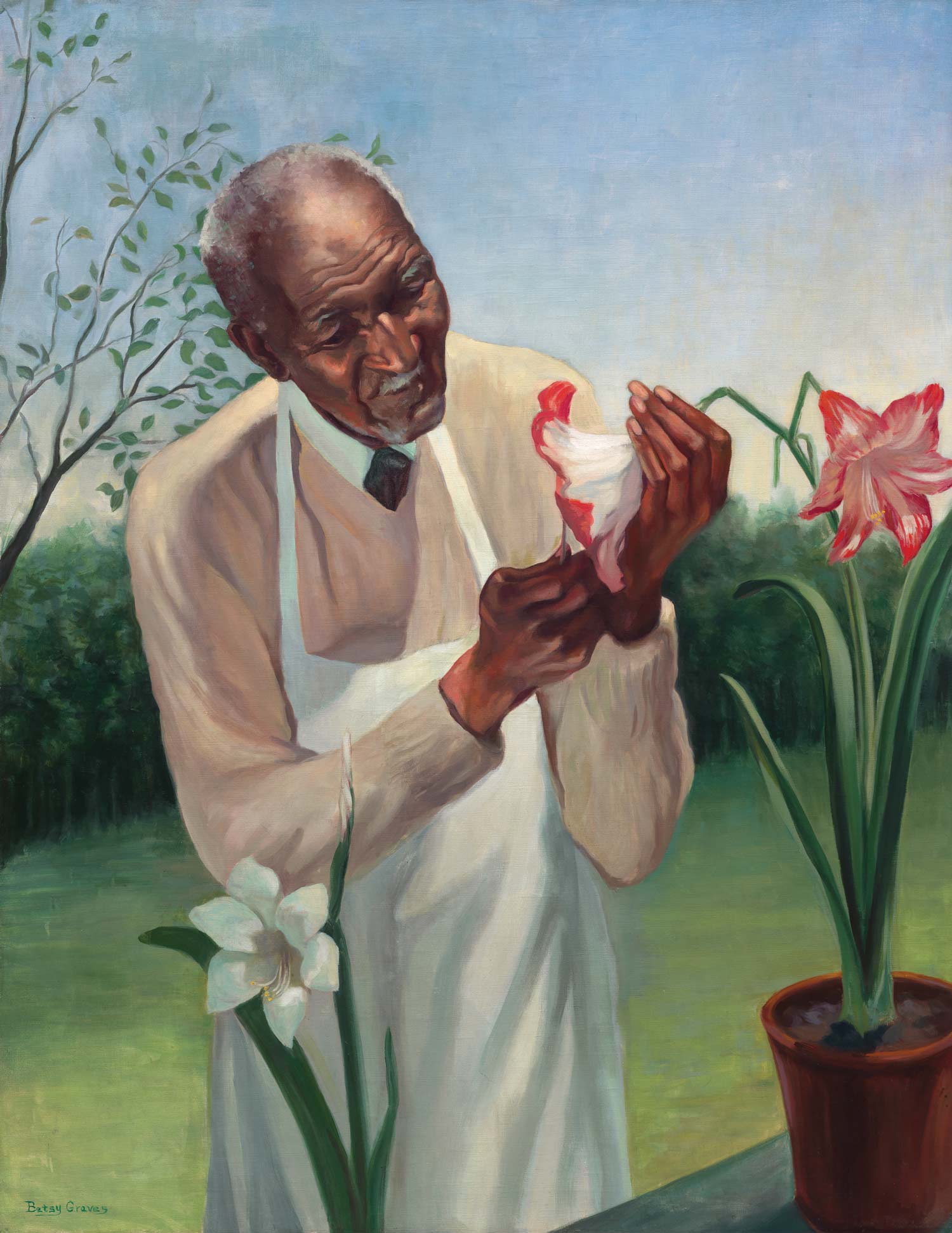

Betsy Graves Reyneau, 1942

Oil on canvas

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

© Peter Edward Fayard

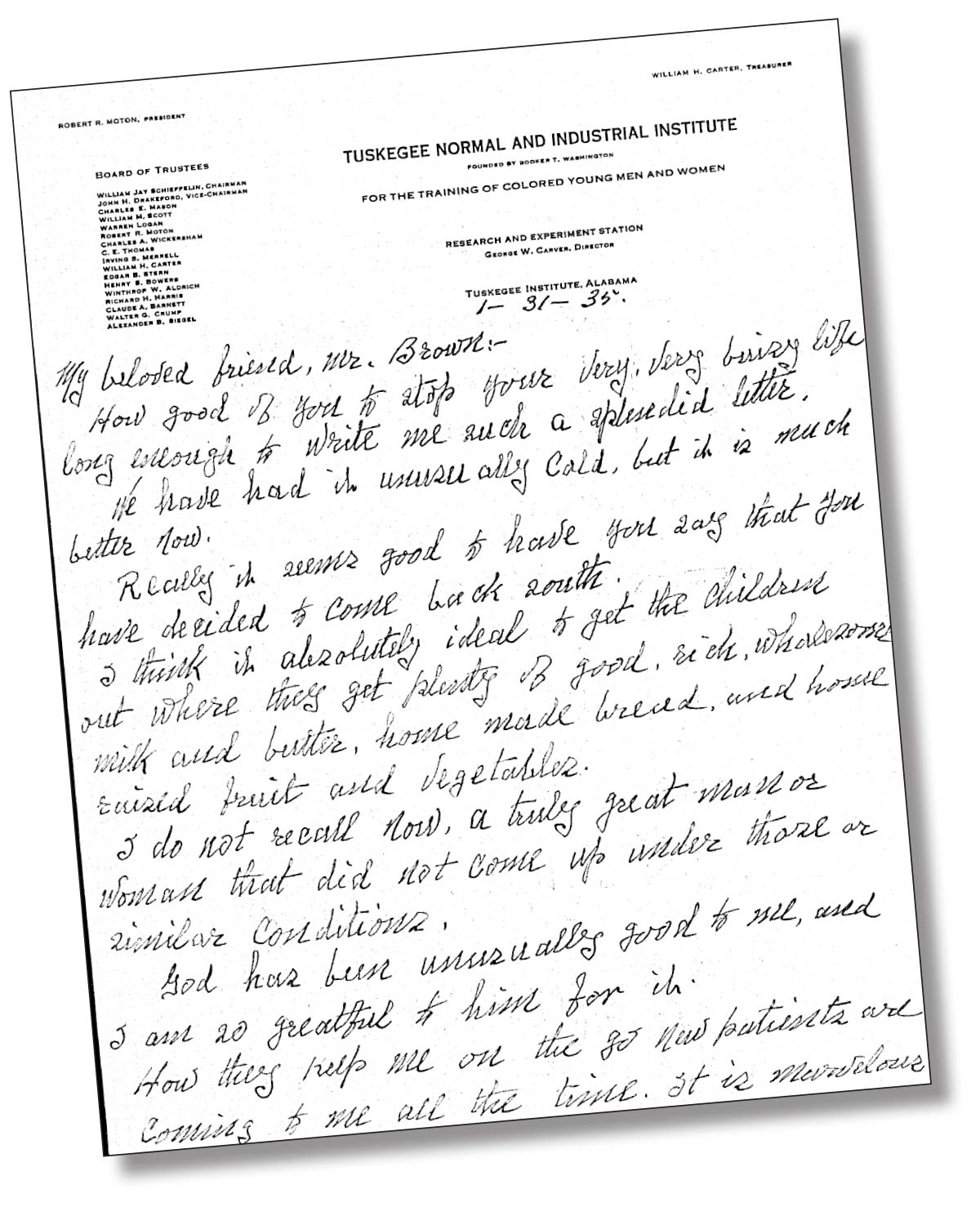

Betsy Graves Reyneau, 1942

Oil on canvas

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

© Peter Edward Fayard

niversity archives are spots of wonder filled with artifacts that are mesmerizing, quirky, priceless and surprising. At Bucknell’s Special Collections/University Archives, one of the surprising collections consists of letters to and from George Washington Carver. Born into slavery at the tail end of the Civil War, he became not only the first African American to earn a bachelor of science degree but also a prominent scientist who developed more than 300 household products from the humble peanut.

Generations of Bucknellians revered Carver’s correspondent, Forrest Brown, who arrived in 1930 as secretary of the Bucknell YMCA, recast as the Bucknell Christian Association in 1934. From that year until his retirement in 1966, Brown served as the association’s general secretary but also directed many of Bucknell’s intercultural and community service programs. The University’s Forrest D. Brown Conference Center at Cowan, which he developed, is named for him.

Welcoming and supporting students of color and international students was part of Brown’s life mission, according to his daughter, Carolyn Brown Chaapel ’56. International students “felt comfortable with him — coming into a new environment, a new land,” she recalls. “He wanted to give students coming here a sense of our people and our country.”

Their Lewisburg house was bustling with youthful energy. “Our home was an open door,” says Chaapel. “Dad had so many people of color and nationalities from all over the world come to our house.”

After her father died in 1980, Chaapel held on to one especially important collection of letters, which chronicles Brown’s friendship with Carver. In 2009, she donated the 80 letters the men exchanged between 1927 and 1942, the last dated six months before Carver’s death at age 78.

During their period of correspondence, Carver led the agriculture department at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama but also traveled, mainly in the South, to speak about and exhibit the products he developed, which included Worcestershire sauce, punches, cooking and salad oils, paper, cosmetics, soaps and wood stains, all derived from peanuts.

According to Chaapel, Brown met Carver when he worked for the YMCA, which arranged Carver’s speaking tours at colleges, universities and other venues. The situation was much like the one depicted in the Academy Award-winning movie Green Book, in which a white man drove and offered protection to a black musician on tour in the segregated South.

Brown either served as Carver’s driver or arranged for others to take the wheel. If Carver traveled alone by train, Brown would meet him or arrange for someone else to do so. “He had to be accompanied by somebody,” says Chaapel.

As depicted in Green Book, accommodations for blacks in the Jim Crow era were limited. “One time, Dad was traveling with him, and it was hard to find a place for him to eat, so Dad went in a restaurant and went into the kitchen and explained that he would like to get some food for Dr. Carver,” Chaapel relates. The cook told Brown to come to the back door, and he would slip them some food. “It was like treading water a lot of the time,” says Chaapel.

When not traveling together, the two kept in touch, with Brown openly expressing his admiration. In 1927, the first year of their correspondence, Brown wrote, “You are great for writing such inspiring letters. Many a young fellow must benefit from your attentions given in the midst of so much pressing work.”

Nature, art and black/white relations were frequent topics in their early exchanges. In 1927, Carver wrote, “I understand the race feeling is asserting itself in a number of schools and colleges in no uncertain way. Some schools recently have positively refused to have colored people appear upon their platform.”

A year later, Brown wrote, “You will be interested in some developments in the interracial work. The white students are asking now that groups of them be permitted to visit Negro schools like Hampton so that they can see what is going on and come to appreciate it more.”

Soon after Brown arrived at Bucknell in 1930, he wrote asking Carver to visit campus. Carver obliged in November 1930, with a talk on “The Inside of a Peanut,” bringing along his peanut exhibit and meeting with chemistry students in their lab.

The men shared a strong Christian faith and love of the land. Both had grown up on farms, Carver in Missouri, Brown in Tennessee, affording them a common language, Chaapel says: “It created a basis for their relationship.” Because her father had spent much of his youth working the fields side-by-side with African Americans, Chaapel says he was more open to interracial friendships than many in his era.

Brown addressed their common affinity for the natural world in a 1936 letter: “There is something refreshing about working in the soil and growing plants. If more people had the interest and the opportunity, more would be satisfied with the simpler side of life. It is a pleasure to eat during the winter the things which have grown on your own ground by the sweat of your brow.

“You have always maintained a universal interest in them all. I wish that I had some of the grasp of the world God has made and the spirit which sees in it the handiwork of God as an ever intelligent and comprehendible process. You have taught this to many of us.”