for its close-knit community,” he says. “The football team, especially, feels like a family.” As a defensive back, Williams uses his name, image and likeness (NIL) — the legal right that allows student-athletes to earn income through sponsorships — to fund his foundation. Partnering with over 60 brands, he has secured support to drive his mission.

What He’s Done

Recently, the sociology major partnered with Cheez-It and the Extra Yard for Teachers initiative to donate $10,000 to his former elementary school in honor of his third-grade teacher. “Mr. Hayes was so instrumental in my life,” Williams says. “Being able to give back to the school where I met lifelong friends and formed the foundation of who I am today was amazing.”

What’s Next?

As Williams looks to expand his impact in the Lewisburg area, he has plans to partner with Bison Cares, a Bucknell student-athlete initiative, to co-sponsor charitable events. “When people face tough moments, it’s essential to remind them that positivity and support still exist,” he says.

— Sarah Downey ’25

Fostering Empathy Through Dialogue

The program has proven impactful for Bucknellians like Kathy Graham P’03, P’05, associate vice president of university advancement, who attended a session on post-election civility. “It inspired me to approach family conversations with empathy rather than trying to debate or convince,” she says.

Facilitators report that participants apply circle principles across campus to improve communication.

Graham, for example, integrated circle principles into a workshop for her team to encourage constructive discussions. And Kurt Nelson, director of religious & spiritual life, has used the framework in grief support groups. “For students dealing with loss, these circles create a space to feel understood and supported,” he says.

Celebrating a Milestone

2025 marks 150 years since Edward McKnight Brawley became Bucknell’s first Black graduate. To honor this milestone, the Division of Equity & Inclusive Excellence is organizing a yearlong series of events. Learn more: go.bucknell.edu/blackexcellence

Two Significant Gifts Propel Bucknell’s Financial Aid Initiatives

A new endowment from Bob ’84, P’16 and Sue DeMent Gamgort ’84, P’16 will ensure Bucknell’s ability to meet 100% of demonstrated financial need and eliminate loans for students in the Gamgort Family Gateway Scholars Program. Established in 2023, the program provides financial support and mentorship to first-generation college students.

In the College of Arts & Sciences, the Malesardi Arts & Sciences Scholars — named in gratitude for a generous estate gift from the late Robert Malesardi ’45, P’75, P’79, P’87, G’08 and his wife, Doris Fisher Malesardi — awards merit scholarships to academically high-achieving students.

“These gifts exemplify the transformative power of financial aid,” says Bucknell President John Bravman. “They open doors for talented students who might otherwise be unable to attend Bucknell and strengthen our community with exceptional thinkers who will go on to change the world.”

Call It a Comeback

Call It a Comeback

ucknell men’s soccer capped a stunning turnaround season by defeating Colgate, 3-0, to claim the Patriot League championship before 1,400 fans at Emmitt Field in November. Waldemar Kattrup ’25 and Nick Prime ’25 scored in their final home games, leading the Bison to their highest-scoring match of the year. This is the program’s fifth Patriot League title — and first since 2014. The Bison were one of only two Division I teams to rise from last place in 2023 to a conference title in 2024. “Things happened fast, and it was a tough build, but I’m so happy for our guys,” said head coach Dave Brandt, named the Patriot League Coach of the Year. “For our upperclassmen and especially our seniors to be able to experience something like this is just a joy to see.”

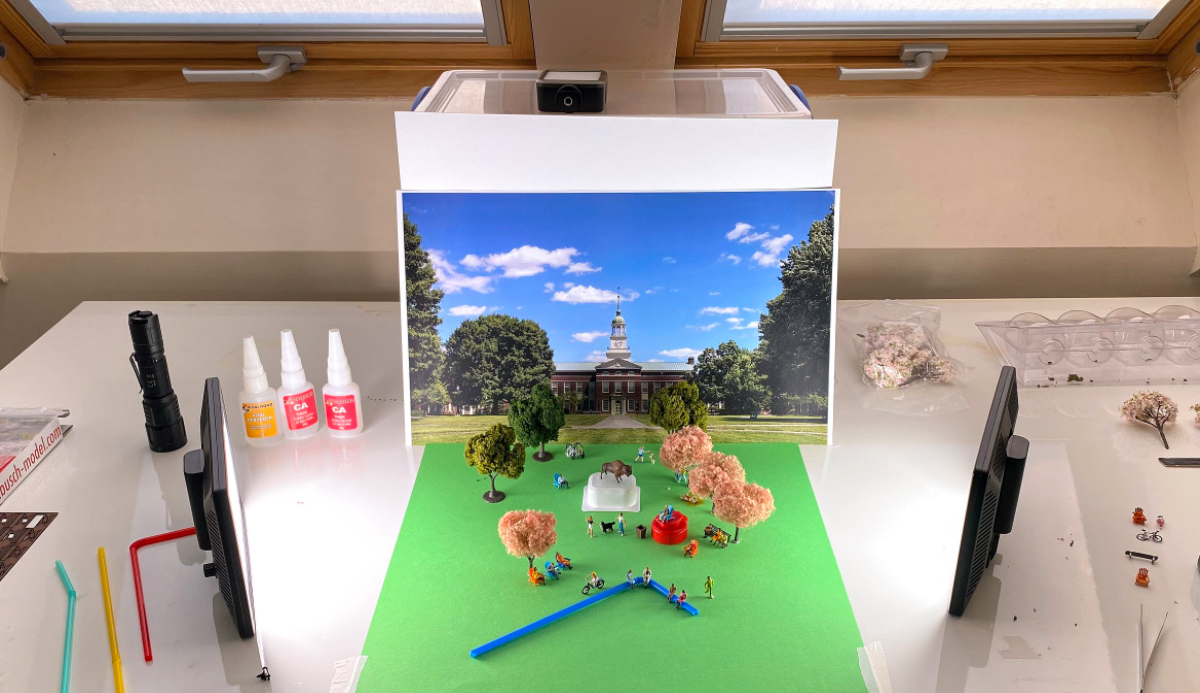

Data’s Creative Twist

photograph by Emily Paine

ata science isn’t just for engineers or analysts. It has the power to advance many different fields of study, sometimes in surprising ways. For example, it can help psychologists better understand children’s movement patterns or inspire creative writing. Showcasing the versatility of data science is a goal of Kelly McConville, director of the Dominguez Center for Data Science. Students who participate in the Data Science Student Fellows program are matched with project stakeholders and data-science mentors who guide fellows through technical and theoretical approaches to data-centric problems. Fellows are encouraged to apply their diverse perspectives to develop solutions. This spring, 29 students are working on 13 projects, gaining experience across a range of fields. Here’s a look at three.

Data Dance

The Collaboration: Led by mentors Professor Haley Kragness, psychology, and Claire Cahoon, digital pedagogy & scholarship specialist, fellows Claire Engel ’25 and Gwen Radecki ’25 are exploring how music and dance affect children’s physical and emotional development and how to measure those effects efficiently. Their project blends developmental psychology, music cognition and computer science.

Engel’s computer science & engineering major complements Radecki’s psychology and linguistics double-major, bringing a cross-disciplinary perspective to their work. They’re studying different ways to track movement in children’s dance by comparing methods like automatic tracking to manual labeling to determine the most effective approach for researchers.

“While I lack the technical expertise to implement automated movement extraction alone, this project provides me with the potential to address a major challenge in my work,” says Kragness. Using home videos of children dancing, they are comparing automated movement extraction to manual annotations to assess its viability in children’s dance research.”

Data Bloom

The Collaboration: Professors Sara Stoudt, mathematics & statistics, and Elinam Agbo, English — creative writing, are partnering with fellows Shaheryar Asghar ’28 and Caitlyn Hickey ’26 to explore how data and storytelling can intersect and inspire ecowriting for the journal The Dodge.

Asghar, a double-major in mathematical economics and psychology with a minor in English — creative writing, and Hickey, who studies applied mathematics and business analytics, are combining their skills in data analysis, app design and creative writing to develop an interactive app.

The project involves selecting nature-related datasets, developing writing prompts, and showing how data-driven insights can enhance creative expression. “Statistics requires creativity,” says Stoudt. “This project highlights that creativity while emphasizing the important role of writing in the statistical investigation process.”

Data Play

The Collaboration: Professor Jimmy Chen, analytics & operations management, is teaming up with Palmer “PJ” Steiner, assistant women’s soccer coach, and fellows Katherine Vice ’27 and Aiden Kim ’27 to develop a tool that will simulate Patriot League Women’s Soccer Tournament standings and clinching scenarios. By incorporating home/away status, past matchups and team performance metrics, they aim to support data-driven decisions during the season.

Kim, a computer science and data science co-major, and Vice, an economics major, are combining their skills to develop an interactive simulation dashboard. Kim is focused on predictive models and design, while Vice is analyzing results. “This project provides both a learning opportunity for students and practical benefits for the women’s soccer team, demonstrating the power of interdisciplinary collaboration,” says Chen.

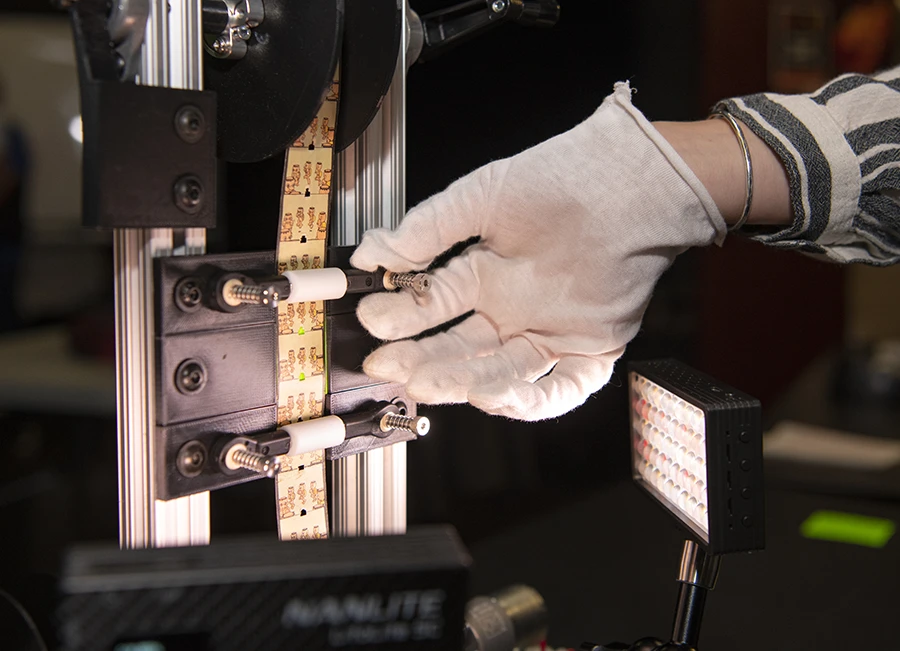

A Reel Discovery

photography by Emily Paine

nearly forgotten piece of cinematic history has been brought back to life, thanks to the research of Professor Eric Faden, film/media studies, and a team of Bucknell students. Their work has revived a rare set of Japanese short films from the 1930s while taking them across the globe in search of even more lost media.

Faden found the films by fluke in 2017 during a teaching fellowship in Kyoto. While researching another project at the Toy Film Museum, he discovered a set of reels made from paper, a medium rarely used in filmmaking. “The only other films made on paper were copies of early American ones for copyright deposit,” Faden says. “The Japanese paper films are very different in that they were meant to be projected from the get-go.”

However, due to the films’ fragility, museums were hesitant to project them.

Determined to preserve the films digitally, Faden began meticulously photographing each frame with the intention of stitching them together as a video. The task proved to be far from simple. Although each film only lasts between two and 12 minutes, it could take Faden up to four and a half hours to photograph one. Even then, the result didn’t achieve the desired effect of watching a continuous movie.

Recognizing the need for a new preservation method, Faden recruited the expertise of professors and students across disciplines. Alina Arko ’23, who studied mechanical engineering, designed a scanner delicate enough to handle the fragile paper reels while capturing them as a continuous video. Then, computer science students Yuhan Chen ’23 and Jackson Rubiano ’27 developed software to recognize frames and stabilize the images, ensuring the films could be projected in a fluid sequence.

The films represent a fascinating mix of genres, including wartime propaganda, instructional exercise reels, early anime and mythological stories featuring ninjas and samurai.

From the beginning, Faden’s goal was preservation, not restoration. “We wanted to show the films — warts and all — with their inconsistencies and the over-scanning so the audience could see how the film is working. A restoration project would remove all that.”

“It gave me perspective about the history and culture of Japan, which helped me understand the films I had been working on,” Rubiano says.

In August, the digitally preserved films were screened at a Brooklyn theatre. “I thought we would have six people, aside from my family,” Faden joked. Instead, the event was packed — 75 people were turned away once the venue hit capacity.

For his dedication to preserving these films, Faden was awarded the 2025 Sumie Jones Prize for Project Leadership in Japan-centered Humanities by the Association for Asian Studies.

Leaps and Bounds

For the triple jumper and cornerback, the journey from one sport to the other requires time management, no-days-off determination and a willingness to transform his physique from one season to the next.

As a football player, Sims needs muscle mass to jam or tackle, while as a track athlete, he requires lean muscle to run fast and soar far. Like 47 feet, 1 inch far, Sims’ best triple jump distance.

“After track season ends, I start to pack on my football weight,” he says. “I gain back about 10 to 15 pounds. It’s a totally different lifting program and training routine. Then, at the end of football season, that weight comes off, and I start my track training.”

This physical transformation is why some colleges avoid recruiting dual-sport athletes. Sure enough, in Sims’ junior year of high school, recruiters from other schools asked him to pick a lane. “They felt if I did two sports, it would take away from one,” he says. “In a way, I agree with that. I mean, I sometimes wish I did spring training for football or fall training for track. But it all comes together in the end, which makes it a really good experience for me.”

This do-it-all attitude formed at age 5 when Sims sought a way to connect with his athletically inclined older brother, Micah ’20. By middle school, Chris excelled in football, basketball and track at The Haverford School in the Philadelphia suburbs. Bucknell’s track team first offered him a spot, and the football team allowed him to walk on.

“It was a dream come true to start at a Division I level and play two sports,” says the economics major. “I just want to help the teams in whatever way possible.”

His team-first mentality explains why Sims was selected by his peers to be track team captain. He is willing not just to motivate his fellow jumpers but also to lift up the whole team.

Sims knows individual performances can boost the entire team’s morale, similar to how a key interception can change a football game. “If a distance kid runs really well, that’s awesome for our team,” he says. “It’s not just, ‘Oh, he set a PR [personal record]’ — it takes the whole team higher.”

Instant Replay

TEAMWORK

Nathan: Exactly. We don’t micromanage each other, and that lets us be in multiple places at once. We can divide our time between meetings in Washington, D.C., state capitals and international operations without losing momentum.

Nathan: Another advantage is continuity. One of us is always available, whether for travel, negotiations or strategic decision-making. In a single CEO structure, all that responsibility falls on one person, which can slow things down.

Nathan: We also communicate constantly. Our thought processes are so similar that if one of us makes a decision, the other would have likely made the same choice. This consistency provides clear direction for our team.

Nathan: Your team’s strength directly impacts the company’s success. We’ve made mistakes in both directions — hiring too quickly and not acting fast enough when someone wasn’t the right fit. Surround yourself with people who complement your strengths, and the business will thrive.

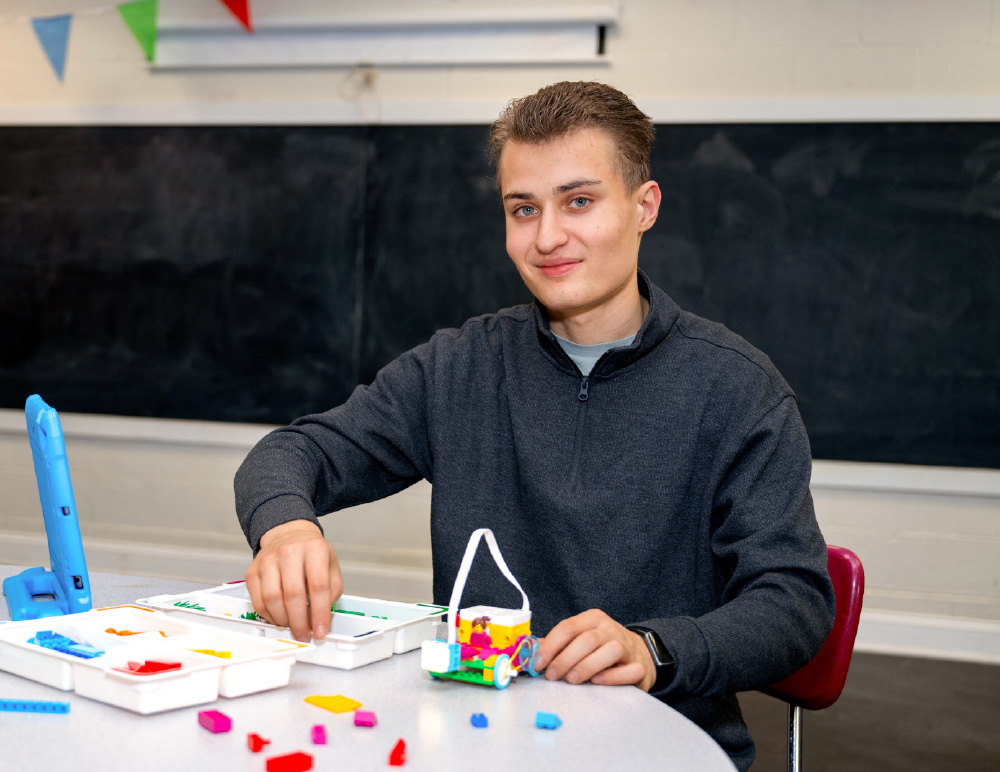

From Passion to Prototype to Profit

photography by Emily Paine

hen people think of entrepreneurship, they might picture tech startups, venture capital pitches and Silicon Valley innovators. But entrepreneurship often starts closer to home, with grassroots efforts, creative passion projects and small businesses that weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life.

Bucknell is embracing this vision with the Campus Shop — a new retail space launched by the Perricelli-Gegnas Center for Entrepreneurship & Innovation (PGCEI) and housed at the historic Campus Theatre in downtown Lewisburg. The shop gives Bucknellians an opportunity to sell their products and market their services directly to consumers, providing students with a hands-on understanding of entrepreneurship.

Waina Ali ‘26, a fellow with the PGCEI, has firsthand experience with the power of entrepreneurship. When her family relocated to Bloomsburg, Pa., in 2021, her parents took a leap of faith and opened a small grocery store.

“It taught me that entrepreneurship isn’t just about knowing everything from the start; it’s about figuring things out as you go,” she says. “My parents didn’t even have high school diplomas, but they built something meaningful by taking a chance.” Her family poured its energy and determination into the venture, creating not just a business but a hub of connection within the community.

Now, Ali is channeling her insights into helping others. She’s passionate about making the Campus Shop a space that welcomes all students, especially those who might not see themselves as traditional entrepreneurs.

“The shop shifts the focus and shows students that entrepreneurship is for everyone,” Ali says. “If you braid hair or knit scarves or make art, you can sell your pieces here. If you’ve come up with an innovative new product and want to test your prototypes with real consumers, you can do that here too.”

Erin Jablonski, director for the PGCEI, plays a key role in empowering students as they pursue their ventures. She provides coaching in areas like production and cost analysis, supporting students as they navigate the complexities of bringing their products to market. Once products hit shelves, Jablonski will review sales data and trends with the students to help them make strategic decisions to refine and grow their ventures. Students profit directly based on their pricing strategy, with 10% of sales going to the Campus Shop to fund its general operations.

Beyond students, the Campus Shop hosts entrepreneurs-in-residence, showcasing the work of Bucknell-affiliated artisans alongside the student vendors. Intertwining commerce and philanthropy offers students invaluable experience in managing, marketing and profiting from their creative endeavors while supporting the broader Bucknell community.

“This space isn’t just about products — it’s about empowerment,” Ali says. “As I talk to other students, I keep hearing, ‘I have an idea, but I don’t know what to do with it.’ The Campus Shop is here to help with that. You don’t have to know everything to start something.”

Creativity on Display

Jaycee Birkemeier ’27, biology, is using the Campus Shop to get her art in front of buyers.

Freeman College of Management student Sofia DelGrosso ’27 sells her collection of astrological cat stickers, Zodicatz (above, right).

Alexa Helmke ’27, undeclared, crochets accessories, including hats, mittens and handbags under her brand, the Crochet Wizard (above, left).

Dani Kuck ’27, undeclared, creates artistic stuffed animals.

Becca Lipsky ’25, music education, markets vocal lessons for solo and choral singers.

Peace by Piece, a nonprofit organization led by Bucknell students, sells individual students’ creations to support humanitarian causes.

Features

The Plastic Paradox

n November 2024, more than 3,000 delegates from around the world converged on Busan, South Korea. The meeting was meant to mark the conclusion of a two-year global process that had a single, ambitious goal — to resolve one of the most urgent environmental crises of our time: plastic pollution.

“For years, the UN had been working on adopting resolutions and encouraging governments, the private sector and environmental groups to address the issue of plastic waste leaking into the oceans,” says Stewart Harris ’95, who majored in biology at Bucknell and is now managing director of global affairs for the American Chemistry Council. “That issue evolved into the creation of this Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop a treaty.”

Established by the United Nations Environment Programme — the world’s highest decision-making body on the environment — the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) on Plastic Pollution had been tasked with forging a legally binding, international treaty to curb plastic waste. “Back in 2022, when they adopted the resolution, it was a very emotional time. There was a lot of enthusiasm and excitement about the road ahead,” says Harris, whose role as an observer and leader of the global chemical and plastic industry delegation requires him to provide professional expertise to the negotiators.

That road ran from Punta del Este, Uruguay, where the committee held its first session, through France, Kenya and Canada before arriving at its terminus in the Busan Exhibition and Convention Center, where roughly 3,300 delegates — including representatives from 170 nations and observers from more than 400 organizations — gathered to hash out the details.

However, what became clear over the course of the fifth session was that it would not, in fact, be the last. “When we got to Busan, I think there was a recognition that governments just hadn’t given themselves enough time to work through the complexity of these issues,” says Harris.

In less than a century, plastic has become quite literally embedded in every facet of life on earth. It inhabits both lung and brain tissue, can be found on Mount Everest and in the Mariana Trench, and is used to create everything from lifesaving medical and surgical devices to clothing, kitchenware and electronic components. The complexities of figuring out how to regulate such a material are many, to say the least.

What the INC negotiations prove is there is an overwhelming consensus that plastic pollution is a global problem. The lack of a treaty, however, demonstrates that there is decidedly less unity around a global solution, though this does not mean there isn’t one. As deliberations continue into 2025, Bucknellians of all stripes — scientists and researchers, economists and industry leaders — are working toward a future in which plastics are as sustainable as they are necessary.

The Plastics Life Cycle

One widely accepted method for understanding the environmental impacts of this cycle is to perform what’s called a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment (LCA).

“You’re looking at the life cycle from its infancy when raw materials are extracted from the earth, all the way to where a product ends up in the end-of-life scenario,” says Rochelle Fisher Bradford ’94, a Bucknell chemistry graduate who led the sustainable materials team for global packaging at Coca-Cola. (Coca-Cola was somewhat of a trail-blazer in this space and is often credited with having performed the first LCA in the country in 1969 when it examined emissions outputs and waste flows of beverage containers.)

For most consumers, the lifespan of a plastic product begins and ends with its usability. This is particularly true of single-use plastics. A high-density polyethylene grocery bag exists for the half hour it takes to get food from the checkout counter to the kitchen pantry. A polyethylene terephthalate (PET) water bottle lives and dies between the first sip and the last. A polypropylene wet wipe survives the few seconds it takes to wipe down your hands. Then, poof: into the garbage or the recycling bin.

However, there is a vast distance between the lifespan of the product and that of the polymer. Polyethylene and polyurethane can take hundreds of years to decompose, if not longer. Current estimates suggest the world produces between 350 and 450 million tons of new plastic waste each year, approximately half of which is composed of single-use plastics, so there is a significant push to focus pollution mitigation efforts on the tail end of the life cycle.

“What the industry is trying to do as a whole is find a better alternative than throwing it all in a landfill,” says Bradford, who in her role at Coca-Cola helped shepherd an initiative to make all consumer-facing plastic recyclable in the coming years. “Using a method called mechanical recycling, you can basically take a PET bottle that’s been used, chop it up into a bunch of pieces, clean and sterilize it and melt it down and form another bottle.”

An emphasis on recyclable materials is a step toward the cradle-to-cradle approach, in which products and materials can exist in a closed loop of infinite circulation rather than becoming waste.

In theory, every type of plastic is recyclable insofar as it has the ability to be recycled. In practice, however, challenges remain.

A Plastics Lexicon

chemical recycling: an advanced form of recycling that seeks to convert plastic waste back into raw materials for the manufacture of new plastics

mechanical recycling: the processing of plastic waste without altering the chemical structure of the waste; includes the collection, sorting, washing, drying and shredding of waste materials

microplastics: plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size, the majority of which are produced by synthetic textiles, car tires and city dust

nurdles: very small beads or pellets of plastic that serve as raw material in the manufacture of plastic products (pictured above)

Plasticene: a proposed new age in Earth’s history, contained within the Anthropocene epoch, which begins with the proliferation of plastics in the 1950s and the incorporation of plastics into the geologic record

single-use plastics: goods made from fossil fuel-based chemicals that are meant to be disposed of after use:

bottles, cutlery, cups

shampoo bottles, milk bottles

bags, food packaging, freezer bags

drinking straws, microwave dishes, bottle caps, wet wipes

cutlery, plates, cups

protective packaging, hot drink cups

The Afterlife of Plastics

“They did something really clever to save face and keep the heat off their industry, which was to create the recycling code numbers with the three arrows that you find on plastic products,” says Thomas Kinnaman, Bucknell’s Charles P. Vaughan Chair in Economics, who researches global trends in recycling. “They were worried that plastic would be banned, so rather than change their product, they shifted to telling the public that everything was recyclable.”

Post-consumer plastics are typically labeled with numbers, starting with one designating PET, the most commonly recycled plastic, all the way up to number seven, a catchall that includes everything from nylon to polycarbonate.

While PET and high-density polypropylene are more easily and therefore more commonly recycled, certain specialized plastics, such as those coded seven, can contain mixed materials or toxic substances that are difficult to process. However, challenges aren’t purely technical, as recycling infrastructure — or the lack thereof — significantly affects recyclability.

“It doesn’t matter if you create a magic material if you can’t scale it,” says Bradford. “The whole idea of recycling is dependent on a lot of different parts of the value chain working together. Not only does the material have to be recyclable, but somebody has to collect it. Somebody has to sort it. Somebody has to clean it. Somebody has to break it down to its original polymers and put it back together. And there has to be a market for it.”

Microplastics, classified as particles less than 5 millimeters in size, are transported not only through water, but air, dust, rain and snow, by which they’re deposited in remote locations all across the world, from Antarctic sea ice to deep ocean trenches.

The ubiquity of microplastics raises serious questions about pollution mitigation efforts that focus on the end of the plastic life cycle, if only for the simple fact that the life of plastic doesn’t really have an end. So a cradle-to-grave analysis is somewhat of a misnomer, as plastic neither dies nor rests; it just breaks down into infinitely smaller and smaller particles, eventually achieving a kind of omnipresence. The paradoxical truth about plastics is that it is impossible to imagine a world without them — for better and for worse.

Perhaps the answer lies in reimagining what plastics are altogether — from the first stage to the last.

a lesson from ‘the Graduate’

The dark actualities beneath the sparkling appearances of plastics were clear to Braddock, figuratively in the duplicitous characters around him and literally in the duplicitous career before him. The actualities were also clear to us, or plastics as a metaphor for the characters would have failed in the film. But it worked because it expressed the essence of plastics in America: like the characters, glitzy at first glance but destructive at heart.

Plastics were patriotic when they entered American life after World War II, having provided parts for airplanes, weapons and other military needs. They enabled a consumer culture previously unknown to us, fueling our American idolatry of efficiency, affordability, effectiveness and ease. “Plastics: A Way to a Better More Carefree Life,” declared House Beautiful magazine in 1947.

All that glitters is not gold. By the first Earth Day in 1970, the same year President Richard Nixon created the EPA, the ecological costs of plastics were stark. Smog from factories making everything from Frisbees to Barbies smeared the sky, trash incinerators burning plastics further toxified the air and mountains of plastics rose in landfills, recycling and regulation nascent. Ever since, as plastics have become more prevalent and harmful — last April, the same EPA called plastics pollution “ubiquitous”— we’ve discovered plastics everywhere in our world and in ourselves, exacerbating societal ills from cancer to climate change.

“Yes, I will,” Braddock responds.

“Ssh, enough said,” McGuire whispers. “That’s a deal.”

Sustainable Solutions

Before plastic is recycled or deposited in a landfill, before it is used or consumed, before it is transported to store shelves or processed and manufactured, it is extracted from the earth in the form of oil, gas or coal.

Or at least, this is true of 99% of plastics. Contained within the other 1% is a range of novel technologies and materials that reconceptualize the entire life cycle of plastic.

“People tend to use the terms ‘bio-based plastics’ and ‘biodegradable plastics’ interchangeably, but they’re actually different,” says Professor Kat Wakabayashi, chemical engineering, who for the last 15 years has been working with polylactic acid (PLA), a bio-based and biodegradable plastic material derived from fermented plant starches. “Our lab works on modifying these bioplastics so that we end up with a more consistent, more well-behaved product.”

To do that, he and his students purchase commercial PLA pellets, roughly the size and shape of Nerds candy, and reinforce them with bio-based cellulose fibers derived from wood pulp from a sustainably managed forest in Maine. Using his lab’s solid-state shear pulverization extruder, he compounds small pieces of these cellulose fibers with PLA to create a stronger, more reliable material that resists softening at low temperatures.

Wakabayashi’s research is also concerned with the end-of-life scenario for PLA. Its low heat stability can make it challenging to mechanically recycle, but it can biodegrade within months under the right industrial composting conditions. In collaboration with the Bucknell Farm, Wakabayashi and his students developed a custom soil degradation apparatus to evaluate the biodegradability of their PLA samples. “We have actually seen signs and measurements of polylactic acid degrading in our controlled environment in the lab, so that’s a good sign,” he says.

While PLA is one of the most prevalent commercial bioplastics worldwide, among the most promising polymers of the future is polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) — a bio-derived and biodegradable plastic.

“PHB is made as an emergency food source in bacteria,” says Professor Hannah Yocum M’16, chemical engineering. Yocum’s research in metabolic engineering started with making precursors to antibiotics, though she eventually discovered that the application of different enzymes to those precursors could be used to produce bioplastics like PHB. “We found you can take the genes that code for the enzymes that make the bioplastic and put them into another microbe and make more bioplastic,” she says.

PHB is easily and quickly biodegradable and biocompatible, meaning that it is well suited for biomedical applications, such as medical implants and sutures.

The end-of-life scenario of even bioplastics poses familiar challenges. One solution for reducing waste could lie in reengineering traditional plastics to better close the life-cycle loop.

Students working to reduce

society’s carbon footprint

Mikey Brandt ’26, markets, innovation & design

EcoMark: a biodegradable marker

Morgan Powell ’26, civil engineering

Trapped Grass: Replacing unused grass with native plants

Forevergreen: Tracking and offsetting carbon footprints

A Catalyst for Change

Though not all methods of recycling are created equally.

Mechanical recycling involves the melting and shredding of material without altering the chemical composition. “You can melt polyethylene down and reprocess it, but there’s a finite number of times you can do that,” says Mara Kuenen ’18, who majored in chemical engineering and is now a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry at the University of Minnesota. “With chemical recycling, you actually break down waste at a molecular level to return it to those original monomers.”

Kuenen’s research with polyethylene involves devising strategies to make traditional plastics more recyclable. “We’re trying to design materials from the bottom up so their recyclability is inherent in them from the beginning,” she says. “We want to make those strong chemical bonds breakable under specific circumstances, so something like your water bottle doesn’t degrade in your hand while you’re drinking from it, but it does easily degrade with the right trigger.”

In Kuenen’s research, that trigger involves using small alcohol molecules to break down her polyethylene-like polymers into individual molecules that can be repolymerized into new, high-quality plastics. The same premise informs the work of Philip Onffroy ’22, who studied chemical engineering at Bucknell and is now a doctoral candidate at Stanford University.

Plastics recycling that relies on specific biological catalysts is still in the early stages of research, but the technology could help build a circular economy and reduce plastic waste.

Even so, the existence of the proverbial “magical material” is still constrained by problems of scale and economic viability. “I can do things at my lab bench to make something that is recyclable, but if there’s not an economic incentive for it or a policy to support it, then it’s not going anywhere,” says Kuenen. “My polyethylene materials aren’t going to solve the plastic waste crisis. Sure, they may be a part of a solution, but for these global changes to happen, we really need policy changes.”

In the spirit of circularity, it all comes back to Busan and the need for a global treaty.

“While they didn’t finish the negotiations, they did make a ton of progress on some key areas,” says Harris. “Things like extended producer responsibility are in there. Things like calling on governments to establish targets for recycling rates and for access to recycling are in there.”

As someone who has witnessed the negotiation process from its inception, Harris foresees an eventual treaty as a necessary catalyst to inspire a broad array of solutions, from improved and expanded recycling infrastructure to greater investment in bio-based and biodegradable plastics. “It’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all, universal solution,” he says. “Once governments complete negotiations and they move to implementation, the private sector in general is going to have a huge role to play in implementing the solutions. The treaty sends a signal to the private sector to accelerate investments and innovation.”

Taylan Stulting ’16, who discovered rowing at Bucknell, is gearing up to cross the vast Pacific Ocean.

Waves of Change

Rowing 2,800 miles across the Pacific is a grueling test of endurance, strength and courage. But for Taylan Stulting ’16, a greater mission drives every stroke.

photography by Kelly Davidson

t first glance, horseback riding and ocean rowing might seem like entirely unrelated pursuits. But for Taylan Stulting ’16, growing up in the saddle in South Carolina turned out to be more than just a childhood pastime — it would serve as a foundation for something much more extreme.

When faced with eight-foot waves during an overnight training row off the coast of Massachusetts, Stulting instinctually engaged their core and hips, rolling up and over the surging waters with remarkable balance and poise.

“It’s like riding a mechanical bull,” says Stulting, who is non-binary. “It’s not uncommon to fall off your seat. That’s why you’re always tethered.”

Waves of Change

by Caleb Daniloff

photography by Kelly Davidson

Taylan Stulting ’16, who discovered rowing at Bucknell, is gearing up to cross the vast Pacific Ocean.

t first glance, horseback riding and ocean rowing might seem like entirely unrelated pursuits. But for Taylan Stulting ’16, growing up in the saddle in South Carolina turned out to be more than just a childhood pastime — it would serve as a foundation for something much more extreme.

When faced with eight-foot waves during an overnight training row off the coast of Massachusetts, Stulting instinctually engaged their core and hips, rolling up and over the surging waters with remarkable balance and poise.

“It’s like riding a mechanical bull,” says Stulting, who is non-binary. “It’s not uncommon to fall off your seat. That’s why you’re always tethered.”

The racing event, organized by World’s Toughest Row, pits rowers against each other and the vast and unpredictable Pacific Ocean with the promise of “sleep deprivation, hallucinations, blisters, sores, tears and pain” alongside “camaraderie, self-discovery and unparalleled pride.”

As one of eight boats preparing to set a course for Hawaii this spring, Stulting’s team aims to complete the crossing — a distance greater than the width of the Atlantic Ocean — in around 40 days (with an eye on the world record of 38 days and 12 hours), navigating a wild waterscape with waves as high as 20 feet while avoiding cruise ships and container vessels.

But the challenge is not just about physical endurance or chasing a record. It’s about transcending mental and emotional barriers — pushing through exhaustion, confronting fears and overcoming the isolation that comes with spending weeks on the water with minimal rest.

It’s also about representation. If successful, Stulting, a doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, will be the first out transgender rower to complete the feat.

“Growing up in South Carolina, there wasn’t much visibility for trans people, especially in sports,” Stulting says. “This journey is about proving that we belong.”

Callouses and Camaraderie

Fresh off a 21-hour training row this past October, Stulting and teammates Courtney Farber and Julie Warren relaxed on the patio of Mission Boathouse, a waterfront restaurant overlooking Beverly Harbor, about 20 miles north of Boston. Under clear, breezy skies, they compared calloused hands and dug into plates of pasta and snacks, their faces chapped by wind and saltwater spray.

As the breeze picked up and the pasta quickly disappeared, their conversation shifted to the technical aspects of the sport, including how to deploy the para-anchor, a parachute-like device that sits just below the water’s surface, keeping the boat in place when heavy weather prevents rowing. They practiced putting on the immersion suit, a crucial piece of gear that allows a team member to stay dry while performing tasks like cleaning barnacles off the hull or repairing a damaged rudder (sometimes a casualty of marine life collisions). They also reviewed person-overboard drills, tested different row-shift patterns and honed the logistics of eating, sleeping and using the bathroom in cramped quarters.

“Basically, we’re figuring out how to exist on a 29-foot boat in tight spaces,” Stulting says.

“When I first learned about ocean rowing, I thought it was just for wealthy people who could take six months off and buy a boat,” Stulting says. “But this four-woman team seemed like average folks.”

A seasoned world traveler with a taste for offbeat pursuits like roller derby, flying trapeze and skydiving, Stulting was inspired to pursue the same dream. They put out a call for potential teammates on Facebook and interviewed more than 25 candidates across several months. “You have to make sure you’ve got the right people for something like this,” Stulting says. “How do you handle conflict? What are you like at your worst? What is your ‘why’? This journey is as much about the people you’re rowing with as it is about the ocean itself.”

Taylan Stulting ’16 and their crew will row — and eat and sleep — aboard Emma for about 40 days.

Taylan Stulting ’16 and their crew will row — and eat and sleep — aboard Emma for about 40 days.

“On a personal level, I want to know what I’m made of,” Farber says. “This will be a serious test. And as an ally, it’s about walking the walk and normalizing that there’s space for us all.”

Warren, a collegiate rower from Smith College, works as a rowing coach and nanny in Chicopee, Mass. She was drawn to both the challenge and the inclusive nature of the venture.

“It’s important to do hard things in life,” Warren says. “I don’t know yet what the ocean will teach me, but I know it will teach me something worth finding out. And supporting a charity that helps LGBTQIA+ athletes — it’s amazing to be able to support an organization working to make sure we all can continue to have a place in sport.”

Stulting named the team “Oar the Rainbow” and founded a nonprofit to raise funds for Doctors Without Borders and Athlete Ally, an organization working to combat homophobia and transphobia in sports.

For Stulting, the journey goes beyond advocacy. “I’m a survivor of child sexual abuse, and sports have always been a way for me to reclaim my body and rewrite my narrative,” they say. “Doing something on this scale is the ultimate reclamation.”

Finding One’s Place

“I realized that I had the potential to tackle anything with the right support,” says Stulting, who decided to pursue a major in women’s & gender studies. “It was empowering to know that I could make decisions based on what I wanted to do, not just what others expected of me.”

This support extended to their activism in LGBTQIA+ causes across the state. “I missed class more than I should have,” they say. “But my professors worked with me to figure out how to make up assignments because they knew what I was doing outside of school was important to me.”

Braving the Pacific

Designed for safety, Emma is a self-righting vessel. Rowers are tethered by harnesses and lifelines, and the boat carries a life raft, satellite phones and an emergency go-bag. Even the oars are clipped in, with a spare pair on hand. One of the watertight hatches stores the lithium-ion batteries that supply power to the boat’s technology and lights. It also runs the watermaker, which desalinates seawater, producing up to 18 liters of potable water daily for drinking, washing and hydrating dehydrated meals.

The boat features small cabins at the stern and bow: One houses the autopilot and navigation system; the other stores medical supplies and repair tools. Both berths serve as sleeping quarters, with just enough headroom to kneel. “We call them our New York City apartments,” Farber quips. Despite the high-tech gear, Emma offers no luxuries — rowers rely on buckets for waste and hygiene, with “foolproof” methods to tell them apart in the dark, Stulting says with a wry grin.

Like any extreme sport, ocean rowing requires rigorous preparation — mental, physical and technical. The crew undergoes extensive safety courses, navigation drills and radio training. Their coach, Duncan Roy, a seasoned English ocean rower and world record-holder, stresses the importance of mindset.

“Quite often, the biggest challenge is the unknown,” Roy says. “Over the past two years, Taylan has shown relentless drive, determination and focus. These qualities will be invaluable on the Pacific Ocean.”

While the team is still working out the shift cadence, the launch will likely require all hands on deck. Launching off Monterey’s coast is expected to be tricky due to the tides, waves and varying depths. Emma will weigh close to 2,800 pounds fully loaded. “Wind can push a rowboat more quickly than a rower can row,” Stulting says. “A big concern is being blown ashore or into rocks.”

Once the boat is past the continental shelf, the path will be wide open. Stulting anticipates the first few weeks will be cool and rainy, followed by sunnier conditions. Sun shirts, wide-brimmed hats and sunscreen will be essential for the journey.

And when those final strokes are taken in Hanalei Bay, the crewmates fire off celebratory flares per tradition and awaiting friends and family come into view, Stulting imagines stepping onto the beach with wobbly legs and a mix of triumph, pride and transformation. “We have to wade through the water to get to land, and I think a lot about how it will be this almost poetic transition.”

Back at the dock in Beverly, boats are mooring as the sun begins sinking, gulls wheeling overhead. From Emma’s stern, an American flag and a pride flag flap in the breeze, a testament to the team’s mission and identity. Nearby, a pleasure boat flies American and Trump 2024 flags. Despite the political climate surrounding the transgender community, Stulting reports no hostility from other boaters.

“For this journey, being trans simultaneously has mattered a lot and meant nothing,” they reflect. “Once we’re on the boat, we’re just there to eat, sleep and row. That’s all we do.”

The Boat: Emma

This will be her fifth ocean crossing.

Night Rowing

The cabins use red interior lighting so the crew’s eyes can more easily adjust to the dark.

A tricolor navigation light is on top of the bow cabin on about a foot-and-a-half-long pole so it can be seen above waves at night: A white light is facing stern, a red light on port and a green light on starboard.

Watermaker

Pacific Ocean

Nutrition

In Stulting’s bag: Pop-Tarts (cookies and cream), Pringles and Trader Joe’s chocolate wafer cookies with peanut butter dipping sauce.

Land Training

Playlist

Night Rowing

The cabins use red interior lighting so the crew’s eyes can more easily adjust to the dark.

A tricolor navigation light is on top of the bow cabin on about a foot-and-a-half-long pole so it can be seen above waves at night: A white light is facing stern, a red light on port and a green light on starboard.

Watermaker

Pacific Ocean

Nutrition

In Stulting’s bag: Pop-Tarts (cookies and cream), Pringles and Trader Joe’s chocolate wafer cookies with peanut butter dipping sauce.

Land Training

Playlist

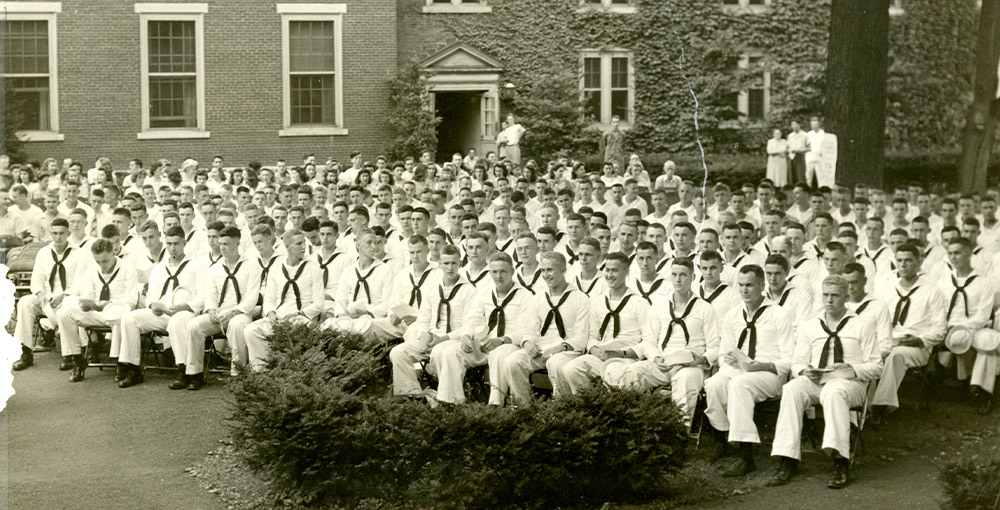

175 Commencements

From its modest start with just seven graduates to today’s grand celebration of nearly 900, Commencement is the University’s most anticipated event of the year. As we mark the 175th edition of this tradition, we look back at the milestones that shaped this event — each a testament to Bucknell’s growth and enduring legacy.

photographs: courtesy of Special

An undated photo captures Commencement between 1926 and 1932 (top); the legacy continues in 2024 (bottom).

An undated photo captures Commencement between 1926 and 1932 (top); the legacy continues in 2024 (bottom).

From its modest start with just seven graduates to today’s grand celebration of nearly 900, Commencement is the University’s most anticipated event of the year. As we mark the 175th edition of this tradition, we look back at the milestones that shaped this event — each a testament to Bucknell’s growth and enduring legacy.

by Susan Falciani Maldonado, Eir Danielson and Katie Neitz

photographs: courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives; by James T. Giffen

Origin Story

Dressing the Part

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

Photo: Emily Paine

Changing Venues

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

Honoring Luminaries

Honoring Luminaries

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

When Duty Called

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

Photo: April Bartholomew

Steps Toward Equality

Women had studied at the University since its founding, but primarily in secondary education programs in the Female Institute, a seminary affiliated with the University. In 1885, Chella Scott became Bucknell’s first female graduate. Scott’s achievement occurred when higher education for women was still a relatively new concept.

In 1875, Edward McKnight Brawley became the first Black student to earn a bachelor’s degree from Bucknell. Brawley went on to become a minister, religious scholar and journalist who served as the president of Selma University and Morris College.

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections/University Archives

Jessica Livingston ’93 To Address 2025 Graduates

Jessica Livingston ’93, co-founder of Silicon Valley’s renowned startup incubator Y Combinator, will deliver the 175th Commencement address May 18. A leader in entrepreneurship and innovation, Livingston has helped launch over 5,500 startups, including Airbnb, Reddit and Stripe. Livingston, who majored in English, exemplifies how a Bucknell education can lay the foundation for a transformative, world-changing career.

‘ray Bucknell

In the Face of Uncertainty, Follow the Mission

The new year ushered in a pervasive sense of uncertainty for higher education that is perhaps unmatched in modern times, and it impacts all of us, regardless of our political beliefs and regardless of ultimate outcomes.

We are closely monitoring all developments and working to identify the best courses of action we may need to take to follow the law while also upholding our institutional mission and values. This is challenging, as the legal implications of the multitude of actions and statements coming from Washington are not always clear, and they sometimes contradict Pennsylvania law.

What is clear to me, as the proud president of Bucknell for nearly 15 years and as a professor and administrator at Stanford for even longer than that, is that higher education in the United States now faces a potentially seismic shift. After spending the last 50 years “in college,” as I like to say — and living on a campus for 46 of them — I know more than a bit about the complex inner workings of these special and in many ways quite decidedly American institutions. I also am deeply aware of the broad spectrum of beliefs regarding what higher education is and what it should be. And I must urge everyone to not fall for the easy platitudes I hear repeated by all sides.

Whether public or private, large or small, colleges and universities are bracing for the potential loss of federal funding for research, which will impact medical and scientific advances for decades to come. They’re preparing for the possibility of increased visa scrutiny for current and future students and professors, which could reduce enrollment and faculty expertise. They’re studying the impact of potential cuts to federal student aid, which could put paying for college out of reach for students of modest means.

At the same time, the abrupt elimination of federal jobs has affected tens of thousands of workers, which directly impacts those with children in college and could increase their need for financial aid.

These issues are complex and in many ways challenge the basic foundational principles of our work as educators. We are constantly evaluating our legal obligations as circumstances continue to evolve. While we will meet the institution’s legal obligations, we will uphold our core values of academic freedom and student-centered residential education in a welcoming community where everyone can thrive.

Above all, we remain deeply committed to our mission and to serving and educating all Bucknell students, all of whom deserve to be here. We must continue to facilitate their learning and growth so they can develop intellectually and personally and discover their purpose in life. We must ensure Bucknell is an inclusive community that welcomes free expression and the exchange of ideas — a place where all can thrive and reach their fullest potential. These values drive every decision we make and unite us in purpose, as they have since our founding.

Higher education is facing complex challenges, but it is worth noting that a crisis can be the catalyst for unexpected breakthroughs. This moment in Bucknell’s history presents the opportunity to recommit to our mission in new ways. As we navigate a changing landscape, we will consider all options to best meet the evolving needs of our community. With thought and care, we will focus on being more innovative than ever before and emerge even stronger. Our commitment to you, and to all Bucknellians to follow, remains steadfast.

President

The Rhythm of Change

In Brassroots Democracy: Maroon Ecologies and the Jazz Commons, which was named a Best Book of 2024 by PopMatters, Barson explores how Black musicians shaped music into a world-making force that impacted everything from the Haitian Revolution to Reconstruction and the birth of jazz. Building on Julius S. Scott’s The Common Wind, a book that details the networks of information about the Haitian Revolution that spread across the Caribbean, Barson’s research demonstrates that music was a powerful force in responding to systems of slavery and imperialism. “I wanted to call attention to this acoustic, kinetic moment that inaugurated this new age of revolution and trace how song, rhythm and instrumentation articulated itself in these pivotal moments,” says Barson.

Both a jazz musician and a community activist, Barson has long been interested in the relationship between music and social movements. While he was an undergraduate at Hampshire College, his African American studies courses revealed a connection between the ethos of music and the history of the campaign for equal rights. Barson continued to investigate these topics while pursuing his doctorate in music at the University of Pittsburgh. “It was acknowledged that the 1960s were a time of convergence between questions of social relations, the political imaginary and developments in music,” he says. But Barson also questioned whether there was a deeper, more dynamic history to be unearthed. “This book emerged from my Ph.D. research, and my Ph.D. research emerged from feeling the power of music across historical contexts.”

Of particular importance to grassroots democracy movements was the formation of large brass bands, which were composed of both freedpeople and formerly enslaved people. These bands frequently performed at mass meetings, rallies and parades, often improvising musical arrangements as a mode of political expression. “Being innovative and being able to improvise were markers of being politically aware,” says Barson.

Spontaneous improvisation is commonly associated with jazz music, which Barson links to the mass movements of freedpeople that mobilized in confrontation with the institution of slavery. “Improvisation has always had a dynamic social commentary that reflected the spirit of the times,” he says.

Given the improvisational nature of jazz, there is a commonly accepted refrain that you’ll never hear the same jazz performance twice. In this way, jazz does not repeat itself, though it contains the rhythms of history.

Faculty & Alumni Books

The Lives of Bats: A Natural History

(Princeton University Press, 2025)

Professor DeeAnn Reeder P’16, a renowned expert in bat biology, offers a comprehensive exploration of bats, which play an essential role in ecosystems worldwide. The Lives of Bats offers a visually stunning look at these often misunderstood creatures. With over 1,400 species of bats inhabiting nearly every part of the globe, they contribute to controlling insect populations and pollinating plants, yet they remain largely underappreciated.

Editor’s note: The magazine will explore Reeder’s work — including her role as a research associate for the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution — in an upcoming issue.

Richard Zanetti ’61, M’64

Vector: A Thriller

(Archway Publishing, 2024)

Zanetti, a retired publishing executive, chemical engineer and Army veteran, brings his diverse experiences to Vector. His background, including work in environmental safety, informs this suspenseful story.

Share Your Work With Us

A Stellar Career

Tramm didn’t always dream of exploring space. But an internship as a systems operations engineer with Northrop Grumman and an astrophysics class taught by Professor Michele Thornley, physics & astronomy, got the mechanical engineering major thinking about how she could apply her skills to the great beyond. “I was able to dip my toe into the subject at Bucknell, which helped me realize it was something I wanted to explore more,” she says.

With the help of her professors, she was accepted into a graduate astrophysics program at Rochester Institute of Technology. There, she discovered a love of instrument engineering for astrophysics, which involved launching sounding rockets carrying scientific instruments into space. Her research helped her formulate a clear picture of her ideal career. “I didn’t think it was possible to work for NASA — it’s everyone’s pipe dream,” she says. “But when I got the job offer, I knew it was what I wanted to do.”

At JPL, Tramm has worked on instrument operations for the Mars Perseverance rover and Earth-observing satellites like Sentinel-6, which measure sea-surface heights to understand climate change. “Everyone I work with is doing something that’s never been done before,” she says. “We’re always doing things for the first time.”

Life Lessons

For high school teacher John Quinn ’18, a quality education goes beyond the classroom

As a posse scholar at Bucknell, John Quinn ’18 learned the importance of giving back to his community. After graduating with a degree in history, Quinn returned to his home district of Prince George’s County Public Schools, where he teaches AP and IB psychology and government at Frederick Douglass High School. He has also advised the National Honor Society, coached the debate team and helped found the school’s mental health club.

Quinn’s time at Bucknell taught him that the value of education extends beyond the classroom. “The experience at Bucknell was just as much about what happened outside of the classroom as inside of the classroom,” he says.

In his first year of teaching, Quinn was named High School Male Educator of the Year by his district. He went on to earn his master’s from Teachers College at Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on implementing a positive psychology curriculum to explore adolescent identity development.

“A Bucknell education instills in you how important it is to learn about the injustices in society, the inequities, especially in public education,” he says. For Quinn, tackling those injustices often takes place at the individual level. “Mentorship between students and young teachers is key,” he says. “Being able to connect with young people is both important and rewarding.”

Looking ahead, Quinn aims to drive systemic change as an administrator. He joined his district’s aspiring leaders program and hopes to become an assistant principal and, eventually, a principal.

Restoring Justice

While studying at University of Southern California Gould School of Law, Coleman joined the Post-Conviction Justice Project (PCJP), where he provided pro bono representation to incarcerated individuals before the California Board of Parole. “These people have been rehabilitated and paid their debt to society, so we should help them reintegrate,” he says.

His work with the PCJP led him to pilot a restorative justice program in Long Beach, Calif., where community members help determine responses to crime. “It’s taught me that, sometimes, people just need a second chance,” says Coleman, who serves as the vice chair of the Ethics Commission for the City of Long Beach.

In addition to his commitment to restorative justice, Coleman practices intellectual property and privacy law. “In private practice, I represent large corporations in relatively sophisticated matters,” he says. “Shifting from my practice to restorative justice work reminds me of why I went to law school in the first place. It’s an honor to advocate for others.”

Powering Progress

In 2023, he founded Brainforge, a company that helps organizations uncover insights, cut costs and grow revenue. For Kumaran, Brainforge represents the culmination of years spent solving complex problems and improving decision-making. As a leader, he prioritizes fostering a culture of continuous improvement and a fail-fast mentality. “Every day, we challenge ourselves to be better than we were yesterday,” he says.

Kumaran traces his entrepreneurial mindset to Bucknell, where mentors and resources from the Small Business Development Center (SBDC) helped shape his approach to problem-solving. “The collaborative environment at Bucknell gave me the tools to think critically and creatively about real-world problems,” he says.

The son of first-generation immigrants, Kumaran planned to attend college in his native California but followed his father’s vision for a liberal arts education on the East Coast. A chance meeting with a professor during an impromptu tour of the Dana Engineering building convinced him Bucknell was the right fit. “Getting a one-on-one tour was a game-changer,” Kumaran says. “It showed me that Bucknell was a community where people care.”

Kumaran majored in computer engineering but explored beyond his field. As a sophomore, he approached Professor Curtis Nicholls, the Kiken Family Chair in Management, about joining Bucknell’s Student Managed Investment Fund, which is typically reserved for senior management students. With the help of Nicholls, Kumaran took summer courses to acquire the prerequisites for the capstone course. He also got involved in the SBDC and co-launched Maker EDU, a venture that helped schools build makerspaces, which gave him his first taste of entrepreneurship.

After graduating, Kumaran worked in data roles at startups like WeWork and Flowcode, managing projects from sales analytics to scaling data teams. Seeking more independence, he launched Brainforge, leveraging his network — including Bucknell connections — to build the business. Today, Kumaran leads with a focus on empowering clients and exceeding their expectations. “Our goal is to be indispensable to them,” he says.

No Business Like Show Business

“Young music directors tend to take on a lot of far-flung contracts. I‘ve done theatre in Indiana and Massachusetts. I’ve toured with Beautiful: The Carole King Musical and Mamma Mia!,” says Golden, who has hit most of the continental U.S. while touring on productions. “But all of that adds up. Every job I’ve had has led to the next job, which has now led me to New York City.”

During The Notebook‘s 10-month run on Broadway in 2024, Golden worked as the production‘s associate music director and associate conductor. If there is a dictum that undergirds her work, it is that practice makes perfect.

“It begins with three weeks in the rehearsal room, where I teach music to the actors and act as a liaison with the rest of the creative team,” she says. Then comes tech rehearsal, where she helps integrate design elements — like a scene featuring live rain on stage — and works with the orchestra. When the production went live, Golden attended eight shows weekly. “Even after our 250th show, we were still refining things,” she says.

Golden’s role came full circle when she found herself working alongside composer, singer and songwriter Ingrid Michaelson, who composed The Notebook’s music. “At Bucknell, my a cappella group, Two Past Midnight, performed Ingrid Michaelson songs,” says Golden. “Years later, I was able to translate her new music into the show and teach it to the actors.”

Bucknell Choirs Reunite

The event, led by University Choir Director Caleb Hopkins and Rooke Chapel Choir Director Emeritus Bill Payn P’00, was the first of its kind in more than a decade. “For many alumni, singing in a choir was a seminal part of their Bucknell experience,” Hopkins says. “This was an opportunity to celebrate the shared legacy of choral excellence between them and the current students.”

The weekend included rehearsals, social events and a banquet. The highlight, Hopkins says, was a joint performance featuring works beloved by alumni and students, including Elaine Hagenberg’s “O Love,” Ola Gjeilo’s “The Ground” and Payn’s own “Walk Humbly.” The concert also premiered “Who Walk This Way,” a newly commissioned piece by Professor Emeritus Jackson Hill.

Despite limited rehearsal time, Hopkins says alumni arrived well prepared, blending seamlessly with students. “It was amazing to see everyone connect and make music together,” he says.

A Long-Awaited Induction

Fries pursued a master’s degree in computer science at the University of Washington, leading to a remarkable career that advanced the cause of women in technology.

In the June 4, 1979, issue of Computerworld magazine, an article titled “Women vs. Chauvinism: A DP [data privacy] Showdown” documented one of Fries’ quiet advocacy efforts. Frustrated by a clerical computing task she suspected was assigned due to her gender, Fries crafted a report deliberately using feminine pronouns to challenge the status quo. Her thoughtful approach blended technical expertise with a quiet stand for equality, leaving a clear message without disrupting her work.

Though Fries excelled professionally, she had yet to receive official recognition of her academic achievements at Bucknell. Tau Beta Pi began admitting women as full members in 1968 and extended an invitation to Fries in the early 1970s, but she was living in Seattle with young children and unable to attend the induction ceremony.

It wasn’t until the fall of 2024 that Fries received her due. She reached out to Bucknell with a simple request: Could she be inducted?

Thanks to the efforts of Erin Jablonski, director for the Perricelli-Gegnas Center for Entrepreneurship & Innovation, and Wendelin Wright, head of Tau Beta Pi at Bucknell and professor of mechanical and chemical engineering, Fries was formally inducted into the honor society. On October 6, she finally received her Tau Beta Pi pin — a long-overdue recognition for her academic excellence and an acknowledgment of her groundbreaking contributions to women in engineering and technology.

IN MEMORIAM

1946

Jean Brock Wallace, June 26, Whitehouse Station, N.J.

1947

1948

Peggy Rowe Harrison P’81, July 12, Rochester, N.Y.

Marion Rodan Steele, July 11, Willow Street, Pa.

1949

Marion Mayfield-Johnson, Sept. 23, Asheville, N.C.

1950

Lester Murray P’82, July 13, Anderson, Ind.

1951

1952

Josephine “Dodie” Hildreth Detmer P’76, P’79, Aug. 23, Cumberland Foreside, Maine

George “Bud” Keen, Aug. 16, Virginia Beach, Va.

Drew Seibert P’91, G’20, Aug. 23, Lakewood, N.J.

1953

Robert Cooper, July 16, Charlottesville, Va.

Mary Ann Fairchild Dilworth, Aug. 31, Pittsburgh

Lynn Gordon, Oct. 28, Ossining, N.Y.

Nancy Schreiner Hubley, Aug. 15, Harwich, Mass.

Edward Knorr, June 16, 2023, Indianapolis

Homer Middleton, July 29, Nashville, Tenn.

Jeane White Spoor, Oct. 16, Saint Johns, Fla.

Dolores “Dee” Staley Stover, Oct. 19, Pittsford, N.Y.

Michael Suber P’81, Nov. 28, Princeton, N.J.

John Troast P’79, P’85, P’87, G’06, G’08, Sept. 19, North Palm Beach, Fla.

1954

Theodore “Ted” Buley P’82, Oct. 4, New Paltz, N.Y.

Richard Kern, Aug. 8, Upper Saddle River, N.J.

Mason Linn, June 24, Frederick, Pa.

Vincent “George” McMann P’90, Oct. 25, Mendham, N.J.

Arthur Simon, Sept. 7, Suffern, N.Y.

1955

Claire Marshall McLean, Sept. 25, Shady Side, Md.

Susan Fleming Roberts, April 23, 2024, Audubon, Pa.

1956

Patricia Quinn Behre, July 13, Gettysburg, Pa.

John Hayes P’81, Oct. 26, Phoenix

Janet Pope Knorr, Aug. 15, Indianapolis

Ken Larson, Dec. 22, Montoursville, Pa.

Merrill Lynn, Nov. 3, Morton, Pa.

William Martens P’79, G’11, Dec. 4, Pownal, Maine

John McKee P’86, Aug. 29, Rockville, Md.

Floyd Naugle, May 12, Smith River, Ore.

PollyAnn Keller Owen P’81, P’84, P’86, G’22, G’28, Dec. 2, Trumbull, Conn.

Lorraine Soresi Tweed, Dec. 26, Richmond, Ill.

1957

Becky Cecil Brown, June 22, Baltimore

Carol Christ Steele, March 27, Jupiter, Fla.

Peter Tillotson, Aug. 31, Towaco, N.J.

1958

Robert Biglow P’91, Dec. 7, Naples, Fla.

George Brown, Aug. 22, Wernersville, Pa.

Ellen Campbell Champlin M’60, P’94, Sept. 19, San Francisco

Gail McMullen McCain, Nov. 13, Stowe, Vt.

Norma Jean Renninger Reed P’84, P’97, July 10, Lewisburg, Pa.

Merrett Stierheim, July 7, Pinecrest, Fla.

Corbin Wyant, July 2, Naples, Fla.

1959

Fredric Campbell, June 26, Milton, Pa.

Helmar Nielsen, Nov. 20, Saint Petersburg, Fla.

Gregory Ogden, June 16, 2023, Tampa, Fla.

William Sharkey, June 29, Midlothian, Va.

1960

Charles Devereaux P’85, July 11, Scott Township, Pa.

Richard Goeller P’91, P’98, June 25, Towson, Md.

Edward “Ted” Treadwell, Oct. 26, Blowing Rock, N.C.

1961

Jane Krimsley Matcha P’85, Sept. 16, Sugar Land, Texas

Isabel Fleming Millward, July 6, Seneca, S.C.

Lynne Pawlitz Pennell, Nov. 7, Jacksonville, Ill.

Lawrence Rajnik, July 8, Corning, N.Y.

1962

Deanna Rosen Gerber P’90, July 22, Stamford, Conn.

Diane Bowles Pucko, Nov. 14, West Chester, Ohio

Patricia George Scolaro, Sept. 5, Syracuse, N.Y.

1963

Mark Kaplan, Sept. 24, Branford, Conn.

Clement Noble P’95, July 21, Wilmington, Del.

1964

Robert Dretar P’89, P’94, G’22, Dec. 20, Vestal, N.Y.

James Hicks, Aug. 6, Stokesdale, N.C.

Nancy Talbott Iak, Sept. 19, Franklin, N.C.

John Tozier, Oct. 10, Greensburg, Pa.

1966

Constance Timm, Dec. 12, Lewisburg, Pa.

1967

Matthew McMonigle, Sept. 19, Ashland, Va.

1968

George “Doc” Roenning, Oct. 19, Sevastopol, Wis.

Robert Vater, Dec. 10, Greenville, N.C.

Richard Wildonger G’28, July 12, Landenberg, Pa.

Susan Foster Willett, Dec. 30, Stone Harbor, N.J.

1970

Gregory Bock, Dec. 9, Stratford, Conn.

Dennis Bradish, Sept. 14, Franklin, N.H.

George Warmath, July 11, Glen Allen, Va.

1971

Bruce Mortimer, Dec. 1, Lutherville, Md.

Paul Pickard, Sept. 7, Oak Bluffs, Mass.

Phil Reese, May 31, Leesburg, Ga.

Pamela Sprenkle, Aug. 21, Valentine, Neb.

1972

Thaddeus Prusik, Aug. 2, Stroudsburg, Pa.

1973

FRANK SAWICKI P’95, Dec. 28, Atlas, Pa.

1974

Robin Hummel Kenner P’03, P’08, Dec. 13, Allentown, Pa.

1975

1976

1978

1979

1980

Steven Young, Sept. 15, Sayville, N.Y.

1981

1983

1984

1985

1990

1991

1993

Kevin Kane, Aug. 12, Easton, Pa.

1996

2003

2009

2010

2018

2028

Master’s

William Bosso M’64, Aug. 1, Macungie, Pa.

Paul Farnsworth M’54, Sept. 19, Elysburg, Pa.

Norman Foster M’03, Oct. 20, Selinsgrove, Pa.

David Green M’62, June 1, York, Pa.