egan. Cud chewer. Sports enthusiast. Ungulate. Nonblinker. These are just a few words that describe Bucknell’s beloved mascot, Bucky the Bison. However, they represent a mere fraction of Bucky’s rich and storied life. Bucky himself is a creature of few words (he declined to be interviewed for this piece) so it’s understandable that not everyone knows the extent of his family history. But we know that he is extremely proud of his heritage — one that is intertwined with the very history of our nation.

A long time ago, Bucky’s earliest ancestors lived somewhere in Asia. Then, between 95,000 and 135,000 years ago, his intrepid forefathers migrated across the Bering Land Bridge to North America. Scientists believe this because two of those plucky fellows left behind some mitochondrial DNA — one in a 120,000-year-old fossil discovered in Colorado, another in a 130,000-year-old fossil found in the Yukon.

Those early adventurers spread throughout the continent, until tens of millions of bison roamed North America. They were enthusiastic foodies feasting on grass and other plants for nine to 11 hours each day, and migrating to and fro with the seasons. Sometimes, magpies kept them company, perching on their backs and snacking on insects plucked from their coats. And, Bucky’s ancestors were a boon to the Plains Indians, providing food, clothing and shelter made of hides and fur, plus tools of sinew and horn.

Then, during the 18th and 19th centuries, came a difficult period for the bison: the westward expansion of white civilization, and with it, the wide-scale slaughtering of buffalo — for sport, subsistence, commercial sale of meat and hides, and as part of a late-1800s U.S. Army campaign to control Native American tribes by cutting them off from their most important resource. (The name of one 19th-century hunter in particular, William F. Cody, aka Buffalo Bill, always makes Bucky shudder.) Shockingly, by 1889 there were fewer than 1,000 bison left in all of North America.

Happily, around 1900, conservationists and cattlemen took action to protect Bucky’s ancestors. Today, there are roughly half a million bison on our continent; the purest remaining population lives in Yellowstone Park.

Now comes a touchy subject in Bucky’s family lore: Though Bucky is a proud Pennsylvanian, the experts are not quite sure if (wild) bison ever lived in the Keystone State. The issue seems to be that no scientist has ever found bison bones in the area. There are mentions of local bison in early writings and Pennsylvania folklore, but there’s also reason to believe these are incorrect.

Whether or not wild bison ever lived here, what we do know is that in 1923, Bucknell chose the bison as its school mascot. It’s a pairing that seems meant to be, but in fact, Bucky had some competition for the job. It used to be that Bucknell’s various sports teams used multiple names: Bucknell could have become the home of the wildcats, timber wolves or another contender. However, William Bartol, Class of 1872, a former athlete and head of the math department for 46 years, began pushing for the teams to have one consistent name. He suggested the Bison around 1910 (though it took a while to become official) because of Bucknell’s proximity to areas believed (perhaps erroneously, we now know) to have been populated by the American bison in the late 1700s.

Then came 1946, when John Shumberger P’48 of Allentown, Pa., donated a real, live bison to campus, named … Bucky. His handler, William “Bill” Watkinson Jr. ’49, recounted their adventures in the Fall 2018 issue of Bucknell Magazine. Bucky debuted at the 1946 Centennial Homecoming football game. “At halftime, I would hold one end of the leash behind my back and run around the field with the bison chasing me, about 10 feet behind. The crowd in the stadium roared,” Watkinson wrote.

Sadly, the first Bucky was never healthy and died after one season. But happily, the Bucky we know and love arrived soon after, in 1949.

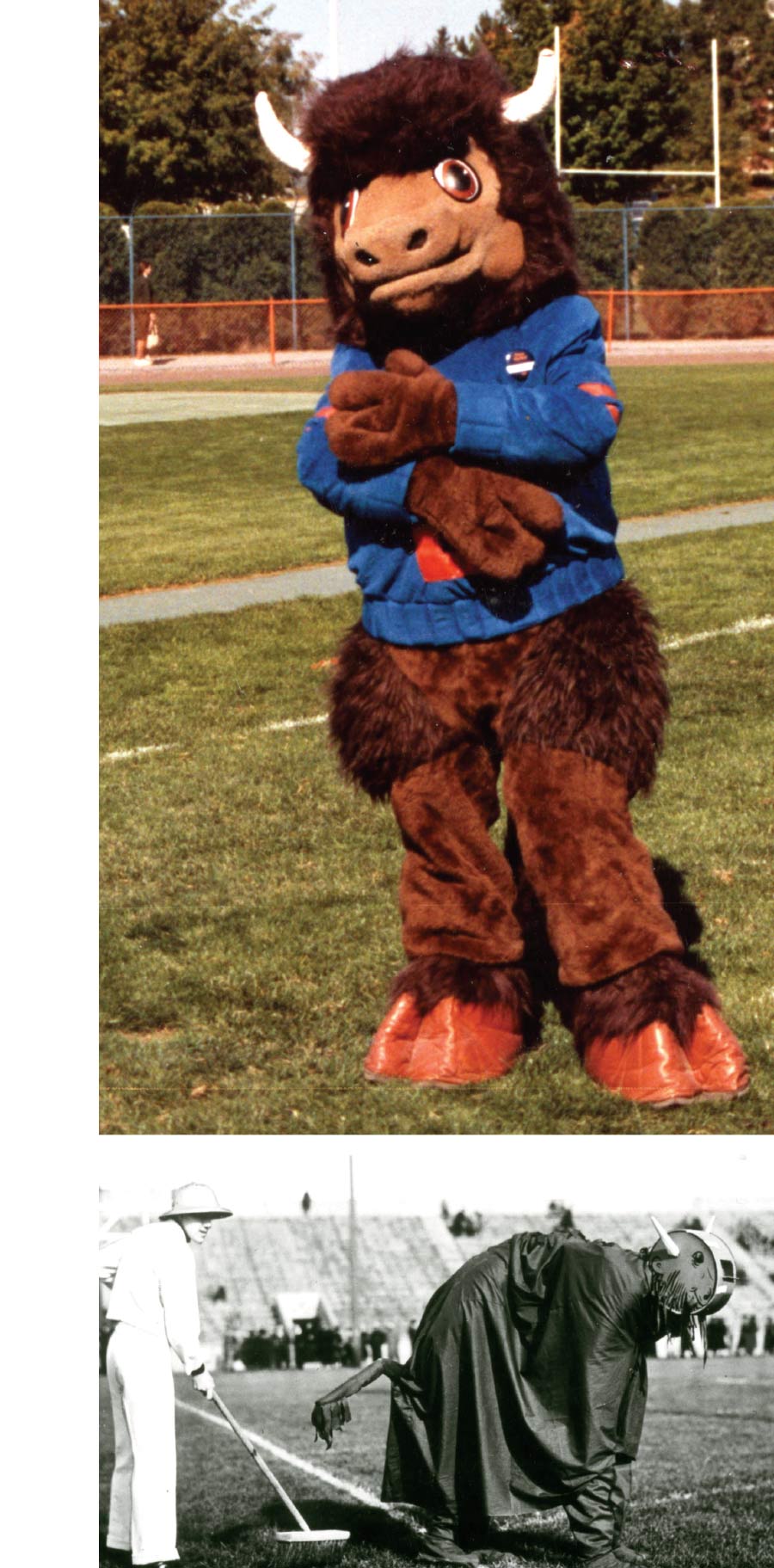

We hope Bucky will forgive us for mentioning this, but pernicious rumors have long circulated that Bucky is actually a Bucknell student — often a member of the cheerleading squad — wearing a bison costume. The rumors hold that in November 1949, the Bison Club purchased the first Bucky costume, as seen in a 1951–52 L’Agenda photo. It’s unclear where the rumors come from, but perhaps they are inspired by Bucky’s incredible ability to walk on two legs — extremely rare among his kind. Miraculously, a few decades later, a second bison also developed this ability: Becky the Bison, who joined Bucky in 1990, before retiring in the early 2000s.

Out of respect to Bucky, we won’t dwell too much on the rumors. Suffice it to say that through the decades, Bucky has led an adventurous life, both on and off the field. During the ’80s, he was kidnapped by University of Pennsylvania hooligans, as mentioned in a January 1990 Bucknell World, and required $2,500 in medical care that altered his appearance. (The conspiracy theorists say the “treatment” was really the purchase of a new suit, with reinforced horns and a stockier body.)

After the incident, then-cheerleading coach Beth Engleman began the practice of having a student act as Bucky’s bodyguard. Bucky broke his silence in 1990 to explain to Bucknell World, “I can’t talk to people and tell them to leave me alone, and I’m not allowed to hit people.” (The rumor mongers also say that during that time, Bucky was actually a she, a sophomore from the cheerleading squad.)

Bucky today is such an integral part of the campus that it feels uncanny to imagine a time when he wasn’t among us spreading school spirit throughout the student body. A devoted humanitarian, Bucky has visited children in hospitals, attended innumerable charity and fundraising events and cheered generations of student athletes to victory on the field and court. Bucky knows he is loved, but it’s worth saying again: Thank you, for everything you’ve done. Go Bison!

Right (top to bottom): Bucky in 1985. The Bison mascot with his cleanup crew at the 1936 Homecoming game against Lafayette.