The current craft-beer renaissance is the most recent step in a long recovery from the effects of Prohibition, which left only 331 breweries on its repeal in 1933, compared to 669 when it was enacted in 1920. In the 1940s and ’50s, most surviving breweries followed the market trend that called for beer with an American identity. This led to the dominance of one style of beer — the yellow, fizzy liquid now referred to as American adjunct lager, typified by Budweiser and Miller — and a market consolidation that dropped the number of breweries below 100 in the late 1970s.

The 1978 repeal of restrictions on homebrewing allowed beer drinkers to concoct libations to suit their own tastes and led to the proliferation of styles other than American lager, such as pale ales, stouts and, of course, hoppy India Pale Ales (IPAs). These homebrewers included pioneers of craft-beer evolution: Fritz Maytag of Anchor Brewing Co., Jim Koch of Sam Adams-producer Boston Beer Co. and Paul Shipman ’75, co-founder of Seattle- based Red Hook Brewing Co. They helped lead the growth of microbrews beginning in the 1980s, until a shakeout in the 1990s toppled breweries that focused on finance rather than quality beer and made room for the rise of craft beer — and small, independent operations that extolled drinking local. New breweries such as Victory Brewing Co., Russian River Brewing and Dogfish Head Brewery embraced the movement and championed the revision of antiquated alcohol laws to allow for small brewery licenses, which resulted in a significant increase in breweries — from 284 in 1990 to a staggering 6,372 in 2017, according to the Brewers Association.

The alumni brewers featured in the following pages agree that brewing a great beer requires two fundamental elements: consistency and creativity. In other words, you need scientific, process-oriented skills and some degree of creative, artistic talent. This is why a liberal arts education from Bucknell, no matter the major or concentration, can be the perfect recipe for students who join this growing industry.

Jennifer Yuengling ’93, vice president of operations for the Pottsville, Pa.-based D.G. Yuengling & Son Inc., is a sixth-generation brewer and part of the vanguard of women advancing in a male-dominated career. The company is now led by the four Yuengling sisters.

“It’s satisfying to see women immerse themselves into the brewing culture and make contributions, even if just to break down stereotypes and provide diversity,” Yuengling says.

She’s benefited from the growth of the beer industry as well as close relationships with fellow brewers. “Between the 20 years that I’ve been involved, and learning from my past five generations, I’ve learned the adversities that face the brewing industry are real,” she says. “That’s why we support each other.” But to be successful, Yuengling warns, brewers must regularly educate themselves.

From the start, Yuengling sought expert training, earning a brewing certificate from the Siebel Institute of Technology. “It was intense and rigorous,” she says. “It was science oriented and gave me an appreciation for how our brewers formulate beer. Without brewing education, it is extremely difficult to make a consistent and quality product, and the consumers ultimately determine whether your beer can withstand the test of time.”

As a brewer she’s often asked, “Is beer better than wine?” Says Yuengling, “I’m biased of course, but beer has a broader flavor spectrum compared to wine. Beer can be sweet, sour, salty, bitter. Especially in food pairings beer is amazing because it can be compared and contrasted with different foods, so it can appeal to anybody.”

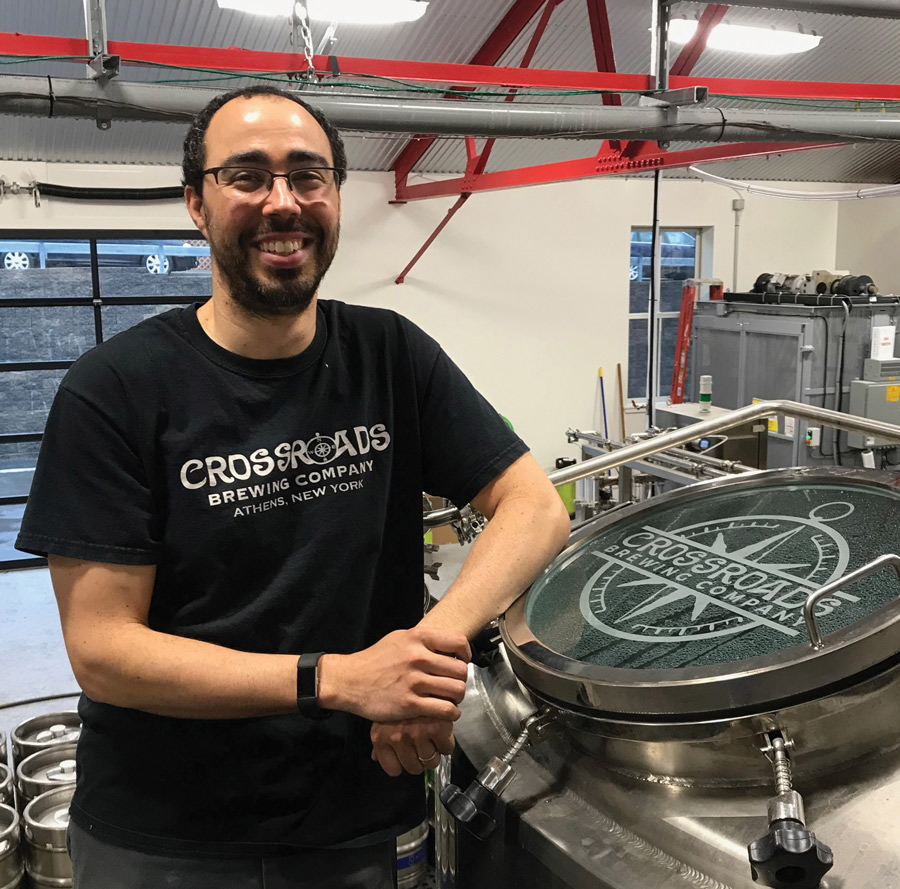

head brewer at Crossroads Brewing Co.

As the co-founder and former CEO of Seattle’s Redhook Ale, Paul Shipman ’75 helped to change the way Americans drink beer, just as Starbucks has changed the way Americans consume coffee.

But before Redhook, there was Bucknell, where Shipman stood out with his wild, jet-black hair, black beard and barking laugh. He’d describe an idea for a film, punctuate a story or drive home the point in an argument while waving a Lucky Strike. The English major was very persuasive, a trait that would serve him well as a progenitor of the craft-beer movement.

Shipman’s first acquaintance with a beer that was very different from the pilsner in America occurred in London during his junior year. Shipman had convinced the English department to allow him to study abroad, first in Paris, where he studied wine before encountering English ale houses.

Back in Lewisburg his senior year, Shipman took a part-time job promoting products for a wine and liquor manufacturer, a gig that allowed him to practice his sales and marketing skills, targeting fraternity and sorority leaders.

After Bucknell, Shipman earned an MBA at the University of Virginia, magna cum laude.

Work with a winery took Shipman to Seattle. While developing a new marketing concept, he connected with Gordon Bowker, a founder of Starbucks. In 1981, they began brewing Redhook, a locally crafted ale. There was almost nothing like it on the market — most bars served Budweiser and Miller on tap, as well as an occasional local brand. IPA’s, Porters or Stouts were nearly nonexistent.

When Shipman announced Redhook would go public in 1995, the national media took notice. Wall Street went for it as well and soon the company was trading as HOOK. Redhook became a national brand, with Bavarian-style breweries in Seattle and New Hampshire that included entertainment and dining. Shipman’s creative talents, honed while a student at Bucknell, hit the mark and changed the way Americans think about and drink beer.

Shipman remained as CEO until his 2008 retirement. Since then, he says, “I have been in awe of the rising quality of the beers and the growing passion of the consumers.” Still living in Seattle, he enjoys time with his wife, Patti, two children and three grandchildren, as well as traveling. — John Collier ’75

Bucknell’s influence on the craft-beer business is not limited to the United States. Chris Hainge ’02, co-owner and brewer at Kyoto Brewing Co. in Kyoto, Japan, was a double major in East Asian studies and religion at Bucknell. Hainge was introduced to homebrewing by a friend during his junior year, and “it opened the floodgates and changed my perspective,” he says. He moved to Japan in 2003, and his passion for brewing grew.

In 2012, Hainge took an online brewers course that concluded with an internship at California’s Lost Abbey/Port Brewing Co. He worked at several breweries in Japan until he and his partners were ready to launch Kyoto Brewing in April 2015.

One image of the brewing industry that Hainge dispels is that it’s “quite glamorous. People think that you just throw hops into kettles all day long, when 98 percent of the time I’m just cleaning something. If you want to brew for a living, make sure you have the dedication and passion for it.”

But passion can have its payoffs. According to Hainge, it is a fantastic time for brewers in Japan. “People are looking for styles other than traditional German lager. We’re having a renaissance of craft beer, similar to the U.S. about 10 years ago,” he says.

Using a house strain of Belgian yeast, Kyoto Brewing has set itself apart by brewing Belgian-influenced beer yearround; beer review website ratebeer.com named Kyoto Brewing the top brewer in Japan for 2017. Unfortunately, Kyoto beer isn’t available in the U.S.; you’ll have to go to Kyoto to experience it.

Hainge offers the following advice to Bucknell students contemplating beer industry careers: “You never know where life is going to take you. If I had never taken East Asian studies or hadn’t decided to watch my friend homebrew, I wouldn’t have the life I have now. You never know where a certain choice is going to take you, so don’t be afraid to try things.” — Matt Brasch ’96

As a neuroscience major, Alexandre Apfel ’12 never considered a brewing career. But while interning in a cognitive psychology lab after graduation, he also washed dishes at a brewery and was introduced to brewing science. Now a brewer at Fiddlehead Brewing in Shelburne, Vt., Apfel finds his training in the scientific method helps him “identify and manipulate the variables behind brewing to influence the results intentionally,” he says. He also embraces brewing’s creative aspects. “One of the most exciting things you can do is take inspiration from a poem, painting or pattern in a rug and write that into a beer recipe,” he says. — Matt Brasch ’96