photographs by Dustin Fenstermacher

photographs by Dustin Fenstermacher

n a gray, rainy fall day, 14 Bucknell students make their way tentatively down a long white corridor, past a sign posted beside a security door:

If you have integrity, nothing else matters.

If you don’t have integrity, nothing else matters.

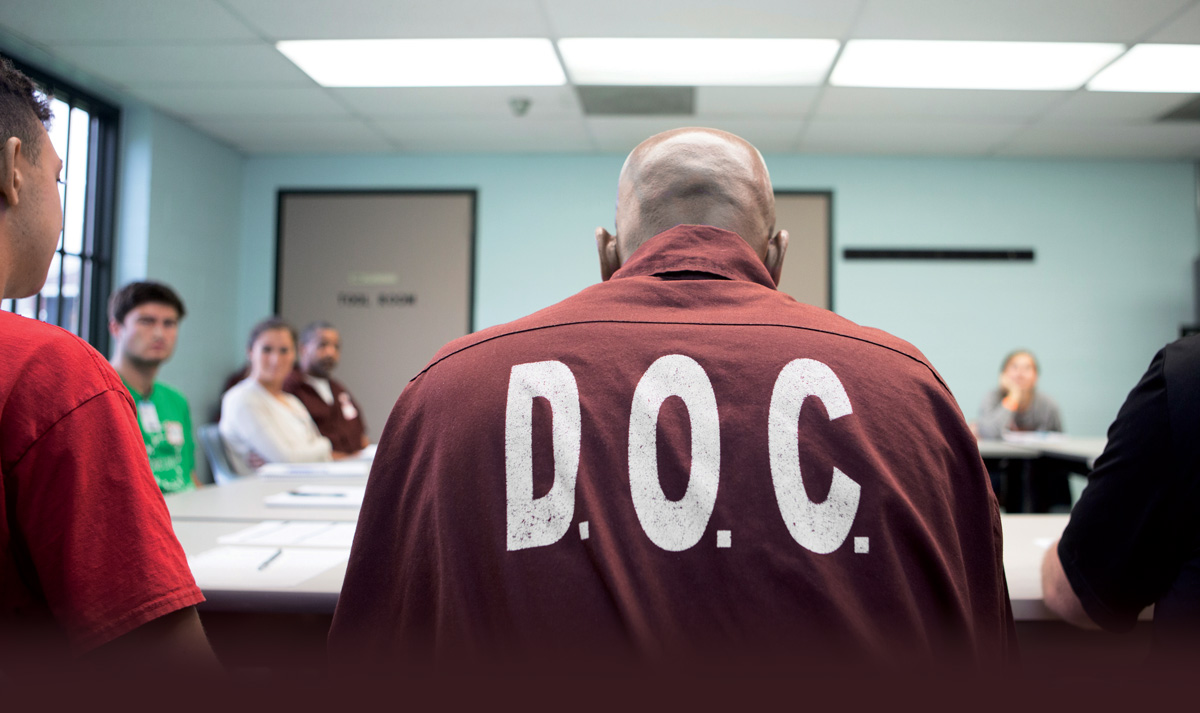

On their left they pass what looks like a high-school shop class — except all of the “students” working the machines wear brown uniforms with D.O.C. (for Department of Corrections) on the back. The Bucknellians enter what looks like a traditional classroom, with a desk near the door where a prison staffer sits, a blackboard and circle of desks. Seven men, wearing smiles and those same brown jumpsuits, extend their hands to welcome the students. Professor Carl Milofsky, sociology, who teaches this class at the State Correctional Institution (SCI) at Coal Township, 28 miles from Lewisburg, asks the students to sit between the men.

The students learn at the outset that these men love dogs for the comfort they give. Some have children. And grandchildren. And all, like Sam, whose impressive height, posture and hoary beard lend credence to his nickname, “the dean” of the group, have something else: a life sentence.

“My name is Sam, and I’m 50 years in jail. My major is freedom,” he declares, after the student to his left introduces herself as an animal behavior major.

Milofsky is the most recent Bucknell professor to offer a class through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, an endeavor pioneered by Lori Pompa at Temple University in 1997. In the last 20 years more than 35,000 “inside” and “outside” students nationwide have taken classes in a prison setting through the program.

Davis, who has taught the class 10 times, says, “It gives an adrenalin shot to the way I teach. I ask myself, ‘What pedagogy do I use in this situation?’ The teaching strategies I’ve tried out are things I’ve subsequently tried out for other courses I teach at Bucknell.”

The faculty director for academic civic engagement points out that one of the many ways Bucknell has supported the program is by purchasing textbooks for students on the inside. She holds up a copy of Women and Crime: A Text Reader, saying, “Whatever is written on these pages comes alive in the class. The statistics about the disproportionately harsh treatment of black women in prison, for instance, is borne out in stories shared by inside students. For the outside students, this humanizes the people who commit crimes. The takeaway for the Bucknell students is, ‘This could have been me.’ ”

That was precisely what Nadia Sasso ’11, an English and sociology major, thought as she sat in Davis’ Muncy classroom eight years ago. A child of African immigrants, Sasso is now pursuing a Ph.D. in Africana studies at Cornell University. Sasso was then a senior from the Washington, D.C., metro area who was able to attend Bucknell through the Posse program.

Most of the inside students in Sasso’s class were black or Hispanic, reflecting the racial composition of the five prisons in or near Union County, where Bucknell is located. Besides Muncy, there are two federal facilities, United States Penitentiary (USP) Lewisburg and USP Allenwood, which has three separate divisions.

“Until they took that class, they didn’t know how racism and sexism were impacting where they were at the moment,” Sasso adds. “If you come from a certain neighborhood, it’s hard to rise above. They educated me by being able to connect the dots for me.” The class has a lingering resonance for Sasso, as some of her family members are currently incarcerated.

“The Bucknell students self-report that it’s a pretty powerful course, where they use the skills they develop in class to be more thoughtful about how they are spending their days,” Daubman adds.

Brandon Williams ’15, an education and psychology major, was one of three men who took Daubman’s class in fall 2013. “I took things from [the inside students] that helped me,” he says. “We weren’t there to help or study them; we were there to learn with them. They still felt they were contributing something and took their work seriously. Seeing inmates doing their homework and doing a good job motivated me to keep up. Engaging in that class also gave me some tools to apply to the first job I had.”

After earning a master’s in addiction counseling from the University of Minnesota, Williams became a drug and alcohol counselor at the Carbon County Correctional Facility in eastern Pennsylvania. He spent two years there before recently taking a job with an inpatient drug and alcohol facility. Someday, he says, he would welcome working again at a larger facility. “I love working with that population,” he says.

According to Willeford, who came to Bucknell in 1950, “There was a time back in the ’50s when Lewisburg was a low-security prison, and prisoners who were close to being released were allowed to come to campus to take courses. Also, Bucknell professors would go out and give courses.”

One of Willeford’s favorite stories concerns Jimmy Hoffa, the notorious union leader who was sent to Lewisburg in 1967 to serve a 13-year sentence for involvement in organized crime.

Today, USP Lewisburg, a stately red-brick complex built in 1932, is a maximum-security prison. Bucknell professors no longer teach there, although some, like Willeford and Milofsky, have provided encouragement to inmates by meeting with them through the local Prison Visitation and Support program. Other Bucknell faculty and staff reach out to incarcerated persons through the Lewisburg Prison Project, a prisoners-rights organization founded in 1973.

Milofsky’s visits with incarcerated men at SCI Coal Township led him to take the 60 hours of training in Philadelphia required to teach classes through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program. Among the program’s requirements are that outside students dress modestly, refrain from exchanging contact information with inside students and not ask about crimes the insiders committed.

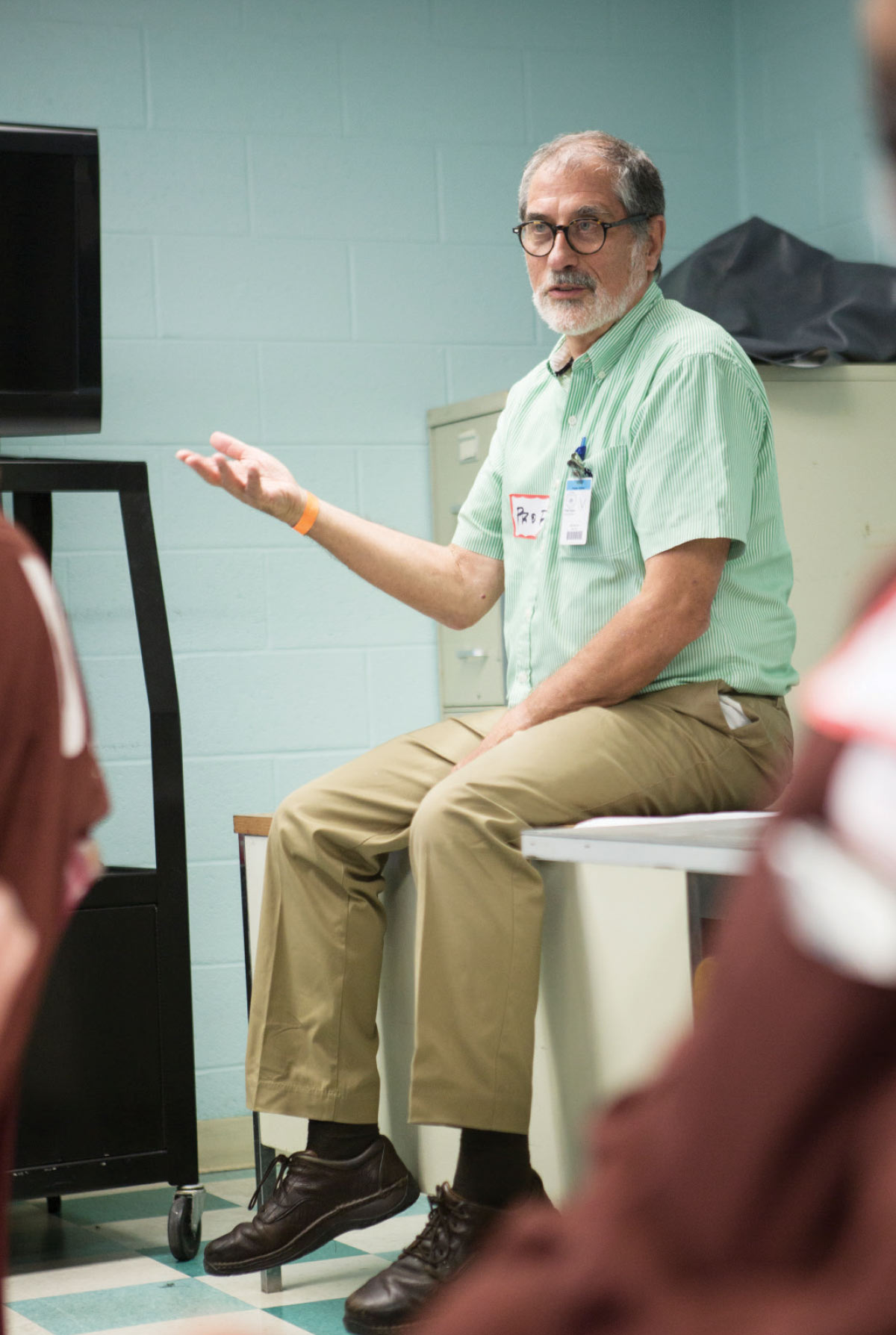

Milofsky, a trim man of 70 with bright blue eyes, has long been involved in the blighted coal region where the state men’s prison is located. Like several other Bucknell faculty members, he works with the University’s Coal Region Field Station in Mount Carmel, Pa., to improve the lives of the area’s residents, many of whom are struggling with opioid addictions and lack of employment.

Members of Lifeline, inmates who model good behavior and make positive contributions to prison life, raise money for charities and special causes by selling products and donating their profits. McGinley says he encouraged them to give their proceeds — $3,000 to the Bucknell-led athletics camps, held through Mount Carmel’s Mother Maria Kaupas Center, and $1,000 to the Mount Carmel Food Pantry that a Management 101 class reorganized to be more efficient.

“These are the sorts of things I want my inmates participating in,” says McGinley. “They want to be a part of the betterment of the community, and I think that’s what’s outside the public eye a lot of the time.”

Milofsky dipped his toe into prison teaching last spring when he offered his first prison-oriented course, Deviance and Identity. In that class, eight students traveled with him to SCI Coal Township to meet with Lifeline members, while four others went to another Lewisburg-area prison, the high-security division of USP Allenwood, which, like SCI Coal Township, opened in 1993.

“When I look back, that was by far the most difficult thing I’ve done,” says Jordan, a former football player who is a political science and sociology major, a Bucknell executive intern and a Coca-Cola marketing intern for Bucknell Athletics. “It was one of my most rewarding experiences at Bucknell, and it sure makes for a great story: ‘I worked at a prison,’ ” he says with a smile.

At first, says Jordan, he felt intimidated walking into prison, but the incarcerated men “pulled up a chair for us. They made a conscious effort to make us feel comfortable. They were very intelligent; they just needed help with connecting the dots. We found ourselves learning from them.”

Jordan says most of the men he met at Allenwood were, like him, black. “We’re 13 to 14 percent of the U.S. population,” he says, while 38 percent of U.S. inmates are black, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. “This is indicative of unfair policing and so many of the broader sociopolitical and racial issues we’re experiencing in America right now,” Jordan says.

His experience in Allenwood, he says, “has made me think about working in the federal government toward educational reform.”

Lina Hinh ’19, another student in Milofsky’s spring class, joined the sociologist at SCI Coal Township, the medium-security prison where 2,400 inmates live. There she met Sam and David, two polite men who’d spent decades in prison for crimes committed in their youth and for which they had received life sentences without possibility of parole.

“The class opened my eyes to the falsehoods that a lot of politicians have said about people in prisons,” says Hinh, who wants to work in public policy to help victims of human trafficking. “Working with the prison group made me realize that I need to stay in this field. A lot of trafficked people end up in prison.” Being in the course, she says, “also made me realize the people in prisons are humans and not animals, which is how the media portrays them.”

Ella Ri ’19, an accounting & financial management major, says her fascination with the Netflix series Orange is the New Black “got me more interested. I don’t think TV accurately depicts prison life, and I wanted to learn what’s really going on. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I can take classes in a different area than my major, which is why I love the liberal arts.”

Virginia Whelan ’19 spent two summers working in a nonprofit for rehabilitated inmates. A history and sociology major, she says she wanted to “experience firsthand how people can change and to see them as humans even though they’ve done something wrong.”

Preparation for a future job counseling people with mental illnesses inspired psychology major Kelsey Birmingham ’19 to take the class. Her goal for the course, she says, was “to prepare me to work with people in high-stress situations.” For a required class project, where the inside-out students are divided into mixed groups of seven, she says, “I hope to come up with a plan to help with their rehabilitation when they get out.”

And they encounter Gary, the only white member of the inside group, who works in the prison library helping other men with their cases. He tells the students, “There are good people inside who made a split-second decision that brought them here.”

They meet Dave, who shares that “we don’t take time for granted,” and Craig, who notes, “as I do my time in here I start to reflect about all of the mistakes I’ve made.” Through his work with the Lifeline group, “I have the opportunity to repair what I have destroyed.”

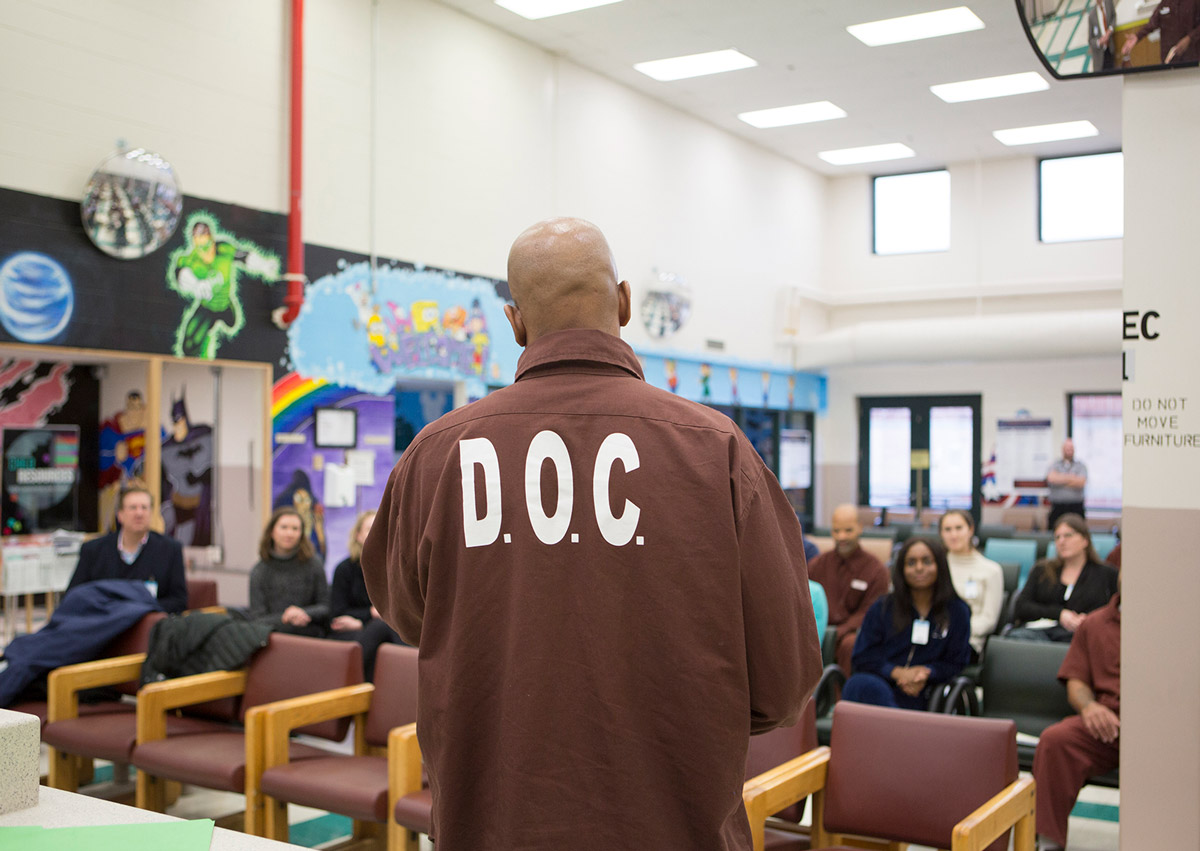

Dave, the most talkative of the insiders, articulates many of their feelings, saying, “We want to change your ideas about people in prison. We’re not all the same. You’ll see that on display here. But none of us have the mindset where we have given up. We still have a sense of life, a sense of self. In common, we all want to be free someday.”

My impression of the outside students was very favorable. This is due to the level of intelligence, maturity and sense of direction they displayed with their brief introductions. It was obvious that most, if not all, would be nervous coming into a prison for the first time, not knowing what to truly expect. However, it was evident that all of them seemed to relax a bit once they began to engage in dialogue and become aware of the fact that they were in a safe place with people that meant them no harm. I look forward to this semester, getting to know the students, learning from them and possibly teaching them as well.

— Anthony

We started our new class with introductions and opening statements by all the participants in the class. There were photos taken by Bucknell’s magazine, while the insiders answered questions from the outsiders about various thoughts they have in reference to the prison experience. The end of the class, or the last half an hour, was dedicated to answering questions for the editor of Bucknell Magazine.

The first class is always difficult, because people are trying to find a comfort zone in which they can engage each other. Insiders discussed many things like the current legislation being promoted to offer a form of relief to the prisoners serving life sentences, e.g. S. B. 942 by Sen. Sharif Street, and H.B. 135 by Rep. Jason Dawkins, and we talked about redemption, communal service and mentoring the younger prisoners in the institution. We emphasized the importance of making sound decisions in your life, because decisions can have long-range consequences that we must pay close attention to in order not to make the sort of mistakes that many prisoners have already made in their lives. There were many other questions asked and answered as the day moved along, and time was an issue, because we did not have enough time to discuss all the issues in a manner that would allow us to give the most clarity to the subjects.

The insiders also spoke about certain legal concerns like what a time bar is, and how such laws negatively affect us. We spoke briefly about the 13th Amendment and the detrimental consequences of that aspect of the Constitution. We spoke about how what most people see on television does not accurately depict prison life, because most people [in prison] are bored to death, more so than the exciting prison experiences shown in television programs designed to entertain, not accurately explain our existence.

Overall I feel as though the class went well and that we will ultimately be able to have some powerful conversations with the outsiders as we improve the class.

The thing that I really appreciated about the outside students is their profound interest in learning about the prison experience from a balanced standpoint, rather than just gathering information from the staff or nonprisoners. I say this because there is so much misinformation circulating in the public about the prison experience that would have people viewing us as a monolithic group, rather than people with different personalities and experiences.

— David

Concerning your comments about the inside students introducing themselves with reference to time, I have learned that time is synonymous with life. As long as you have time, you have life. When you run out of time, you run out of life. Prior to our arrest, time and life were something we took for granted. Since then, our acquired consciousness has engendered in us a healthy respect for two things we can’t do without — life and time. Introducing ourselves through the prism of time, we announce that we have/are keeping pace with life inside and out by being cognizant of the value of time, in spite of the obvious circumstances.

— Sam

This being my second go around with the inside-out experience, I expected to be fairly more prepared for meeting this group of outside students. I found myself feeling as if it were of paramount importance to create a quick, yet visceral connection between the inside and outside students. Humor being a commonly used method to connect people on equal levels, I attempted to bring some levity to our first group meeting, figuring that the added variable of having a photographer and journalist present might inhibit some of the outside students from sharing much. I was glad to see that even in our first class meeting some of the outside students began opening up and felt comfortable enough to share their perceptions with the inside students. I think that this will expedite the necessary bonding experience between inside and outside students that will facilitate a free-flowing, honest and even critical dialogue within the class.

I was surprised to witness the level of intelligence within these relatively young people. I consider it a great honor to be a small part of their learning experience, and I am grateful to learn with them.

— Tito

It was truly an honor meeting you and the students this past week. Naturally, when meeting people for the first time there is always a sense of uncertainty that arises in whether or not a person would be well received. This sense is even greater for those of us who are incarcerated, because of the stereotypes that usually influence people’s perceptions of us. But, personally, my impression of the encounter, in its totality, was one of appreciation, in one sense being from the number of students who showed an interest in wanting to participate. The second had more to do with me reflecting on the course on which my life has taken me, from being adjudicated by my peers for a civil infraction to now having the right state of mind to positively effect change in the lives of those seeking to find their way in life, personally, but also on a grander scale. It is the future generations we are able to share with in these settings, which is promising considering the fields that the students have elected to pursue.

For me this is the meaning of purpose.

— Daliyl