More than 700 Bucknellians served in the “war to end all wars,” fighting For democracy, justice and the rights of small nations.

A century later, a faculty-Staff-student initiative reconstructs the stories of those brave men and women.

More than 700 Bucknellians served in the “war to end all wars,” fighting For democracy, justice and the rights of small nations.

A century later, a faculty-Staff-student initiative reconstructs the stories of those brave men and women.

All black and white photos: David Del Testa

HOW IT GOT STARTED

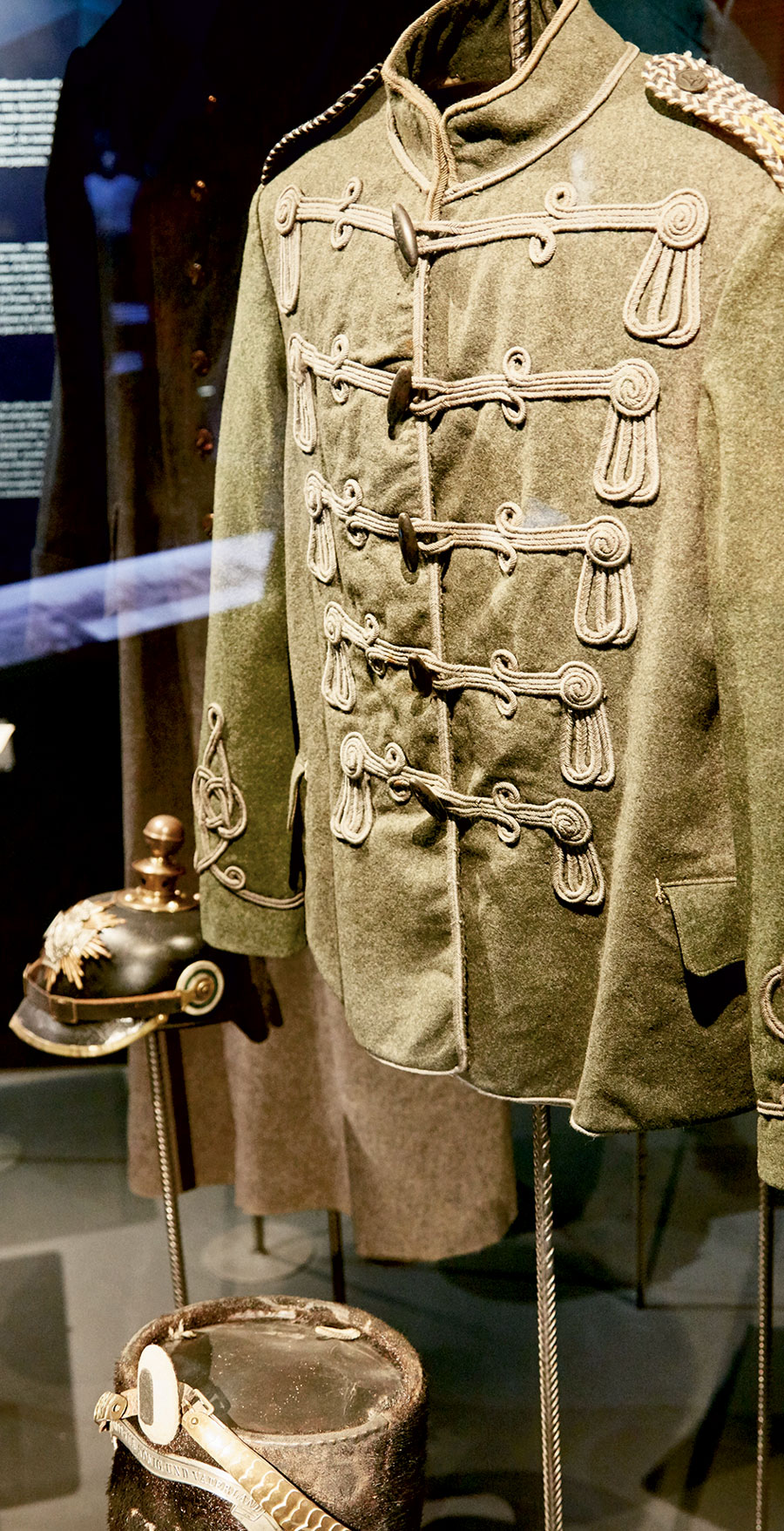

Professor David Del Testa, history, who teaches courses on World War II and the Vietnam War, was drawn to the topic after Isabella O’Neill, University archivist, described some items in her care related to Bucknell’s involvement in World War I.

WHAT’S NEXT

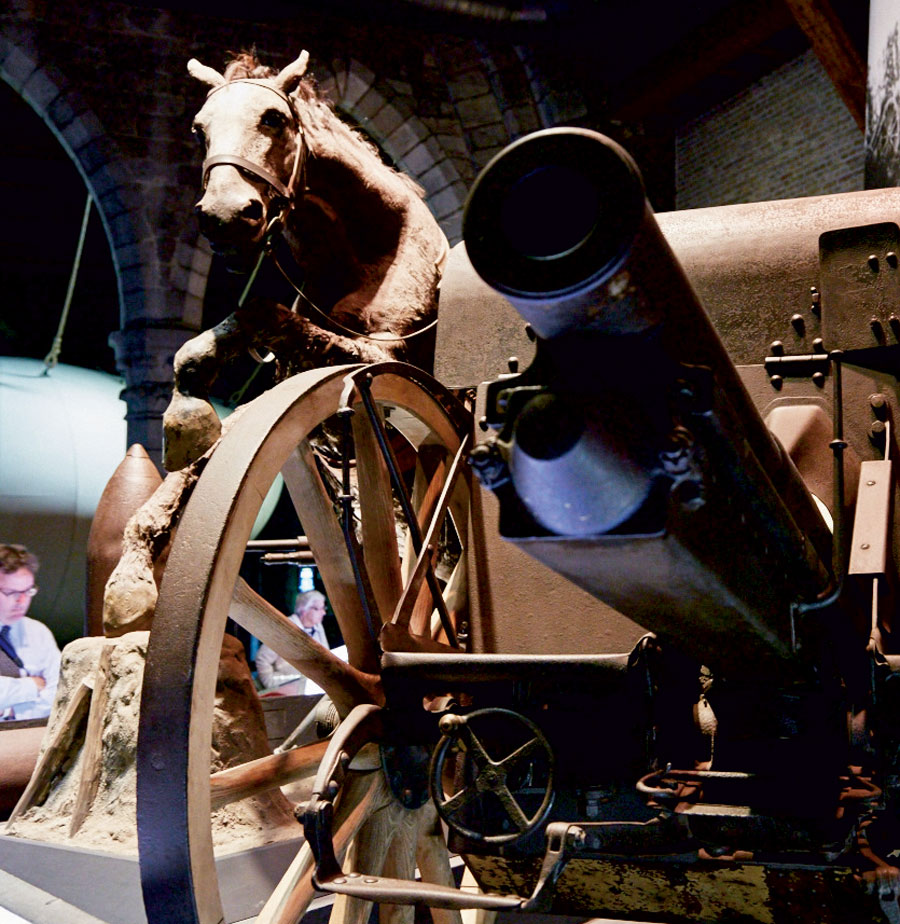

On top of its database of 717 alumni, the project has expanded into related research topics — from memorializing African-American vets to monitoring the war’s lingering environmental damage.

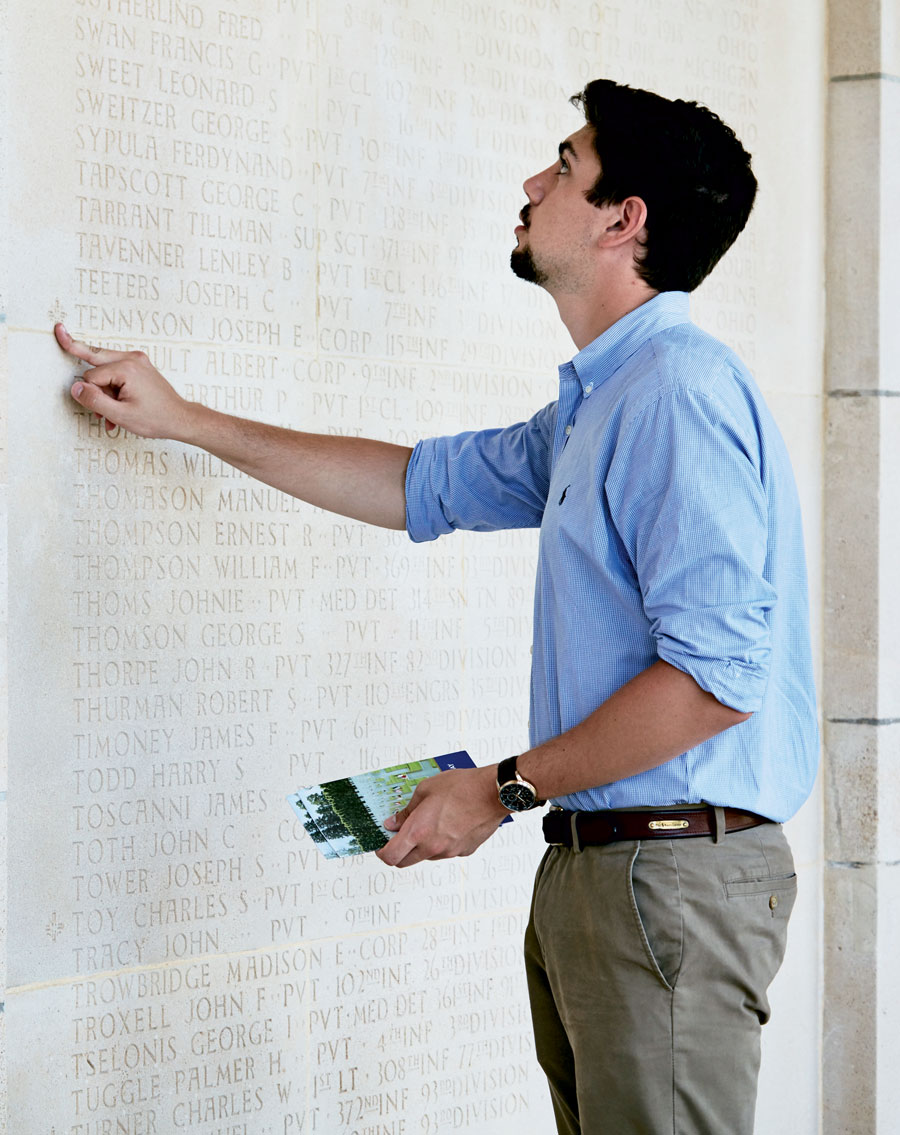

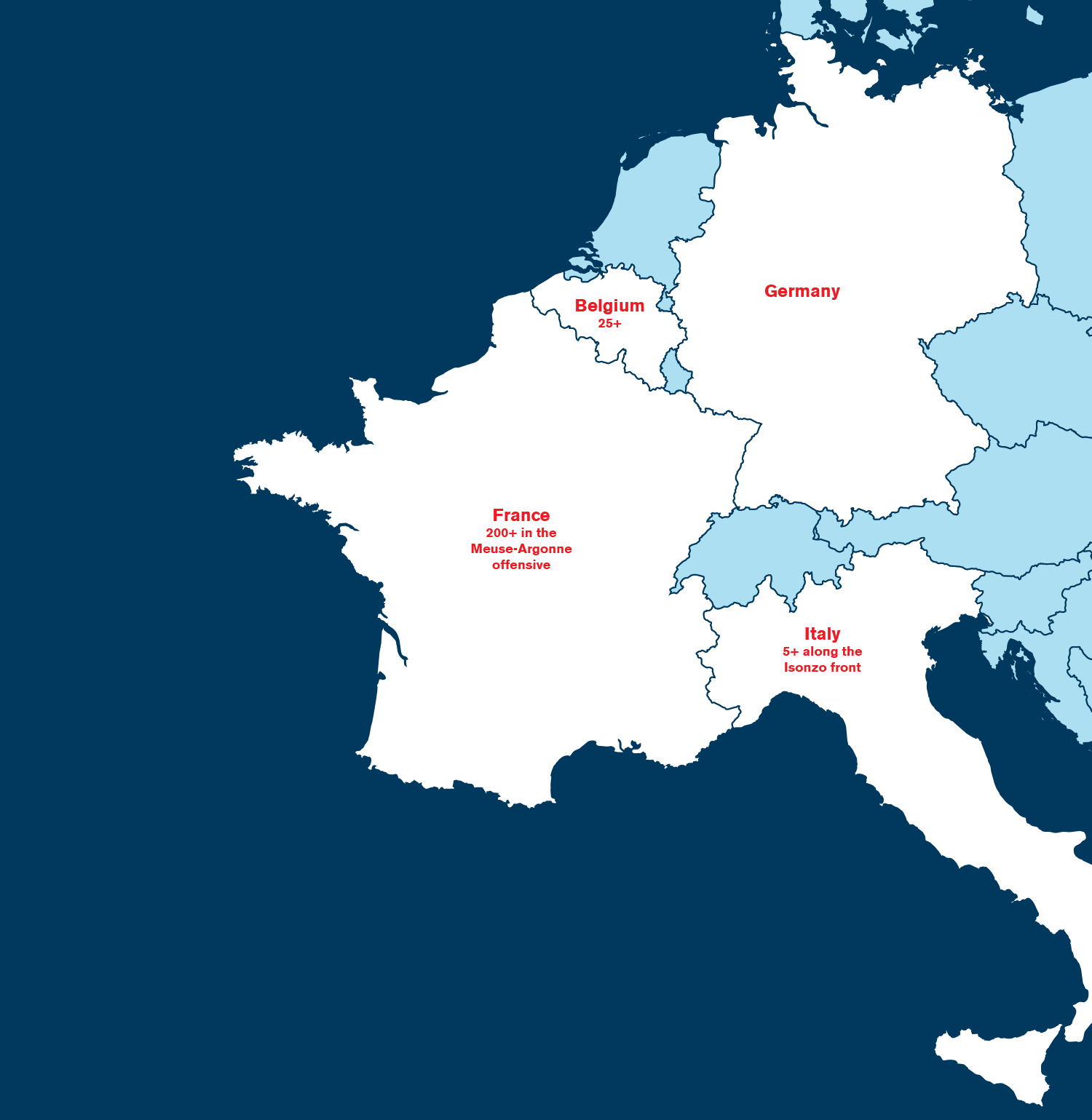

Bucknell senior A.J. Paolella, his 6-5 torso clad in a light blue, long-sleeved shirt and khaki pants, cut his way through an endless blur of white crosses and a few Star of David-adorned stones in the largest American cemetery in Europe on Memorial Day. Paolella glanced at the names and dates of death, all stretching back nearly a century, seeking two among 15,000 markers at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in eastern France.

Plot A. Row 16. Grave 26. Paolella pointed, and we stepped quickly but carefully, to avoid walking directly on the graves, making our way to 2nd Lieut. Baker Spyker, Class of 1922, of Lewisburg, killed less than a month before World War I’s bloody conclusion Nov. 11, 1918.

Maybe it was the heat (a brutal 96 degrees); maybe it was the fatigue (we had been bombing through rural France in our big blue bullet of a van for days); definitely it was the emotion (we had just heard “Taps” and the French and American national anthems played by the French Armored Cavalry band of Metz in a formal Franco-American ceremony), but our group of women and men, spanning ages (late teens to late ’50s) and origins (Pennsylvania, California, North Carolina, Ohio, New Jersey, New York and Ireland) found ourselves unified by tears and remembrance. Some imagined Spyker as a son, some as a boyfriend. Some, like Paolella, who had turned 22 a few days earlier in Paris, imagined Spyker as himself, had he been alive a hundred years ago.

“There you go, Baker,” Paolella said, as he laid a blue-and-orange Bucknell banner on the grave. In understatement, Professor David Del Testa, history, who’d spent the last three years preparing for this day, said, “I bet it’s been a long time since anyone visited you, Baker.”

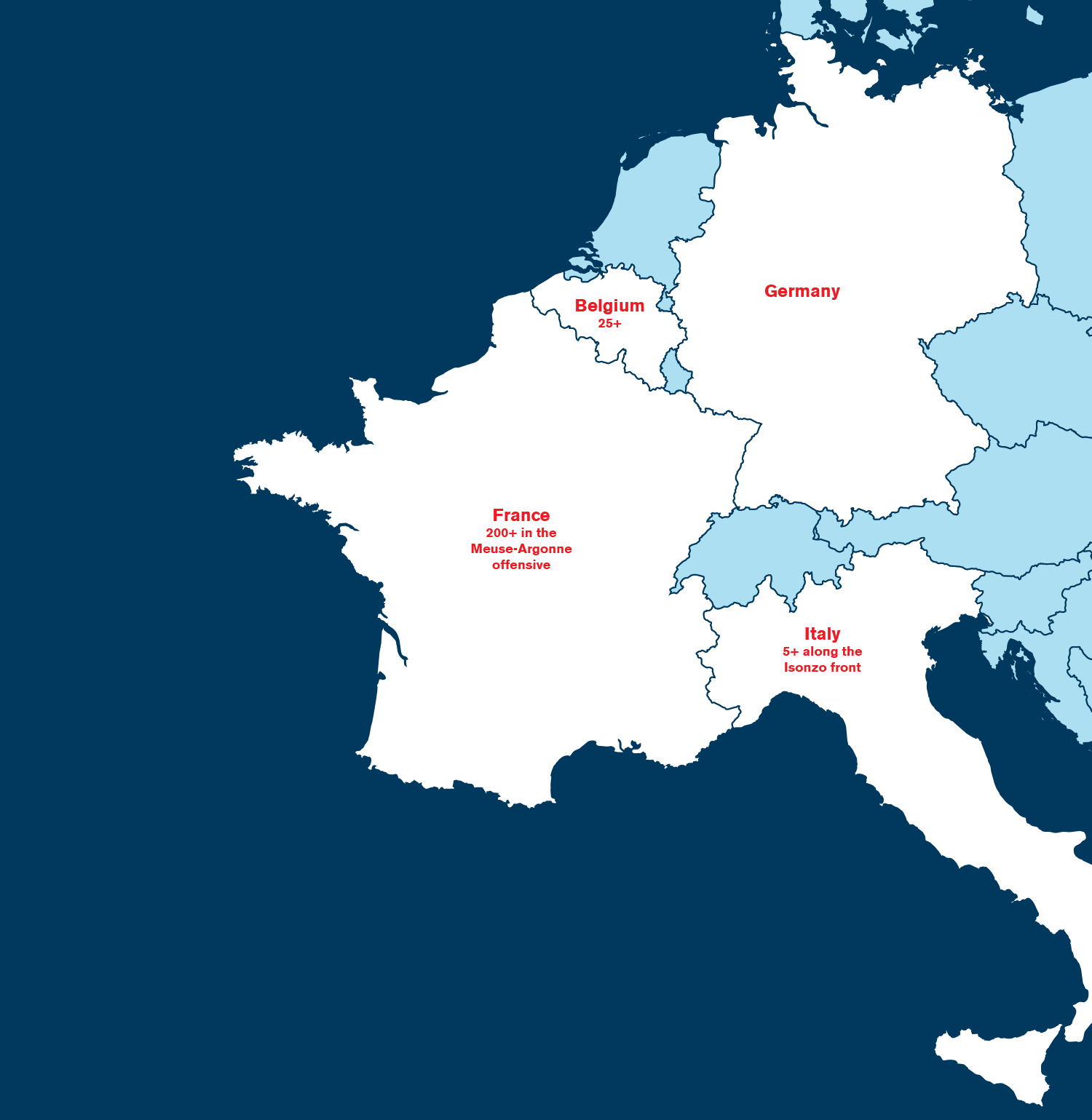

A few minutes later Paolella strode out in search of the second Bucknell grave. The group clustered at the headstone of 2nd Lieut. William Chalmers Acheson, Class of 1916, of Pittsburgh, killed just one day later than Spyker, Oct. 14, 1918. After Del Testa read an excerpt from Acheson’s Distinguished Service Cross citation, we placed another Bucknell banner between the French and American flags on his grave. Both men had fallen in the last great battle of World War I, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which claimed the lives of 26,277 Americans, the greatest number of any battle in our nation’s history of warfare.

Visiting Spyker and Acheson, and the next day, Charles O’Brien, Class of 1909, at the Aisne-Marne Cemetery, were the most emotional moments of our visit last spring to memorials and sites in France and Belgium associated with Bucknell graduates, most of whom were from Pennsylvania.

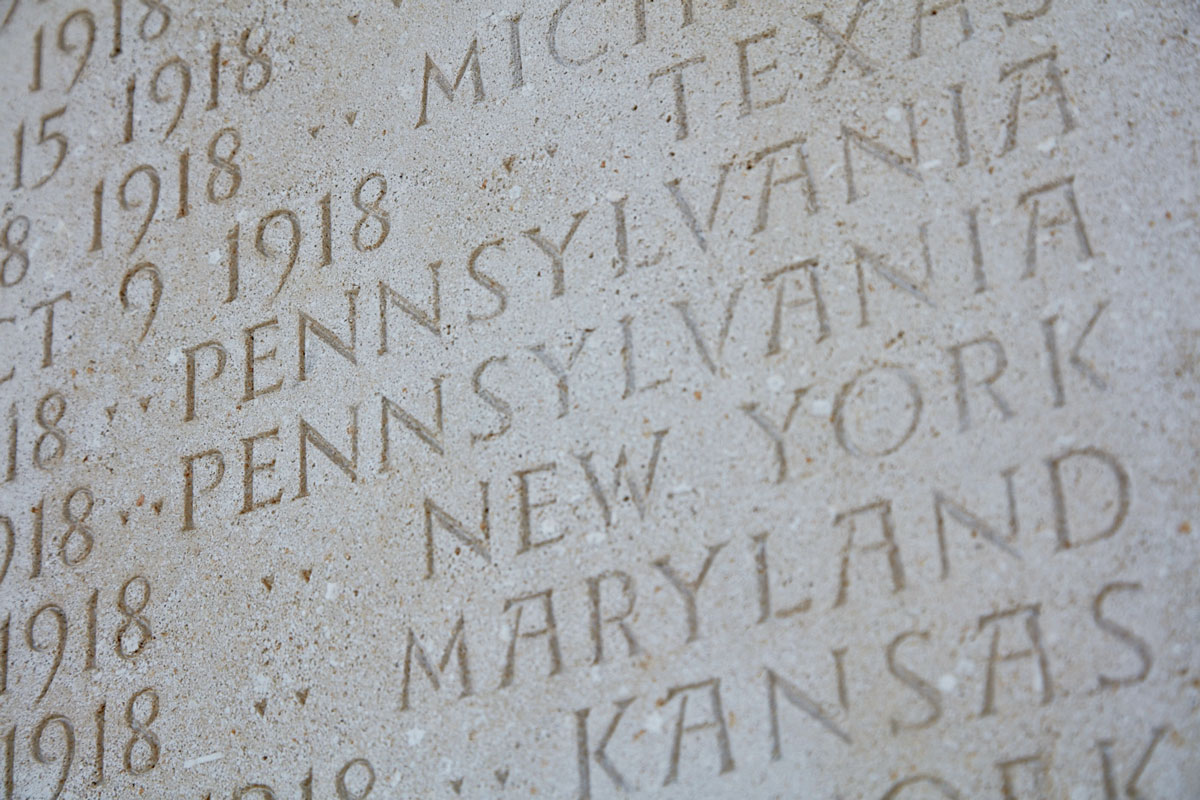

Pennsylvania is probably the most expressive state when it comes to commemorating its Great War veterans, as perhaps is Bucknell among universities, having dedicated resources and time to sending our research team abroad to locate and remember our dead.

Del Testa set out in 2014 to discover all of the Bucknell alumni who had served in World War I, whether as soldiers, nurses or ambulance drivers. He recruited a team of students — Paolella, Amy Collins ’18, Julia Stevens ’20 and Julia Carita ’20 — as well as Professor Adrian Mulligan, geography, and me to assist him in bringing some of the names in the database to life. Dante Fresse ’18 accompanied the group as documentarian.

A second research trip next October, just before the 100th anniversary of the armistice, will enable us to continue our research and expand the scope to include new partners and areas of interest that include memorials to African-American World War I veterans, the Oise-Marne Cemetery and the Somme battlefields. Completion of the database, a book-length manuscript about the project and a World War I history conference on campus are among the outcomes we envision in the year ahead.

The intent, says Del Testa, is to create a Bucknell history that doesn’t exist. “There were institutional changes made during the war to make the University more in line with its peers,” he says. After the war, “Bucknell becomes larger and more cosmopolitan [with veterans returning to campus],” he adds. Bucknell’s position today as a leader in higher education could be construed as a result of its more-worldy outlook, post-World War I.

United States

In San Juan, Puerto Rico

Bermuda

Russia

In Vladivostok, Siberia

United States

In San Juan, Puerto Rico

Bermuda

Russia

In Vladivostok, Siberia

June 28, 1914

- Heir to the throne of Austro-Hungary assassinated by Serbian nationalist

July 28, 1914

- Austro-Hungarian Empire declares war on Serbia, starting war

- United States enters the war

- Conflict has been going on for nearly three years

- Armistice comes into effect, leading to treaties and the war’s end

Bucknellians who served as …

soldiers, nurses, aid workers, ambulance drivers

- Dwite Schaffner, Class of 1916, earned the highest award a soldier can receive for acts of valor. 3 Distinguished Service Crosses

- Dwite Schaffner, Class of 1916

- Charles O’Brien, Class of 1909

- William Chalmers Acheson, Class of 1916

Photo: L’Agenda

Joseph Aleshouckas, Class of 1915

Joseph Aleshouckas, Class of 1915During the war: Second lieutenant in the 168th Aero Squadron of the Army Air Service

Special note: After the conflict ended, Aleshouckas’ squadron was chosen to go to Germany to study that nation’s superior aircraft.

Researched by Professor Adrian Mulligan

George Potts, Class of 1913

George Potts, Class of 1913During the war: Lieutenant in the 47th Infantry of the American Expeditionary Forces

Special note: Received the Silver Star Medal for valor. A monument to his division stands today near Saint-Thibault.

Researched by A.J. Paolella ’18

Charles O’Brien, Class of 1909

Charles O’Brien, Class of 1909During the war: Soldier in the 306th Infantry Regiment of the American Expeditionary Forces

Special note: Recipient of the Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart.

Researched by Amy Collins ’18

Thomas Agnew, Class of 1920

Thomas Agnew, Class of 1920During the war: Member of Ambulance Unit SSU 525, comprising mainly Bucknellians

Special note: Received the French Croix de Guerre, an award for bravery.

Researched by Julia Carita ’20

KATHERINE BAKER,

Bucknell Institute Class of 1892

See Page 35.

Robert Preiskel,

Class of 1915

See Page 32.

This solid granite monument features a bronze plaque that memorializes “all Bucknellians who lost their lives as a result of service in the Great War.” It was dedicated in September 1919 by the Class of 1919.

The arched gateway leading to the Christy Mathewson–Memorial Stadium, as well as two bronze plaques listing the names of the men and women of Bucknell who served in World War I, was dedicated in 1927.

A bust of Dwite Schaffner, Class of 1916, sculpted by Charles Parks, was unveiled in 1996 and now resides in the Kenneth Langone Athletics & Recreation Center (KLARC). Schaffner received the Congressional Medal of Honor for acts of valor during his service in World War I.