In A League of Their Own

photograph by Emily Paine

In A League of Their Own

photograph by Emily Paine

The Ironwoman

Ava Warfel ’22

Warfel’s meteoric success is stunning but perhaps not surprising to former classmates. After all, she graduated from Bucknell in just three years — balancing a demanding student-athlete life as a biology major and cross-country runner while working full time as a night-shift paramedic in Lewisburg.

That’s why Warfel’s alarm beeps at 2 a.m. on weekdays. Before she heads to Alvernia University’s health center where she works as a nurse, she does a double or triple workout (an hour swim followed by a 90-minute ride followed by a 40-minute run, for instance).

This year, Warfel will transition to elite status. Becoming a professional triathlete isn’t lucrative. It won’t allow her to quit her job. But sponsorships help cover race entry, travel and gear.

“My coach says that I like to suffer,” she says. “I think that I like to suffer with purpose. I like when it hurts, and when you think you can’t do something, but then you push through it. The more I put into this sport, the more I get out of it. That’s the essence of it for me.”

How to Stay Calm Under Pressure

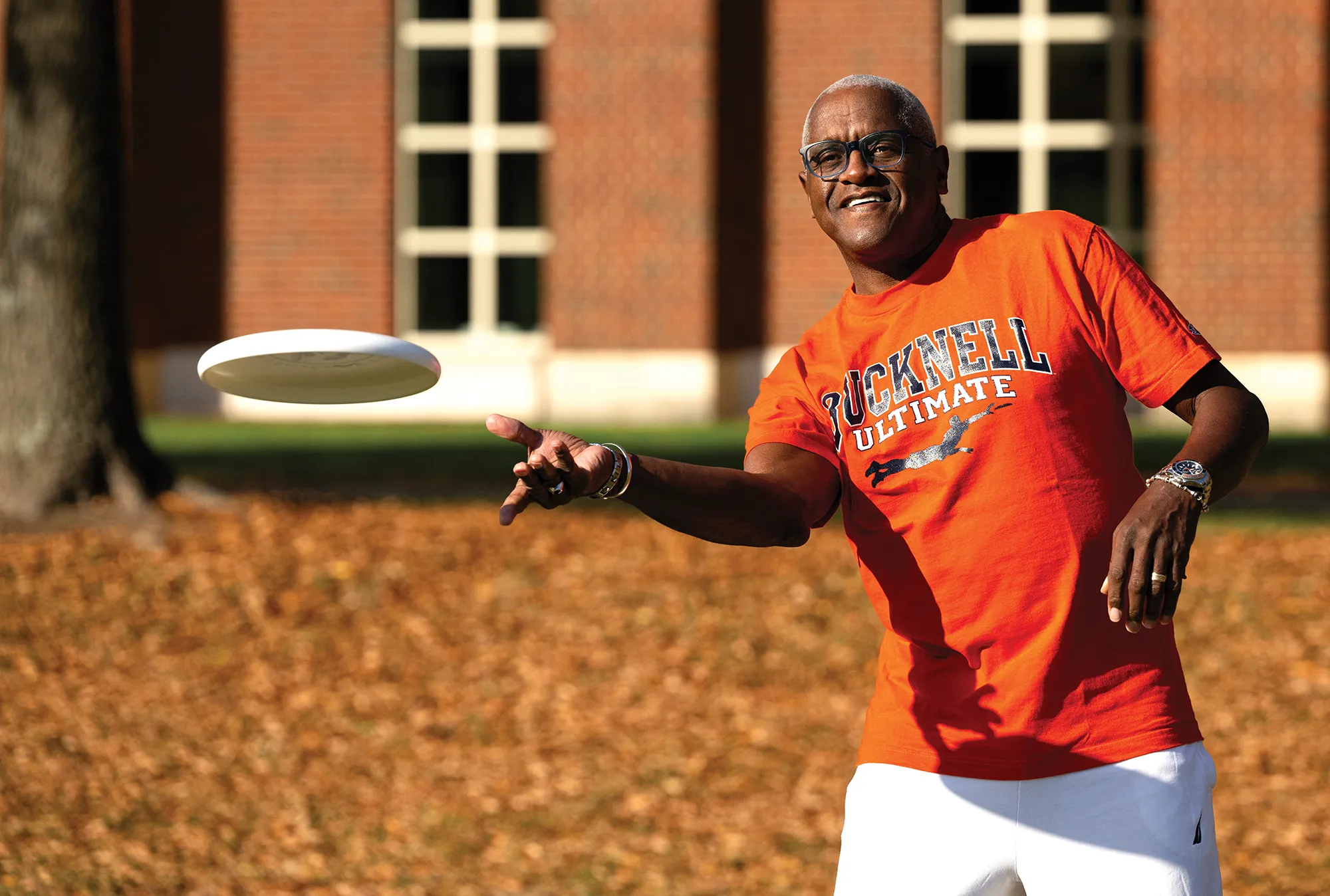

The Disc-throwing Icon

Harvey Edwards ’78

Although he was recruited to play for the Bison, Edwards wasn’t getting much court time. So for fun, he started organizing games of Ultimate Frisbee on campus. Before long, he had a team of athletes from a mish-mash of sports who, like Edwards, were craving a change of pace. He ended up quitting basketball and founded the Bucknell Mudsharks (named for a Frank Zappa song).

After graduating with an English degree, Edwards took a job as a preschool teacher and spent his weekends advancing his Ultimate Frisbee career. Over the next three decades, Edwards accumulated accolades and credentials, including three world championship titles. In recognition of his accomplishments, Edwards was inducted into the Ultimate Frisbee Hall of Fame in 2007.

Today, Edwards is enjoying his newfound retirement from a 44-year education career (after 29 years of teaching English at Selinsgrove Area High School, he joined the English faculty at Susquehanna University) — and a new pair of knees. Decades of athletic wear and tear caught up with him, he says, requiring double knee replacement surgery in October. Yet he remains active with the sport, working to introduce new generations to the game. “I think there is no sport more American than Ultimate Frisbee,” he says. “It’s inclusive, it’s accessible and it’s all about the spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play.”

How to Improve Your Throw

The Paddling Powerhouse

Nathan Humberston ’08

That prestigious international, multi-sport competition was an important stepping stone to an even more prestigious international, multi-sport competition: the 2024 Olympic Summer Games in Paris.

In March, as this issue was going to press, Humberston was competing in the U.S. National Team Trials and vying for a spot on Team USA. Competing in Paris would be kismet for Humberston, who majored in French at Bucknell and taught French after graduation. It’s also the 100th anniversary of his sport’s Olympic debut; canoe sprint, which kayaking is part of, was introduced at the 1924 Games in Paris.

Humberston’s optimism isn’t foolhardy. It’s rooted in a relentless work ethic, a fierce competitive drive and genuine love for his sport.

He dove into water sports at age 8 when he joined his hometown swim team. Swimming was his athletic focus for the next decade, including during his first year at Bucknell. But the rowing team made a convincing argument for him to transition to crew. He already had endurance, speed and power. Over the next three years, he developed technical skills while learning how to navigate water and weather conditions on the Susquehanna.

After graduation, he continued to seek athletic challenges. In 2014, his New Jersey ocean lifeguard squad won the U.S. Lifesaving Association’s National Lifeguard Championships. In 2018, he paddled 40 miles nonstop around Bermuda to see how fast he could do it (just under six hours). It was around that time when a seasoned world-class kayaker took notice and offered to coach him.

Now, Humberston is all-in on his Olympic dream. In 2021, he moved to San Diego where he can kayak year-round and work a fully remote job for a tech startup that affords him flexibility to train. “I enjoy challenges and figuring out how to deal with them,” he says. “I’m always looking forward, always trying to improve. I haven’t hit my limit in this sport yet, so I’m going to keep pushing. It’s fun to chase a big goal and see what you can get out of yourself.”

How to Paddle With Power

The Pickleball Master

Kent Lindeman ’92

Lindeman progressed from novice skeptic to national champion in just three years. “When a friend introduced me to the game in 2017, I initially dismissed it. I thought pickleball was a hobby better suited for people at a retirement community,” says Lindeman, who majored in political science at Bucknell and owns HollandParlette, an association management company. “But I started playing and discovered it’s truly addictive.”

Lindeman isn’t alone in that discovery, of course. Pickleball, a cross between table tennis, badminton and tennis, is one of America’s fastest-growing sports with a growth rate of more than 158% over the past three years, according to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association.

While his tennis background equipped him with some carryover skills, Lindeman says pickleball is an entirely distinct sport that required a rewiring of his instincts and mechanics. “It’s a finesse game,” he says. “High-level pickleball players execute delicate dinks and well-calculated, angled shots. It’s a different approach than hitting a tennis ball with power and topspin.”

As the executive director of the Association for Applied Sport Psychology, Lindeman espouses the physical and mental health benefits of his sport at national conferences. “Developing new skill sets and friendships, especially as we get older, is just so positive. It helps your overall well-being, mental health and quality of life,” he says. “Pickleball has that kind of impact.”