Has Not

Erased

photographs by Andreas Krueger

photographs by Andreas Krueger

ith an autumnal chill in the air and a sense of anticipation written on our faces, the Bucknellians in World War I research team set out for the first task on its second commemorative trip. Our destination: the Henri Rollet Association, now called ESPEREM after recently merging with another organization. The new name — a play on the French words mère (mother), père (father) and espoir (hope) — reflects the changes within the organization, as well as ESPEREM’s goals of providing shelter to young, at-risk women.

On ESPEREM’s leafy Paris campus stands a building that memorializes Katherine Baker, Bucknell Institute, Class of 1892, a World War I nurse who helped found the organization 100 years ago. Over tea, coffee and pastries, we discussed with ESPEREM’s leaders our desire to keep this connection alive by installing a pedagogical garden where the girls can learn to grow their own food. Baker’s impact on the young women seems to only grow with time. When I noticed her portrait, which we gifted during our first visit in 2017, the president of ESPEREM’s board of directors, Véronique Goupy, told us that it’s good for the girls “to have someone they can look up to, a woman, someone they can relate to.”

In stark contrast to ESPEREM were the spaces we later encountered. For some — Julia Carita ’20; professors David Del Testa, history, and Adrian Mulligan, geography; and me — this second trip provided a fresh perspective on a familiar experience. For others — Peter Stokes ’21, Danny Collins ’21, John Slosar ’20, Patricha Williams ’19, Brig. Gen. (ret.) J. Ronald “Star” Carey ’61, Associate Provost for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Georgina Dodge, and professors John Hunter, comparative humanities and film/media studies, Keith Buffinton, mechanical engineering, and Mark Sheftall, history — this was a first exposure to the people and places Bucknell has been working to commemorate for five years.

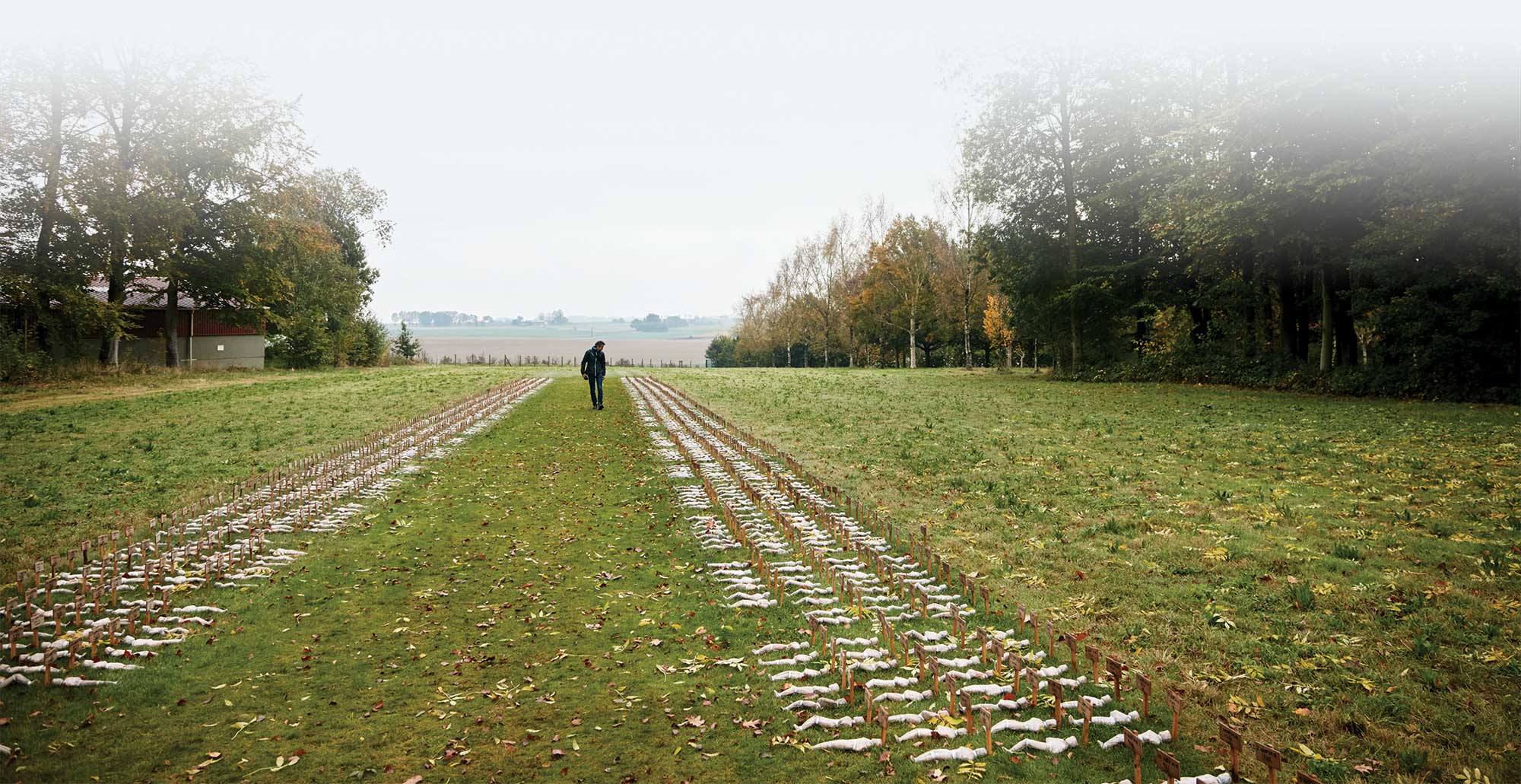

For the second time, we visited the burial sites of Bucknellians interred in cemeteries abroad. These military cemeteries are always striking, so calm and so quiet that the soft tick of sprinklers maintaining the immaculate grounds stands out. However, these beautiful spaces are reminiscent of a much uglier reality. In the words of Carey, “[We saw] rows of white marble stone markers, which then became acres of memories — and of dreams denied to their occupants … Everywhere there were mere teenagers whose stopped hearts became a parent’s broken heart.”

Though the cemeteries seem to be frozen in the past, other sites could not escape the changes that come with 100 years of existence. Battlefields that were once vast expanses of wasteland are now fields of thriving crops ready for harvest. Craters from shell explosions and mining warfare diminish as soil erodes, and etchings on less-prominent memorials have begun to fade in the absence of regular maintenance.

Despite the changes, time has not erased the marks of this conflict. Though slightly shallower now, the shell craters are still immense and easily convey the scale of the carnage that this war wrought. The web-like networks of trenches still run through the forests, and the remains of destroyed towns demonstrate the large swaths of land the men were expected to capture — and the comparatively small distances they were actually capable of taking. As Mulligan said, “These landscapes are speaking to you; they’re sending messages everywhere you look.”

Our espresso-fueled journey took us to many such places, each one as thought-provoking as the last. As we wandered through paths in the Argonne Forest — once the site of the deadliest battle in American military history — Hunter was struck by a thought: “If all of that energy had been constructive rather than destructive, imagine what we could have accomplished.”

In this time of remembrance, we must take care to remind ourselves that this is a war to commemorate, not glorify. As our team moves forward with this project, we hope to keep this in mind. Bucknellians in World War I started as an effort to remember our brave alumni and document their participation in a conflict that changed the world, and though it has grown beyond this, rediscovering as many of our Bucknellians as possible will always be our priority.