am Barlow, a tall, slim man with a long gray beard and close-cropped grizzled hair, sits in the small, tall-windowed interview room at the State Correctional Institution at Coal Township. He’s describing his reaction to news he’d longed to hear for a half- century.

“It’s the most surreal thing … In 1969, I was at SCI Camp Hill, sitting on death row, waiting for the governor to sign my death warrant. Fifty years later, I’m at SCI Camp Hill waiting for the governor to sign my release paper.”

The murder that Barlow did not commit but that landed him in prison for most of his life occurred two months after his 18th birthday.

On Dec. 2, 1968, Barlow drove from Pittsburgh to Harrisburg with two 17-year-olds who would eventually seal his fate. Sharon “Peachie” Wiggins and Foster Tarver shot and killed retired truck driver George Morelock as they robbed Dauphin Deposit Bank. Outside, waiting to drive the getaway car, Barlow heard gunshots but didn’t learn Morelock died until he was in Dauphin County Jail.

“My reaction was selfish,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘How did I get in here, and how do I get out of here?’ I said I didn’t do it.”

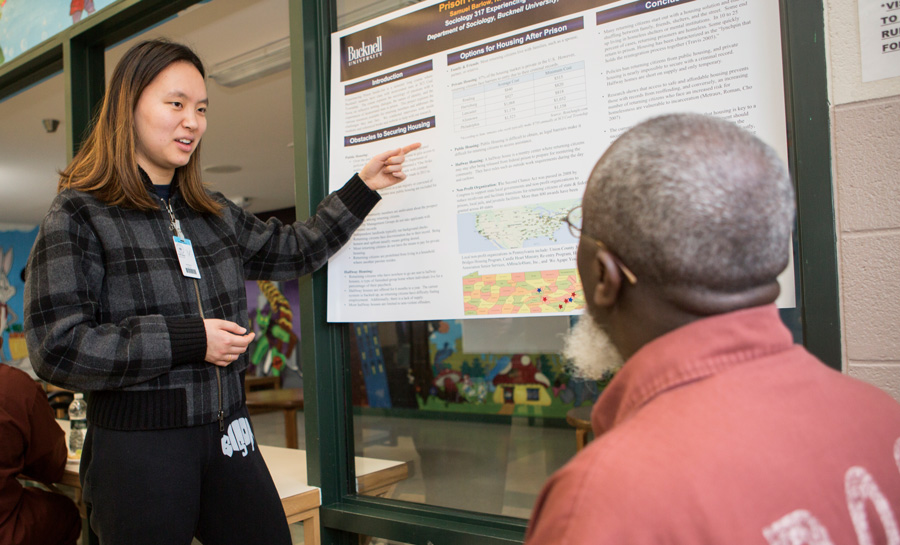

Bottom: Ella Ri ’19 (left) and Sam Barlow (right) worked together this fall on a class project at SCI Coal Township.

But a three-judge panel thought otherwise. “My lawyer said, ‘If you plead guilty, they won’t press for the death penalty.” He pauses a beat. “I was naïve.”

After spending several months on death row, Barlow won an appeal and was resentenced to life without parole. His shot at redemption began in 2016 when the U.S. Supreme Court banned mandatory life sentences for juveniles convicted of murder.

As a result, Dauphin County District Attorney Fran Chardo was reviewing old juvenile murder convictions and met with Tarver in advance of his release in June 2018. Recounts Chardo, “I said, ‘It bothers me a great deal that you’re the trigger man, and you are going to get out because you were a month and a half short of your 18th birthday, but Barlow isn’t. I don’t think that’s fair.’

“I began to do research on Barlow and found that he’d done very, very well in prison,” Chardo says. After interviewing Barlow and hearing him take responsibility — he was the only robber able to drive, so the murder wouldn’t have occurred without his assistance — Chardo decided to support him.

Two things sustained Barlow for 50 years: his Islamic faith and his desire to improve his mind, which led him to send “57 letters to universities in Pennsylvania asking them to start an Inside-Out class at Coal Township,” he says. Professor Carl Milofsky, sociology & anthropology, was the only person who responded, says Barlow.

Milofsky led his first Inside-Out class this fall at SCI Coal Township; Barlow and seven other inmates joined 14 Bucknell students in the prison classroom. Articulate, poised and dignified, Barlow soon became a favorite of students like Kelsey Birmingham ’19, who worked with Barlow on a class project.

“He’s a very intelligent person who still has a lot to offer,” she says. “He has great ideas.” One involves starting a recycling company where former inmates can work cleaning and sorting trash that can be converted to building materials or shipped to China, she says. Barlow hopes to work as a consultant for such a venture.

Since the class ended, Milofsky continues leading a Coal Township “think tank” on incarceration. One participant is Rich Stover ’20, whose honors thesis is based on interviews with inside students, including Barlow, who raise money to benefit coal-region communities.

“I want to know what changed them to become more charitable in their outlook,” Stover says. “This is just begging for an academic explanation.”

Stover’s support of Barlow goes beyond the classroom. He attended his March 14 commutation hearing in Harrisburg, where Milofsky and Chardo testified on Barlow’s behalf.

“I remember when all five [on the board of pardons] said yes to Sam’s release,” Stover says. “Sam’s fiancée [Karen Lee] was huddled over crying, and I was crying.”

On April 30, Gov. Tom Wolf signed the commutation warrant for Barlow, whose 50-plus years in prison are a record for a commuted person in Pennsylvania, according to spokesperson Christina Kauffman. Barlow was released May 13 to a Philadelphia halfway house, where he will live for the next year readjusting to a world he hasn’t known for 50 years. Unless Barlow reoffends, he is on parole for life. He expects Bucknell to play a key role in his future.

Milofsky is helping to arrange housing in nearby Milton, Pa., and exploring job options locally as well as in Philadelphia at an inmate rehabilitation program where Barlow’s former classmate Virginia Whelan ’19 works.

Says Thomas McGinley, superintendent of SCI Coal Township and another Barlow advocate, “Any offender who leaves our facility needs not only structure but also support. I think Sam will have that support system just through his Bucknell University contacts.”

Barlow agrees. “Bucknell stepped up in a big brother, big sister role, not just for me but for the whole community, which is what a University should be involved with — the community.”