Indigenous

Origins

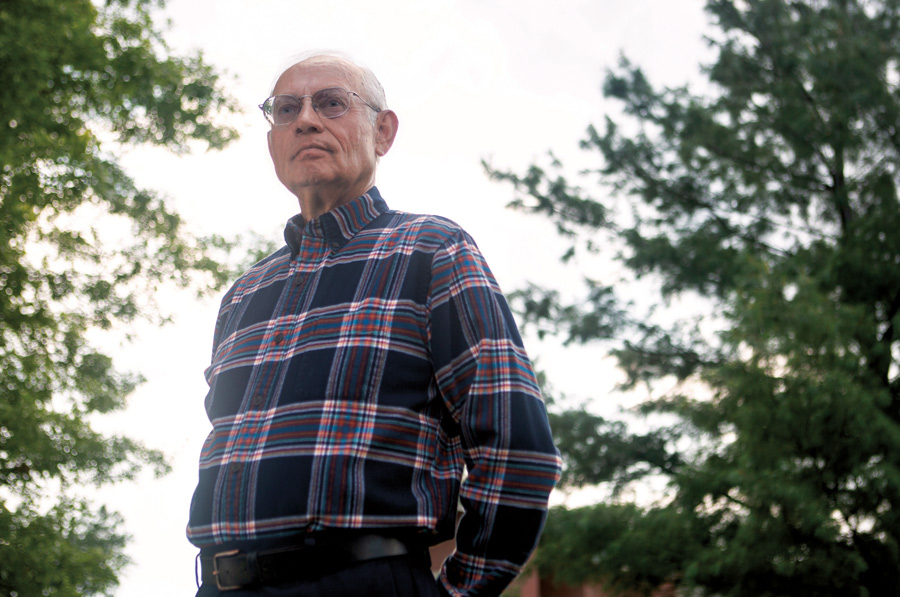

Photograph by Dustin Fenstermacher

Indigenous

Origins

Photograph by Dustin Fenstermacher

He has shared his fervor in a variety of Bucknell classes for years, including those taught by Professor Ned Searles, anthropology, and Professor Ben Hayes. As director of the Watershed Sciences & Engineering Program of the Bucknell Center for Sustainability & the Environment (BCSE), Hayes is on a mission to connect students with the original inhabitants of the land that their residence halls, classrooms and playing fields now occupy. Often, his lectures are delivered canoeside, as he and students paddle on the Susquehanna.

“As we drift in the current, we talk about the legacy of Native Americans in the Susquehanna Valley and their presence here today. It is important that students learn from their Indigenous stories and teachings, especially about matters of environmental stewardship, sustainability and governance,” Hayes says.

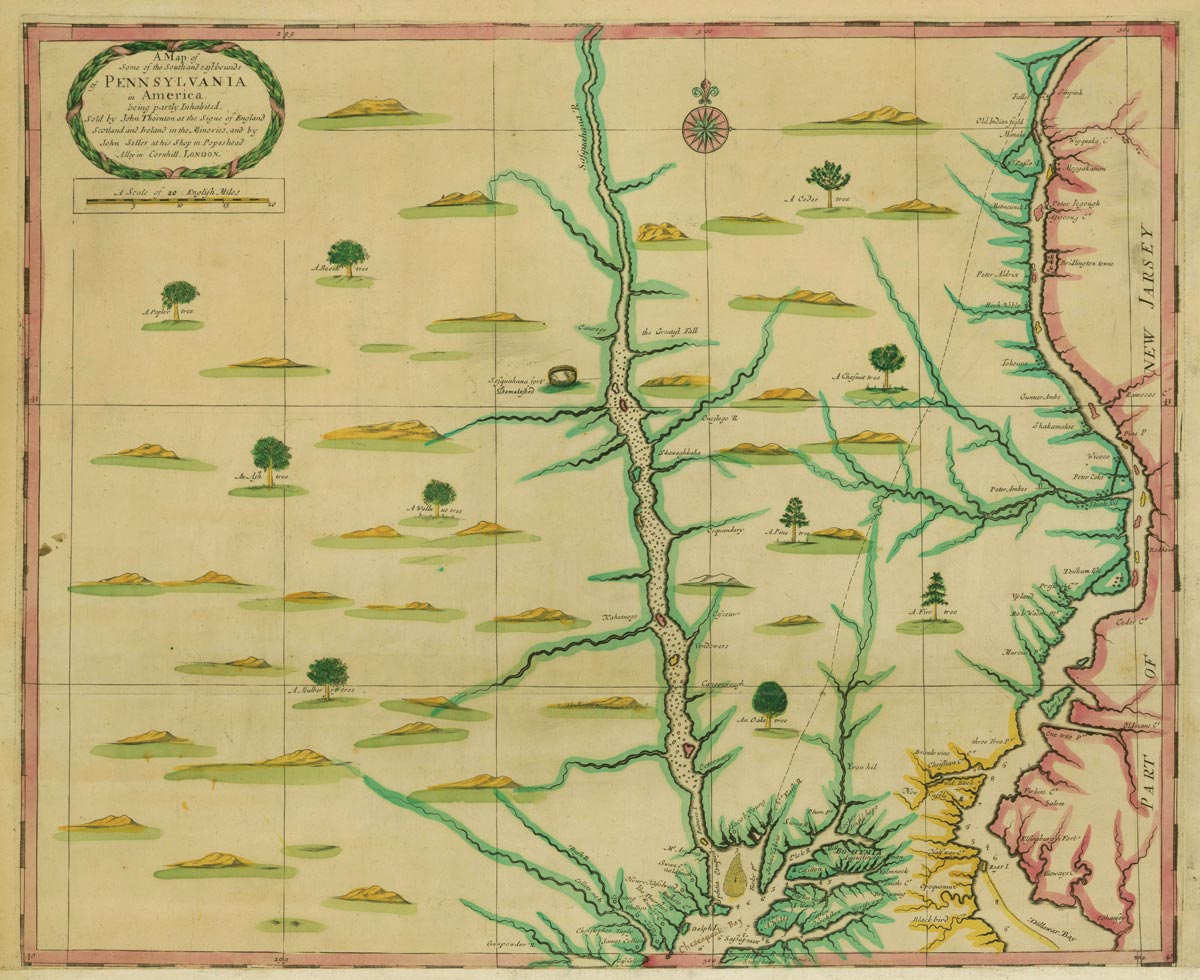

“Many are surprised to learn that Bucknell has a rich, rich legacy of Native Americans, extending as far back as 16,000 years ago, when small bands of Paleo-Indians began moving into the region,” Hayes says. “By 900 B.C., the population of native peoples increased greatly, so that by the late 1500s, the Susquehannock had permanent settlements in the river valley.”

EVIDENCE OF EARLY INHABITANTS

Barba’s history department colleague, Professor Claire Campbell, points out that “the most important thing to recognize is that these lands and waters were occupied by numerous Indigenous peoples at different points in history. Our current demographic and cultural landscape is a product of the conflicts of the past several centuries, and relationships between Indigenous and settler peoples have a place in all sorts of questions, from property rights to the way we tell history to environmental health and well-being.”

Campbell, who like Barba includes Native American content in all her classes, confirms that the Susquehannocks most certainly lived in the vicinity of Bucknell, but in the late 1700s they were decimated by infectious disease and white settlers’ encroachments on their land. In addition, she says, “The ascendant political power of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy, meant that many of the Susquehannocks were adopted into the Confederacy.”

“This area for us [Haudenosaunee] was used primarily for hunting and fishing, as well as trade,” says Jamieson, who hails from western New York. “Trade was huge at the confluence of the West Branch and the North Branch [of the Susquehanna] in Sunbury. That was an enormously historical meeting place for all of the Indigenous people, whether you were Delaware or Susquehannock. It was a metropolis, with several trading paths meeting right there. Using the Susquehanna River and its tributaries, you can get to the Chesapeake Bay and then the Atlantic Ocean.”

Like Jamieson, Hayes marvels at the superhighway-like status the Susquehanna sustained during the precolonial and Colonial eras. “In fact, two major paths went up both sides of the West Branch of the Susquehanna, with the Great Island path going right through Bucknell’s campus, on the west side of the river valley, near where the University’s river landing is located,” Hayes says. “There were footpaths for travel and trade routes for commerce, with wampum — shell beads used for currency and ornaments — flint tools, food and fur pelts moving north and south.”

A WOODLANDS CAPITAL

Not only did Native Americans live in Shamokin/Sunbury, 10 miles from Lewisburg, but they coexisted peacefully with settler colonists in the region for about 20 years in the mid-1700s, Faull says. Her forthcoming book from the Pennsylvania State University Press, The Shamokin Mission Diaries, translates from the German-language diaries of Moravian missionaries who lived in Sunbury in the mid-1700s.

“One reason reviewers said the book is important is that it shows how a third way was possible for Pennsylvania’s Colonial powers,” Faull says. “One way was for native people to retain sovereignty over their own land. The other way was the sovereignty of the settler colonists. For a brief period, there was negotiation and respect.

“And then what happens in the mid-18th century, in the wake of the French and Indian War, is this increased racial tension along the river, which fed massacres,” she continues. “Historians have been looking for a different way that the settler colonists and the native peoples could have lived together peacefully, and what happened right here [the friendly Moravian and Indigenous relationships] is one example.”

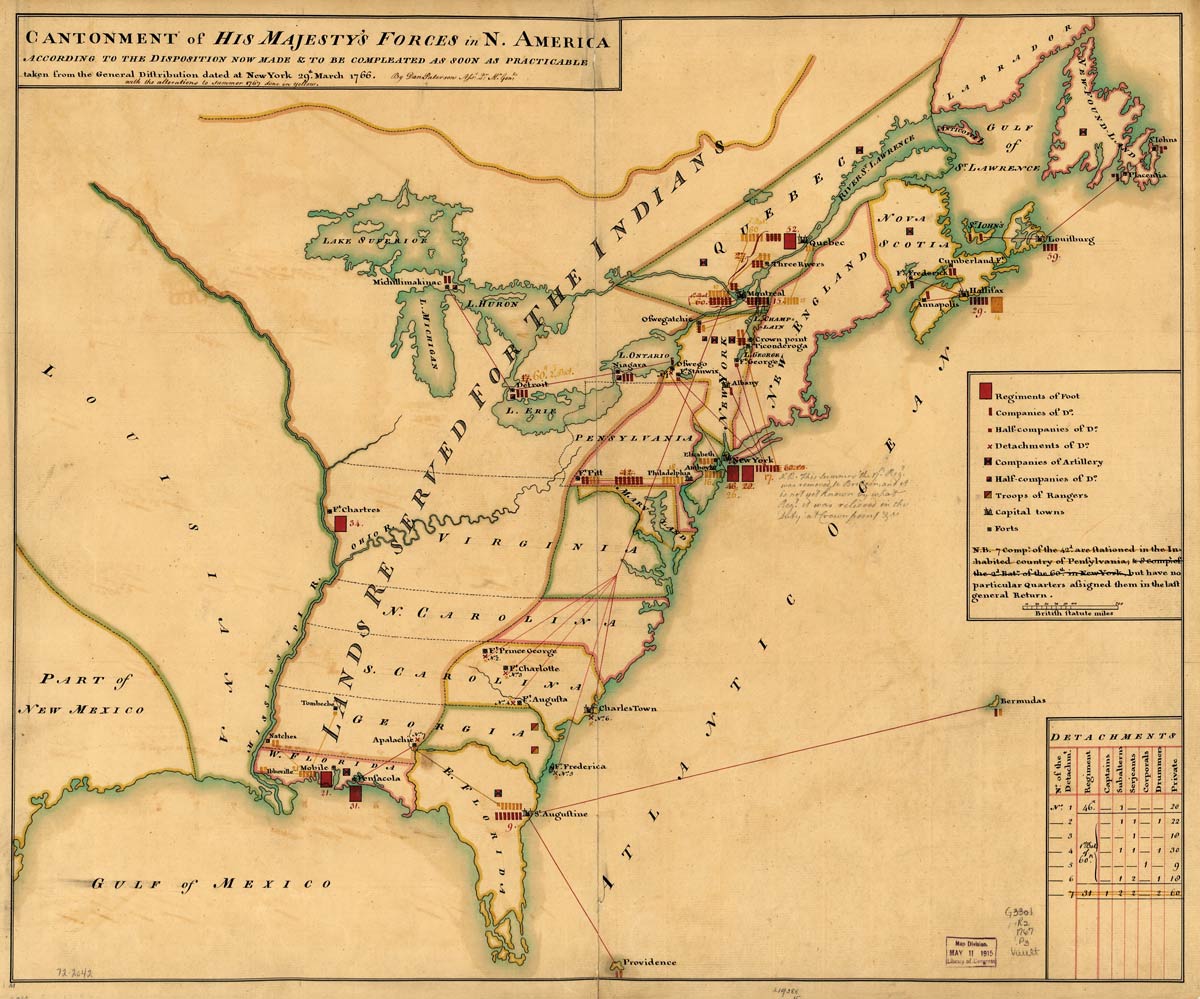

There were other peaceful and productive meetups, as in 1744, when the leaders of the Colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia met with the Iroquois in Lancaster. According to Jamieson, “the Iroquois sent a contingent of representative chiefs to the meeting, using the Susquehanna River to travel there. The head chief [Canassatego] told them, ‘If you don’t form a union like we have, you’re going to wind up fighting among yourselves.’ When the European people came here, they had little idea of how to form an inclusive government structure of the people, by the people and for the people.”

A MODEL FOR THE UNITED STATES

Despite the positive influence Native Americans had on the nation’s foundational principles, the relationship was not beneficial to Indigenous peoples.

Conflict between Native Americans and colonists along the western edge of the 13 Colonies grew in the years before the American Revolution, Campbell says. Issued by King George III, the Proclamation of 1763 was meant to check the encroachment of settlers on native lands, but the proclamation ended with the defeat of the British.

“We’re a living artifact of that,” Campbell adds. “We have to think about the stories we’ve inherited and how they’re framed. If we talk about central Pennsylvania as a ‘frontier,’ that suggests it was unoccupied; if our historic plaques talk about raids on pioneer homes during the Seven Years’ War or the American Revolution, we’re not asked to think about who was occupying whose land.”

As more whites arrived, the settlers became more powerful — and in some cases, violent. “Susquehannocks faced an unprecedented wave of violence, and many found themselves enslaved and trafficked across the Americas,” Barba says.

So where did the Native Americans go?

The Delaware, according to Jamieson, moved to Canada and Ohio, while the Iroquois primarily withdrew to their home territory in New York and Canada. However, not all of the Indigenous people left central Pennsylvania, says Faull. “There are still pockets of native populations throughout Pennsylvania, but because of racial politics, for the last 200 years they have been made invisible,” she says, citing the David Minderhout book Invisible Indians. “Usually, they passed as African American or stayed hidden in the woods, meaning they became backwoods people.”

THE INVISIBLE INHABITANTS

Bottom line, she says, is that “they weren’t all forced out West or decimated. Some people stayed, and it would be really wonderful to raise awareness of Native American populations right here.”

Faull has been instrumental nationally in highlighting the long history of Native Americans in central Pennsylvania. “About 10 years ago, a team of faculty, staff and students put together a really compendious report for the Department of the Interior, which looks at the history of native populations along the Susquehanna River,” she says.

The report, as well as efforts by Faull, Jamieson and Professor Paul Siewers, English, to partner with leaders of the Haudenosaunee, made a compelling case for the extension of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail to include the Susquehanna River. This first national water-based trail begins at the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and now extends 3,000 miles, to Cooperstown, N.Y., thanks to the extension granted in 2012.

With the help of interns, including Emily Bitely ’11, Faull developed a multilayered digital map of the Susquehanna River area as a supporting document for the trail extension. Bitely says the map displays Native American and historic sites along the river, using Paul Wallace’s Indian Paths of Pennsylvania as a main source.

“Many of the paths follow modern roadways, per Wallace,” Bitely says. Of the map, which can be found at go.bucknell.edu/SusquehannaMap, Bitely says, “It was so cool to take this piece of history and then put it into a modern context and make it accessible.”

The map, Faull says, is “an amazing resource for my classes, but it’s also been used by other scholars and even in a colleague’s book.”

A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT

Native Americans have a standing invitation to participate, and many members of the Haudenosaunee Nation have been keynote or plenary session speakers, Hayes says. The latest symposium, held in November, featured Dave and Wendy Bray of the Seneca Nation, who discussed the heirloom Oneo-gen white corn they cultivate on their farm in western New York.

While the symposium shines a light on Native American contributions to the natural world, so do the Bucknell Farm and Lewisburg Community Garden. Jen Schneidman Partica, farm & garden manager; Mark Spiro, farm faculty director; and a team of student farmers are looking to Indigenous people as models for sustainable agriculture practices.

This past summer, with support from a Bucknell grant underwritten by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Partica and six students researched Indigenous farming methods. “One famous practice by the Haudenosaunee people who were around this region is planting the three sisters — corn, beans and squash — together.” Doing so not only provides a greater yield, “but it’s better for the soil,” she says. Partica plans to start a three sisters practice at the farm this spring.

“Another thing we do is cultivate more areas of the farm with grasses and wildflowers that are native to the area,” Partica explains. “They provide a habitat for a lot of beneficial pollinating insects as well as insects that eat bugs that would otherwise eat our crops. We’re thinking about the Bucknell Farm as part of a bigger ecosystem. That’s a really common thread through a lot of Indigenous agricultural practices.

“The students have made a really good start with learning about these sorts of things,” she says. “But we’re really at the tip of the iceberg in terms of thinking about how we can build from Indigenous practices and start applying them here at the farm.”

A DECIDUOUS RECOGNITION

The Iroquois Nationals lacrosse team, which visited to play Bucknell’s team, coached by Jamieson, presented the tree. The white pine, Jamieson says, symbolizes friendship and peace. “The tree’s roots are the symbolic outreach of the Iroquois people.”

If you leave the Tree of Peace and walk up Moore Avenue to Seventh Street, you’ll encounter another tangible recognition of Iroquois beliefs. Adjacent to Taylor Hall is the Seven Generations sculpture, comprising stylized human figures cut from a single piece of steel.

Professor Mary Evelyn Tucker, East Asian studies, and her students spearheaded the effort to bring a replica of Frederick Franck’s sculpture to campus “as a symbol of hope and the generations to come,” as Jennifer Hunt ’93 wrote in The Bucknellian in 1992.

Franck was a Netherlands native who grew to appreciate humanistic subjects rooted in the environment. His inspiration for the sculpture was a law of the Six Nation Haudenosaunee (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Tuscarora and Seneca) Confederacy.

The Seven Generations sculpture has a controversial history.

A SIGNIFICANT SYMBOL

At the sculpture’s February 1992 dedication, Larry Shinn, then vice president of academic affairs, said the significance of the sculpture “is that it will stand for many generations of Bucknell students as a reminder of a native people’s concern for a long-range ecological vision our industrialized world must heed if it is to survive its own materialistic excesses.”

From the outset, the sculpture has been a controversial presence on campus. The seventh figure in the sculpture, a fetus, and an explanatory plaque were stolen soon after the original dedication. The fetus was returned to its place shortly after, and the sculpture was rededicated in a November 1992 ceremony led by Lyons, the faithkeeper of the Wolf Clan of the Onondaga Council of Chiefs.

Shaunna Barnhart, director of the BCSE’s Place Studies Program, says the sculpture is an important symbol on campus that has often been misunderstood as well as deconstructed. Other pieces have disappeared and been returned over the years.

“I’ve heard from some folks on campus that they don’t actually believe it was meant to represent the Haudenosaunee idea of seven generations and decision-making,” she says. “In my dream world, there would be an interpretive kiosk that explains what it represents, its contentious history and how that places it in this contemporary moment with sustainability and climate change.”

A Point of Pride

Having Native American ancestry is a point of pride for Smith, a 30-year-old Community College Scholar and psychology major from Orrtanna, Pa. That she is the only undergraduate who self-identifies as Native American surprises her.

“For this level of an institution and the grace that it has, I would have assumed that, with all of its other amazing philanthropic work and outreach, Bucknell would have been a little bit more targeted to bring in those kinds of voices and perspectives,” she says. “I was a little disheartened to hear that I was just one student.”

She was pleased, though, when, during summer RA training, the residence life staff acknowledged that Native Americans once lived on the land that Bucknell occupies. “We talked about the Susquehannocks who lived here, but not in depth.

“While you can’t change the fact that the land was taken from the people, you can acknowledge what happened and recognize that [the University] got to this point today because of these other people,” Smith says. “It’s not exactly reparations, but it was nice that the land acknowledgement was there.”

ACKNOWLEDGING ORIGINS

“Often we don’t talk about the transition of lands, and some of our most premier institutions are built on land that belonged to native people. It’s important that we get in the habit of acknowledging that, to give voice and visibility to those communities. It is also a way to force us to reconcile what our history has been — particularly a history of oppression.”

Nikki Young, Bucknell’s associate provost for equity & inclusive excellence and associate professor of women’s & gender studies and religion, agrees. “The history of how that transition of land happens is ugly, cruel, violent and tragic. Part of our responsibility, especially as an educational community, is to acknowledge that those things happened, and acknowledge that they did so as a result of colonization and genocide.

“One of the ways we can properly steward the land that we occupy right now is to educate on the past but also educate for the purpose of making the world a better place and ethically engaging the context in which we work,” she continues.

Currently, Young and others pursuing diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives on campus are developing an official land acknowledgment for the University. While many faculty and staff include land acknowledgments with their email signatures or as slides at the beginning of presentations, there has not been an approved Bucknell statement.

Knowing there’s an official acknowledgment in the works pleases Hayes, who honors Native American perspectives not only through the River Symposium but through information he imparts as he canoes with students down the Susquehanna, a feature of many of his Bucknell courses.

“How fortunate we are to be on ground that is sacred to the Native Americans, who teach us how to view the Earth in a holistic view and see the interconnectedness of all things,” he says. “We have so much to learn from their inquisitiveness, open-mindedness and ability to recognize patterns and infer things from the natural world. The legacy of Native Americans is all around and within Bucknell, and it is incumbent upon each of us to look for it, to learn from it, and share it with our students and with one another. It enriches our heritage and gives Bucknell a deeper sense of purpose and mission.”