Jennifer Rich ’16, an OB-GYN resident, gives the same response. So does Connor McLaughlin ’16, a resident in internal medicine.

For David Rubin ’13, an anethesiology resident, the word is “OK.” He’s coming off a 24-hour shift and three hours of sleep.

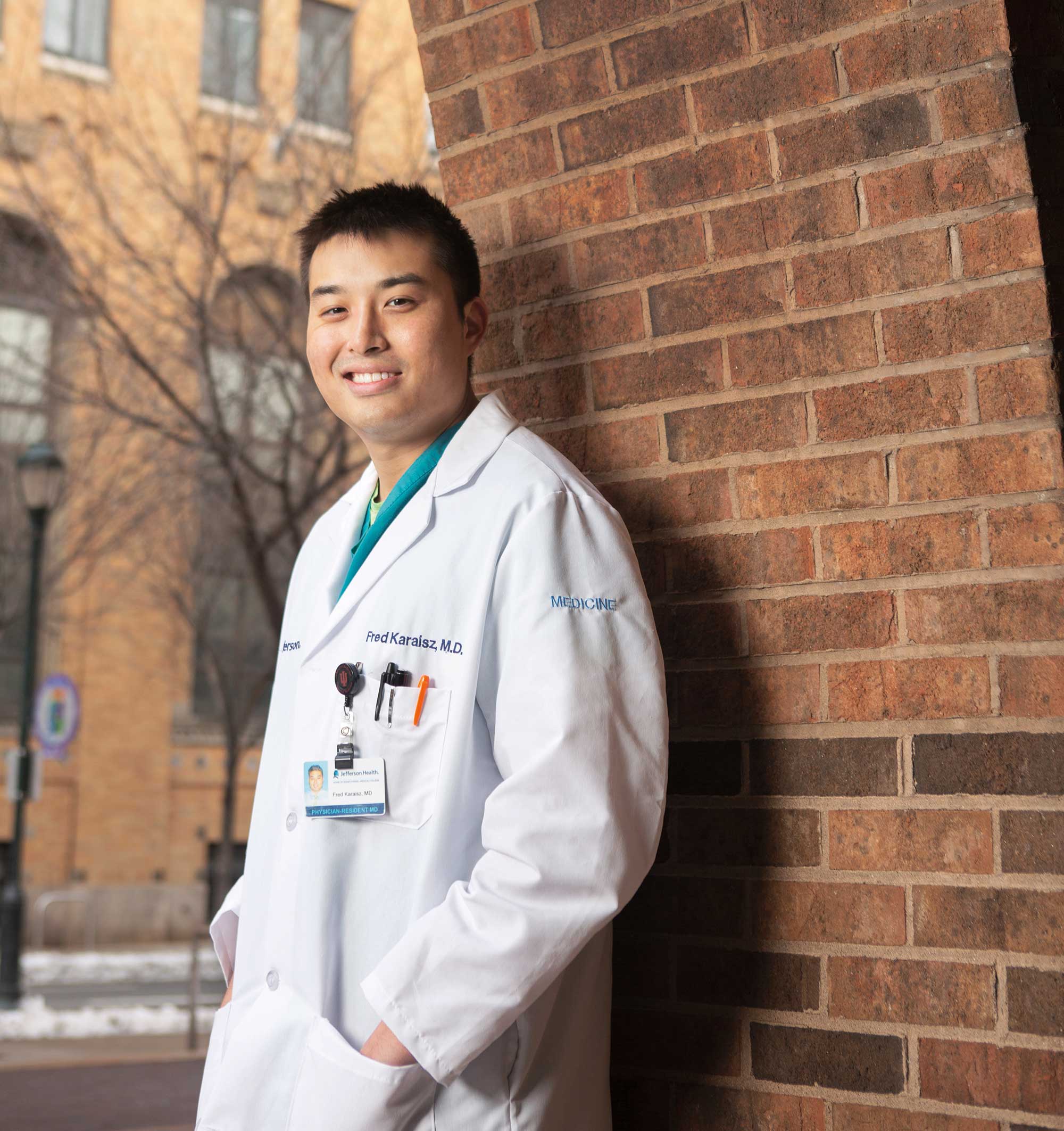

Internal medicine resident Fred Karaisz ’14 says his word is “hungry.” It’s 6 p.m., and having just awakened after his latest shift, he’s starting to gobble a quick microwave dinner. With his scrambled schedule, he averages only five hours of sleep a night.

This stage of a doctor’s professional training — serving residencies at a hospital and rotating through different specialties — is notorious for the rigorous demands, both physical and mental, it imposes. Some shifts last all day and night, and constantly changing schedules force residents to grab a few hours of sleep whenever they can. The pandemic amplifies all those normal stressors, bringing regular exposure to patients carrying a virus that kills with alarming frequency.

Karaisz casually mentions that he came down with the virus earlier that autumn. “A lot of us have had it,” he says. Fortunately, it was a relatively mild case. “It felt like the flu,” he says. “I didn’t have a high-grade fever, but I was very fatigued. I lost my sense of smell. I had a rash.”

It laid him low for a week and a half, then he went through the recommended quarantine before returning to work. “Like most who are young and healthy, it really wasn’t that bad for me, but what’s scary about the virus is that it’s very unpredictable,” he says. Karaisz cautions that asymptomatic people can carry the virus and spread it to people who face much higher risk.

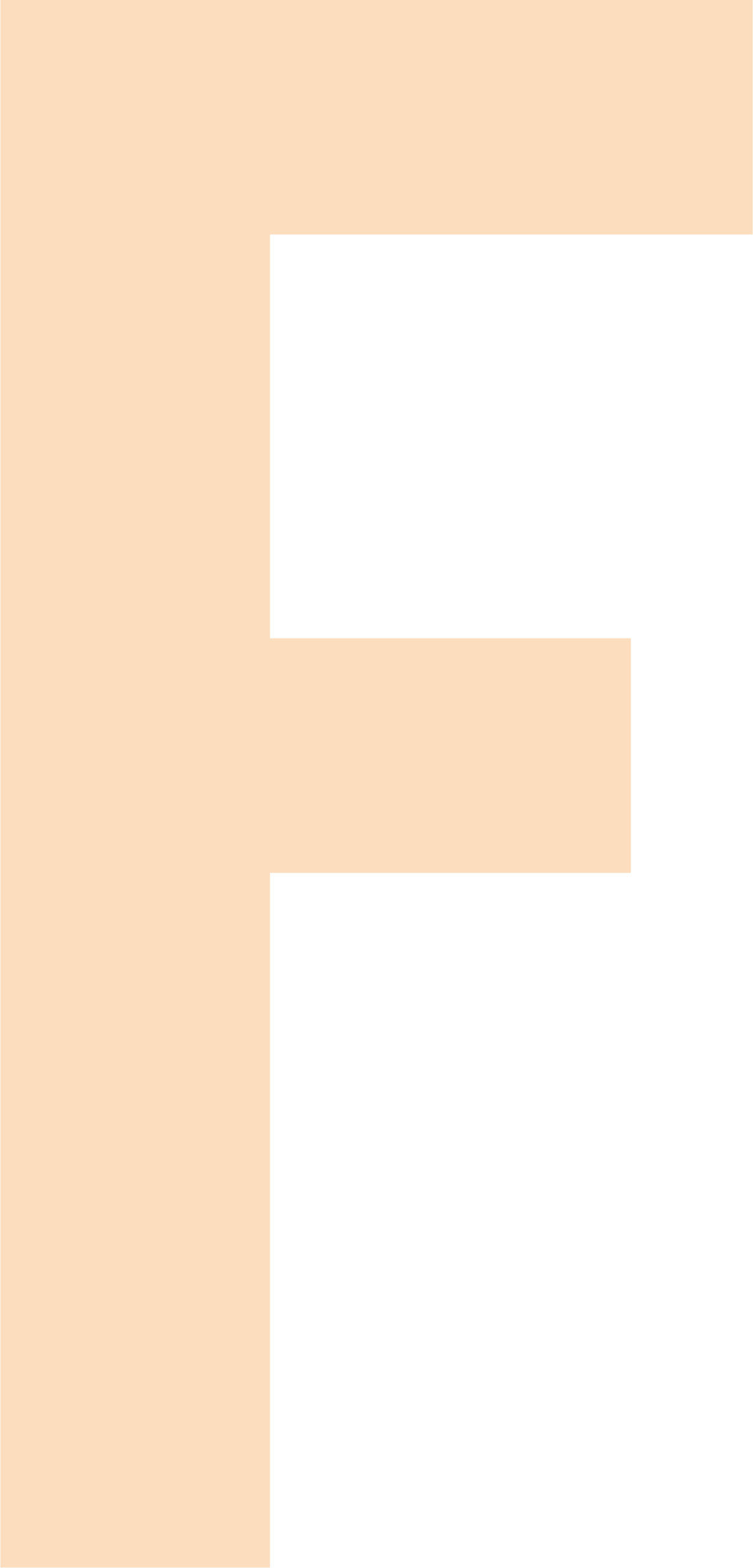

Rich, the OB-GYN resident, has been tending to pregnant women who are ready to deliver. She’s encountered some resistance to the visitation restrictions required by the pandemic: Only one helper is allowed to accompany the mom-to-be, and the mom needs to have a COVID test.

“The vast majority of patients are understanding and willing to do what is safe for themselves and our staff. It just puts us in a hard spot if the patient refuses COVID testing,” Rich says. While you want to be as supportive as possible during what should be a joyful time, “it puts us at risk if people come in who may be positive for COVID or aren’t wearing masks.”

“Everybody’s seen it all when it comes to mask etiquette,” McLaughlin says. He points out that nurses have even more reason to be upset. “They have the most patient contact. They’re doing the COVID nasal swabs.” Seecof explains, “The sheer number of people dying should alert the population at large — this is a big deal.”

The tools in the residents’ arsenal, especially with severe cases, are limited. McLaughlin mentions that when patients go on ventilators, “the odds are still very much against them, even though you’re doing the only thing you can do at that point.” Interviewed after the Zoom session, emergency medicine resident Emily Bollinger ’16 says treating COVID patients “has been a trying experience. You see the worst of it. We don’t have good therapies. It’s so heartbreaking. There’s so much more we have to learn.”

With patients’ families barred from routine hospital visits, doctors strive to keep them informed about their loved ones, but the demands of seeing other patients mean there’s not a lot of time for updates. “Finding that balance has been tough,” Rubin says.

Philadelphia has not, at the time of this writing, seen a tidal wave of COVID cases and deaths like those that overwhelmed hospital staffs in places such as El Paso in November and Los Angeles in January, leaving many medical personnel feeling emotionally devastated. But seeing patients struggling to hold onto life, for any reason, has an impact.

Working in certain areas of medicine, especially during this pandemic, sometimes leads doctors to create a protective psychological shell. “COVID or not COVID, we see a lot of hard things,” Lally says. It can be a struggle for the residents to conceal their personal feelings from patients. But whether they’re shown or acknowledged, those feelings are still there. “We bring a lot of it home,” says Karaisz. “It sits somewhere inside of us, and we don’t really acknowledge it. Some days it just all comes out.”

Bollinger and Seecof both say they’ve had to sharpen their skills in talking to patients and families that are confronting end-of-life decisions, such as signing a Do Not Resuscitate order, refusing a ventilator or pursuing comfort care that will ease death instead of continuing all-out treatment. Medical school education touches on this area, Bollinger says, but it doesn’t really train young doctors how to have those conversations.

When Rubin ran into Karaisz in the hallway, he realized they’d been in the same Biology 207 class. Seecof knew Jennifer Rich and her sister, Kim Rich Mosquera ’14, at Bucknell. Lally’s best friend and former roommate at Bucknell, Melissa Malkin Rubin ’13, is Rubin’s wife. Bollinger attended medical school at Jefferson with Rich and later worked with her during a rotation in labor and delivery. Seecof recognized Bollinger as a fellow Bucknellian when their separate work paths brought them together in the emergency room. “It’s funny when you’re on the other end of a call to the ER and you recognize the voice” as that of a Bucknell grad, McLaughlin says.

Jefferson has drawn such a significant cohort from Bucknell because some attended its medical school or another school in the Philadelphia metro area. Others have family roots in the region.

“I’m so happy to see people at Jefferson who are from Bucknell,” says Lally. “I get a pep in my step all day. It makes me feel more at home.” For Seecof, who hasn’t seen her family in a long time because they live across the country, there’s a sense of camaraderie that helps ease the strain of separation. “All the residents in the hospital have really come together,” she says. “Thomas Jefferson as an institution feels a lot like Bucknell — it’s a big place, but it feels very small,” thanks in part to her Bucknell colleagues.

So does this Bison “band of brothers and sisters” at Jefferson have a catchy name? Maybe a secret handshake?

No — or at least not yet. A minute or two of brainstorming among the tired Zoomers produced only two nominees, “JeffNell” and “BuckJeff.” Neither drew much enthusiasm. Maybe with time, possibilities such as “JeffNell Crew” or the “BuckJeff Bunch” will catch on.

As the November Zoom session wrapped up, Rubin offered this advice for fellow Bucknellians as the pandemic dragged into a second year: “Stay positive. Treat yourself to some ice cream at the Freez. And wear your mask.”

By early January, two highly effective coronavirus vaccines were being rolled out in the United States. Front-line doctors and nurses, including those at Jefferson, were among the first to get the shots. We circled back to the Bucknell residents.

“There is a palpable sense of excitement in the hospital surrounding the vaccine,” Rubin says. “We still have a ways to go [in controlling the pandemic], but the vaccine is an important step toward normalcy.” McLaughlin agrees that the vaccine is a game changer — but not an immediate game changer. “It will take many months to put enough shots in arms to reach a point where we have some semblance of herd immunity,” he says. Meanwhile, he’s worried that a false sense of relief will set in and lead to backsliding on mask wearing and social distancing.

Dispelling some of the public reluctance to accept the vaccine, Rich says, “This vaccine has been well-tested and is safe. This virus does not discriminate, and I’ve seen people of all ages and backgrounds become seriously ill from it.” She notes that some survivors are left struggling with long-term complications. “I encourage everyone to get vaccinated as soon as you are able.”

Summing up his time in residency during a global health crisis, McLaughlin says, “There are a lot of sad moments, but there are also a lot of moments of personal growth. Working in the first year of the pandemic “has been scary and challenging, but there are always moments of great reward and feeling you’re making a difference,” whether it’s with COVID patients or others. “I’m grateful to be equipped with the newfound resilience that the pandemic has required of so many of us in health care over this past year.”