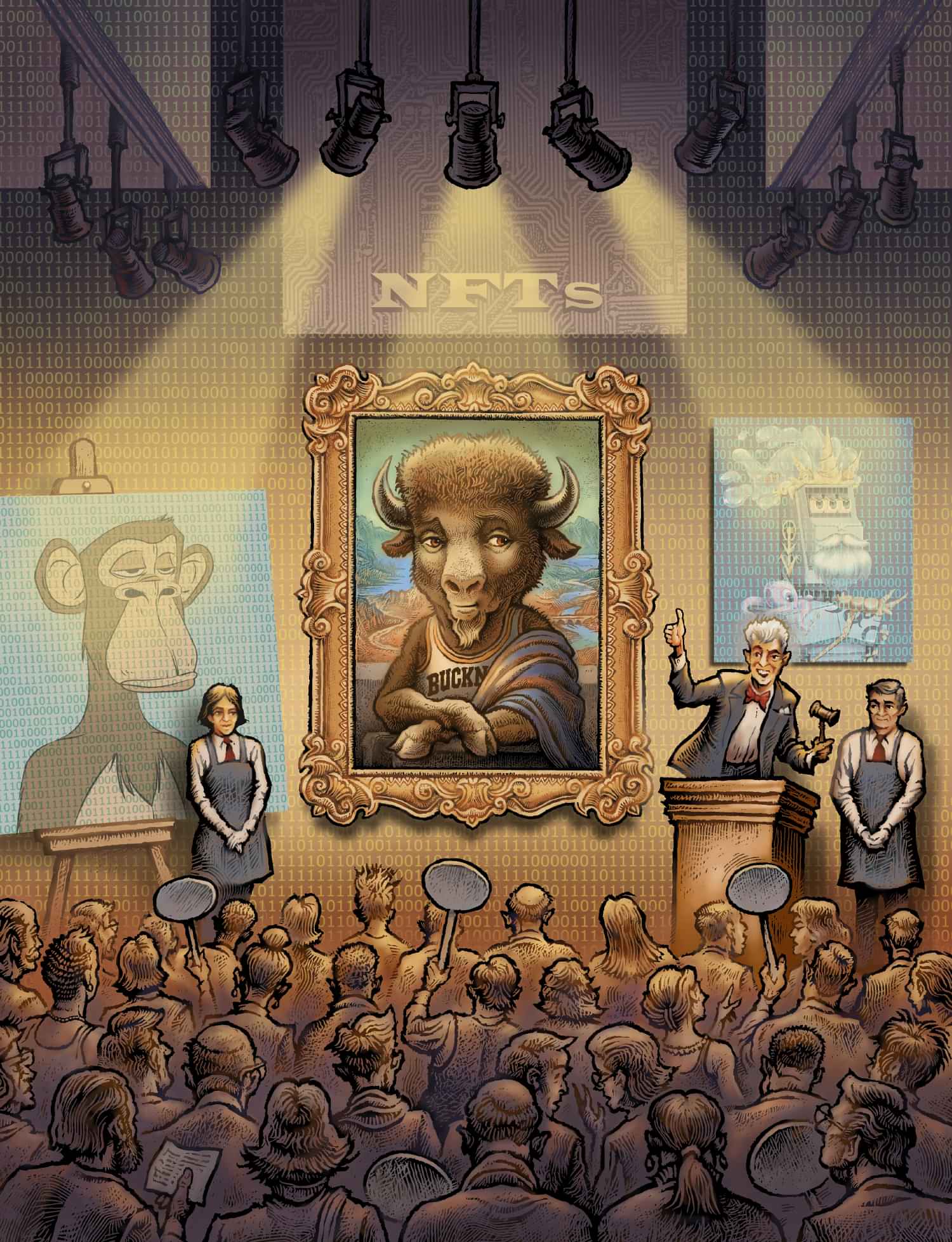

The Grand Art Bazaar

Bucknellians are shaping the debate.

illustrations by Phil Foster

The Grand Art Bazaar

Bucknellians are shaping the debate.

illustrations by Phil Foster

The National Basketball Association sells ones that feature highlight-reel plays. Major League Baseball sells them as a digitally enhanced version of the traditional baseball card. Musicians build fan clubs around ownership of them.

We’re talking about the economic phenomena known as non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, and they’re causing serious buzz — so much so that The Collins English Dictionary anointed “NFT” as its Word of the Year in 2021. Anything that can be created in a digital format — an image, a video, a sound clip, a 3D virtual reality session — can be made into an NFT. These unique digital collections of ones-and-zeroes use blockchain technology to store information as discrete, unalterable sets of data and stash them throughout the vast reaches of cyberspace. NFTs appear poised to revolutionize the worlds of art, music, finance and even the internet itself.

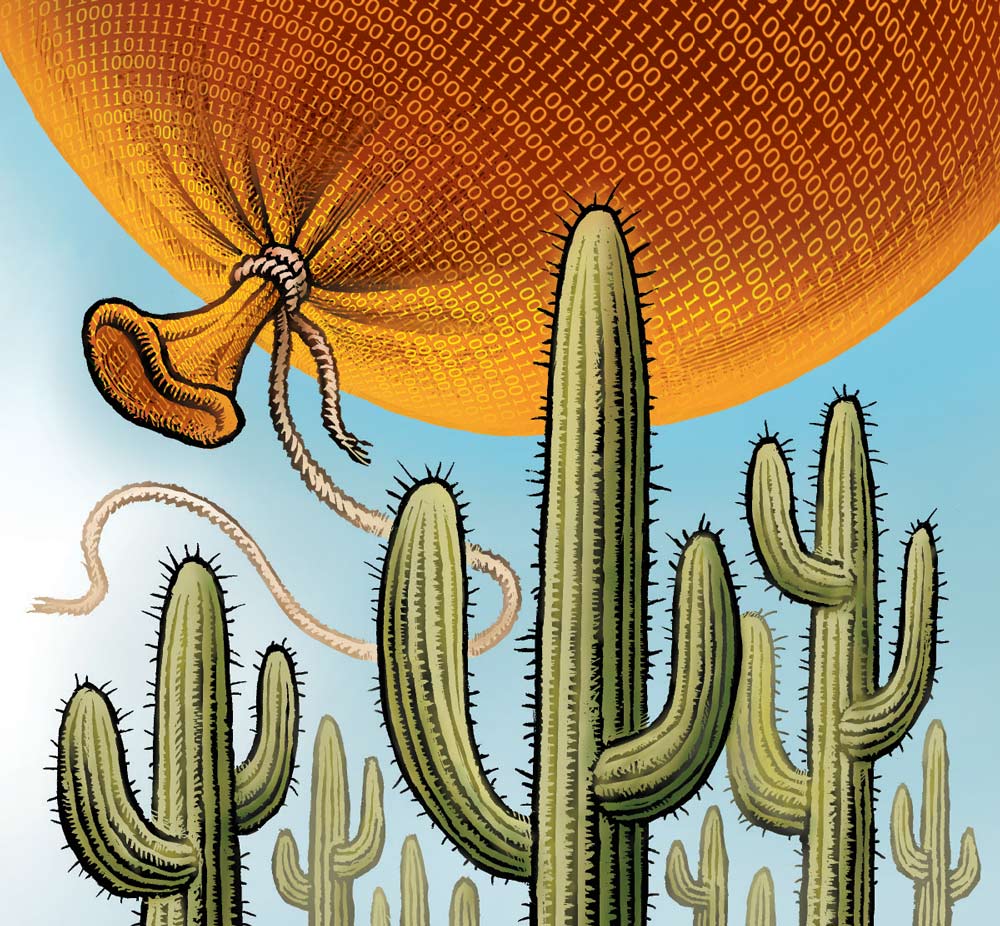

At least that’s the claim made by many early adopters of NFTs, who eagerly embrace the blockchain technology and cryptocurrency required to create, sell and distribute them. But skeptics question whether the proliferation of NFTs, and the eye-popping cryptocurrency sale prices that some command, are merely a speculative bubble driven by irrational hype — a modern version of the Dutch tulip craze of the 1630s.

Revolutionary art … or rank speculation?

NFTs are economically attractive to artists because, Maleki says, they can be structured to provide a royalty on any future resale of the work and let artists set terms for licensing of other economic uses.

They also offer great potential in the world of music, says Matthew Mehaffey ’97, a musician, conductor and professor at the University of Minnesota. None but a few superstars currently earn significant income from streaming services that play their music, and going on tour can be an exhausting way for lesser-known musicians to generate a little more income. NFTs, Mehaffey says, “can help musicians put more revenue from their intellectual property into their pockets.” Those NFTs might capture a special moment onstage or backstage, or provide a digitally enhanced, collectible “card” with links to special information about the musicians, or create a digital version of a fan’s ticket to an event, with a link to video of the performance. By selling NFTs, musicians can identify who their listeners are (which is not possible on streaming services like Spotify) and directly market other revenue-producing experiences to them. Mehaffey is hoping to help musicians realize that opportunity with his new venture, SuperFan NFT Studios, a consulting business that will offer a marketplace for NFTs.

While futuristic platforms like Nguyen’s and NFT works like those produced during Maleki’s residency are generating praise and, in many cases, profit (the residency art sold out within 15 minutes), Maleki says “it’s not so much about the monetary aspect. It’s about supporting talent in the digital art world.” He loves the sense of community that NFTs are fostering among artists and collectors, though he recognizes that “many buyers are in it for financial gain.”

And that’s the essential problem, according to skeptics. Looking at NFTs, they see a feverish form of speculation driven by cryptocurrency mania and astounding, worldwide levels of economic inequality. They see an elite class with way too much money looking for eye-catching ways to show off.

Bucknell Professor Karen McGrath, finance, notes that the NFT market is inextricably tied to cryptocurrency — it’s required to not only buy NFTs but also to create them, verify ownership of them on the blockchain and sell them. And she doesn’t see that changing. Until early 2022, crypto markets had been booming, producing billions in profits to many savvy or lucky investors who spent a nice chunk of their crypto gains on high-priced NFTs.

That was a boon for artists, but McGrath says it’s a sign NFTs have likely hit bubble territory. For these rich buyers, “there’s a lot of FOMO [fear of missing out]. It makes for a lot of questionable purchases. At some point, we might look back on this and go ‘Oh, my God, what were we thinking?’ ” Professor Luiz Felipe Perrone, computer science, shares that suspicion, saying NFTs are fueling “a speculation-based market that doesn’t produce any social good.” Validating those warnings, the value of leading cryptocurrencies had plunged drastically by mid-2022, dragging down the once-astronomical value of many NFTs and prompting questions about any value they had to begin with.

The value of “art”

The answers depend on who you ask.

Economists would say that the market value of something is determined by what a willing buyer pays a willing seller. Finance professor McGrath is struck by the astronomical prices, when what the buyer gets for their money is basically just bragging rights. “What’s valuable,” she says, “is the ability to say, ‘I am the one that owns this thing.’ ” (And, by implication, saying: “You don’t!”)

Doubters note that much of the current value is driven by the ego of wealthy NFT buyers. Economics major Sal Iovino ’24, writing in the Dec. 1 issue of The Bucknellian, noted that NFTs have no inherent value and asked whether their high-priced popularity indicates that the modern economy has devolved into a “virtual playground” for ultra-rich speculators. The reaction, he says, was civil but spirited. Some had no idea what NFTs are, but he also heard from fellow students who’ve already plunged into crypto investing, hoping to make a million dollars before they graduate.

Whatever the “value” of an NFT is, it can be very volatile. Freeman College of Management professor Eric Santanen notes that Jack Dorsey’s original tweet — the NFT of which sold for $2.9 million — is still on Twitter, where “anyone can make their own copy.” When the NFT of that tweet went back on the market, Santanen says, the auction was canceled because the high bid was only $14,000.

In the art world, NFTs are a “highly contentious” subject, according to Richard Rinehart, director of Bucknell’s Samek Art Museum. His Facebook feed is full of comments on them from colleagues in the art world, including artists and curators. “Half hate everything about NFTs and disavow them,” he says, “and half are leaning in hard, going full NFT.”

Rinehart says that digital art in general is changing the valuation game in some ways. Because it can be reproduced infinitely without loss of quality, “it can explode the notion that art is valuable because there’s only one. The value can come more from artistic merit, rather than scarcity.” McGrath says NFTs can shift some economic power toward artists because they can sell NFTs directly, bypassing the traditional gatekeepers who decide what is “art” and influence how valuable it is.

Speaking the Lingo

Cryptocurrency: A digital currency issued by a private entity rather than a government, using technology that can allow users to keep their identity and transactions confidential. The value of any cryptocurrency (there are some 19,000, most notably Bitcoin and Ethereum) may fluctuate wildly.

Blockchain: A decentralized internet security technology that treats digital data as unchangeable “blocks” that are distributed throughout cyberspace. Validators are typically paid in cryptocurrency for authenticating the information in these blocks. Sometimes called “an unalterable, distributed digital ledger or database.”

Proof of Work: The predominant type of blockchain security, where validators known as “miners” use huge computational networks to solve complex problems, which allows them to generate the next set of validated blockchain data and earn a reward paid in cryptocurrency.

Proof of Stake: An alternative blockchain validation technique. Potential validators “stake,” or put on deposit, an amount of cryptocurrency. The more cryptocurrency they stake, the more likely they will be randomly selected to validate a transaction and earn a cryptocurrency reward. Misbehaving validators will forfeit their stake, which incentivizes good behavior.

Web3: An emerging version of the internet in which users conduct activity using blockchain security instead of entrusting their information to social media companies, cloud storage providers and other powerful intermediaries.

So, are NFTs a new artistic medium, like photography once was? Or simply a new artistic technique, like one-point linear perspective? Or something in between?

Art collector Maleki says NFTs themselves are art, though he agrees that owning NFTs is a more “abstract enjoyment process” compared to physical artworks, which are displayed in abundance on the walls of his home. Rinehart, however, contends that an NFT “is only a complicated deed pointing to artwork.” Musician and NFT entrepreneur Mehaffey says NFTs are both and more.

Whatever NFTs are, the questions surrounding them — and the answers that result — may well produce profound changes in economies and societies across the globe.

The environmental question

All that electricity is needed because the blockchain that currently supports Bitcoin and NFTs runs on a technology called “proof of work.” Verifying transactions requires solving complex mathematical challenges, which can be done only with vast arrays of computers run by energy-hungry crypto “miners” operating 24/7. There’s a race to see who can solve the challenge the fastest and thereby collect a share of the verification fee, which is paid in cryptocurrency.

Samek Museum director Rinehart, like many of his peers, recognizes the problematic nature of the environmental footprint left by NFTs. He knows artists who refuse to create them because they say, “I can’t make my little piece of money at the expense of the planet.” His own view of NFTs is more nuanced. “If artists can marry art-making with the ability to make money,” he says, “that’s a good thing. I can’t knock it too hard.”

Brilliant minds are already pursuing a greener way of running the blockchain, though. The cryptocurrency that currently dominates NFT transactions, Ethereum, recently converted to a different validation technique, called “proof of stake.” Users become validators by “staking” their own cryptocurrency — putting it on deposit, so that it’s not available for other use and subject to forfeiture if they are caught trying to game or hack the validation system. The more they stake, the more likely they’ll be chosen by the chain’s validation algorithms and get paid in crypto for performing that service. Nguyen, the aspiring digital entrepreneur, says, “In the near future, everything will be using that more energy-friendly authentication method.” By some estimates, converting to proof of stake may cut blockchain electricity use by 99%. Nonetheless, that remaining 1% is part of a gigantic number that grows larger every day — one that could still strain a world on the edge of climate crisis.

More than a Pretty Picture

Mehaffey, the entrepreneurial musician and professor, expects his first commercial success with NFTs will come in a very different field: the liquor industry. He’s helping a new distillery whose whiskey is still aging and not yet ready for sale. The distillery plans to sell NFTs that entitle the holder to acquire the whiskey after the three-year aging process is complete and collect royalties when it is resold. His client will produce early income, and complicated laws governing the traditional liquor trade will not apply to the arrangement.

It’s an example of how the blockchain can foster the potentially revolutionary innovation that boosters call “decentralized finance,” or “DeFi.” They say DeFi is a shining example of what the new generation of internet technology, known as Web 3.0 or Web3, can deliver. (Web 1.0 was the early internet, offering limited, complicated electronic interactions and mostly static, read-only content. Web 2.0 is today’s pan-global interactive network, connecting billions of users, largely through tech companies that earn billions of dollars from exploiting users’ data.)

Web3 evangelists say its “permissionless” blockchain technology will execute transactions and handle information in a way that’s open and easily accessible to any user, without need for the big tech companies and software that scoops up your data so they can monetize it. You’ll own your data and information. You’ll hold the digital keys to it, not some third-party trustee who may or may not be trustworthy (especially in how they exploit your data). You’ll create and control your accounts — no one can freeze or suspend them.

DeFi enthusiasts believe Web3 will allow easy, efficient and secure financial transactions, in a process as simple as using email or your phone or texting. Businesses may find it especially useful for making and enforcing contracts and authenticating claims that boost the value of a product, such as “sustainably produced” or “not from sweatshop labor.”

A new set of Web3 technological intermediaries may well emerge, but the hope is they will lack the power of today’s tech giants. If users are unhappy with their service in Web3, they’ll easily be able to take their business elsewhere.

Economics major Yuki Yao ’25 had an internship this summer in his hometown of Tokyo with a Web3 startup. Yao expects blockchain-based internet applications will be especially useful in places where social trust in intermediaries (like banks, accountants and lawyers) is lacking because the blockchain provides another secure way to verify transactions.

Management professor Santanen isn’t sure that NFTs will have staying power, but he thinks the underlying blockchain technology definitely has potential. In today’s economy, he says, “we use third-party intermediaries to establish trust, and the blockchain has the potential to disrupt that.”

If Web3 and DeFi are going to take off, though, there are some challenges to work out.

After the NFT marketplace OpenSea did an internal review showing that 80% of NFTs listed there were plagiarized, counterfeit or spam, attorney and investor Michael Goldstein ’81 was not surprised. A special adviser to an NFT venture called Veriken, he says the early phase of NFTs has been heavy on financial speculation, and “you were bound to get lots of scammers.” He sees a need for better counterfeit detection and transparency around prices and fees. During his one small foray into crypto investing, he says he was shocked at how big a bite the fees took.

“I’m hopeful the next phase will focus on what NFTs are really useful for,” Goldstein says. Among the things his venture, Veriken, is working on is a “licensing wizard” that will help collectors and creators protect the intellectual property embodied in NFTs as the tokens change hands.

Inevitable Extinction?

Attorney Goldstein’s colleague at Veriken, CEO Chris Clason, is realistic about the security and environmental challenges for this new technology, but he’s also optimistic about surmounting them. Proof of stake will become the blockchain standard, cutting the wasteful energy use, Clason predicts, and the security issues will get worked out. “I think Web3 will get there, and all the snake oil salesmen will find somewhere else to go.”

While Web3 and the blockchain are still evolving in important ways, NFTs are a hot thing in the art world, at least for now. One benefit they bring, says museum director Rinehart, is offering a more reliable way to document the authenticity of works. “Blockchain and NFTs have got to be more secure than the paper documents we’ve been relying on for centuries.”

But those digital works of art also rely on rapidly evolving technology and complicated equipment, which Rinehart says raises an important question: Will these works, which are ultimately only ones and zeros somewhere in cyberspace, survive for posterity? Over time, high-tech equipment fails or becomes obsolete; software rapidly changes and can become unusable if not simply abandoned.

“Does anyone remember HyperCard?” Rinehart asks, referring to an Apple software popular in the 1990s. “There was oodles of content on it from artists, scientists, researchers, teachers. It was a whole universe. All that information’s gone. HyperCard was really big, and now it’s all gone.”

Preservation is just one of many challenges posed as NFTs, blockchain and Web3 continue to evolve and work their way deeper into daily life. As entrepreneurs and investors drive these new technologies, there will be benefits and costs, winners and losers, changes good and bad, in both the economy and society as a whole. The debate about the pluses and minuses of this technological ferment and how it should be managed will be vigorous, and Bucknellians will continue to shape the future that results — whatever it may be.

If you’re wondering: Bucknell gladly accepts donations in the form of cryptocurrency. As always, the value of a gift is determined by the donor in accordance with relevant tax law.