icture the scene: A camera pans over New York, the skyscrapers illuminated and glistening at night, before the director cuts to a plush hotel room overlooking the city. Inside, a svelte man in his early 50s relaxes in his white bathrobe on a couch — cola in hand and Japanese wrestling livestreaming on his laptop.

Then his phone rings. When Harold Meij ’86 answers, he receives an offer no Japanese wrestling fan could refuse — the opportunity to become the CEO and president of Japan’s largest and most popular wrestling organization, New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Meij said yes, and in 2018 became the organization’s first non-Japanese leader.

In most companies, new appointments are announced with an internal memo, a press release or maybe even a press conference. With all the showmanship one would expect of professional wrestling, Meij starred in an introductory video, one that ends with the Dutchman delivering a statement of intent to the sport’s ever-growing legion of fans: “I want to bring New Japan Pro-Wrestling to the next level.”

Why did Meij get that call? The answer, as he explains during an interview at his office in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward, is that New Japan Pro-Wrestling wanted someone equally at ease with business not only in Japan but throughout the rest of the world. The multilingual Meij fit that bill, having been raised in Japan and Indonesia by Dutch parents before attending Bucknell as an international student.

Diversity is a word that Meij often mentions when talking about the fighting styles of wrestlers and their individual characteristics and backgrounds — New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s fighters are a multiracial and multinational group — but also when talking about his time at Bucknell. He was drawn to the University by the opportunity to pursue the liberal arts as well as professional studies by majoring in business administration and Japanese/East Asian studies. Bucknell also is where he learned to embrace diversity.

icture the scene: A camera pans over New York, the skyscrapers illuminated and glistening at night, before the director cuts to a plush hotel room overlooking the city. Inside, a svelte man in his early 50s relaxes in his white bathrobe on a couch — cola in hand and Japanese wrestling livestreaming on his laptop.

Then his phone rings. When Harold Meij ’86 answers, he receives an offer no Japanese wrestling fan could refuse — the opportunity to become the CEO and president of Japan’s largest and most popular wrestling organization, New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Meij said yes, and in 2018 became the organization’s first non-Japanese leader.

In most companies, new appointments are announced with an internal memo, a press release or maybe even a press conference. With all the showmanship one would expect of professional wrestling, Meij starred in an introductory video, one that ends with the Dutchman delivering a statement of intent to the sport’s ever-growing legion of fans: “I want to bring New Japan Pro-Wrestling to the next level.”

Why did Meij get that call? The answer, as he explains during an interview at his office in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward, is that New Japan Pro-Wrestling wanted someone equally at ease with business not only in Japan but throughout the rest of the world. The multilingual Meij fit that bill, having been raised in Japan and Indonesia by Dutch parents before attending Bucknell as an international student.

Diversity is a word that Meij often mentions when talking about the fighting styles of wrestlers and their individual characteristics and backgrounds — New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s fighters are a multiracial and multinational group — but also when talking about his time at Bucknell. He was drawn to the University by the opportunity to pursue the liberal arts as well as professional studies by majoring in business administration and Japanese/East Asian studies. Bucknell also is where he learned to embrace diversity.

icture the scene: A camera pans over New York, the skyscrapers illuminated and glistening at night, before the director cuts to a plush hotel room overlooking the city. Inside, a svelte man in his early 50s relaxes in his white bathrobe on a couch — cola in hand and Japanese wrestling livestreaming on his laptop.

Then his phone rings. When Harold Meij ’86 answers, he receives an offer no Japanese wrestling fan could refuse — the opportunity to become the CEO and president of Japan’s largest and most popular wrestling organization, New Japan Pro-Wrestling. Meij said yes, and in 2018 became the organization’s first non-Japanese leader.

In most companies, new appointments are announced with an internal memo, a press release or maybe even a press conference. With all the showmanship one would expect of professional wrestling, Meij starred in an introductory video, one that ends with the Dutchman delivering a statement of intent to the sport’s ever-growing legion of fans: “I want to bring New Japan Pro-Wrestling to the next level.”

Why did Meij get that call? The answer, as he explains during an interview at his office in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward, is that New Japan Pro-Wrestling wanted someone equally at ease with business not only in Japan but throughout the rest of the world. The multilingual Meij fit that bill, having been raised in Japan and Indonesia by Dutch parents before attending Bucknell as an international student.

Diversity is a word that Meij often mentions when talking about the fighting styles of wrestlers and their individual characteristics and backgrounds — New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s fighters are a multiracial and multinational group — but also when talking about his time at Bucknell. He was drawn to the University by the opportunity to pursue the liberal arts as well as professional studies by majoring in business administration and Japanese/East Asian studies. Bucknell also is where he learned to embrace diversity.

“Going to Bucknell gave me a great deal of confidence, and the diversity also served me well — not just the mix of overseas students and people from all over the country, but the range of subjects,” Meij says.

“Thinking about Bucknell, my parents at that time were still living in Indonesia, so I went to the U.S. all alone,” Meij says. “That experience prepares you for change — you aren’t afraid of making changes or of going it alone. That is something I’ve taken with me throughout my career.”

His drive for career sucess led him to stints at Coca-Cola and Heineken’s Japan divisions before becoming the first non-Japanese to lead Takara-Tomy (one of Japan’s oldest and largest toy companies).

New Japan Pro-Wrestling, however, posed a new kind of challenge for Meij. At Heineken, he had been part of a two-person team seeking to make inroads in Japan. At Takara-Tomy, he had reawakened an ailing giant and brought it to record annual operating profits of 13.1 billion yen (equal to about $124 million), something he achieved by introducing a trio of concepts: creating “ageless” products to target all age groups, going “borderless” by exploring overseas markets and making product development an “endless” cycle of evolution. At New Japan Pro-Wrestling, he was taking control of a major sport with a loyal and passionate fan base that had grown domestically and internationally for eight years.

His first task was laying the groundwork for upcoming changes in the way things had been done in the past. “People in their very nature don’t like change. It’s even harder when you are successful,” Meij says. “So in my first year, I had to focus on building a relationship with the fans to create a platform for change. I had to show them that I cared about the sport, that before becoming CEO, I was a fan, too.”

Meij accomplished that in his first year by attending as many New Japan Pro-Wrestling events in Japan and overseas as possible, making sure to spend time meeting and greeting fans and hearing their feedback firsthand. Posing for selfies, stopping to chat about wrestling and remembering which fans he met before are all part of the job. This emphasis on mingling with the public is another departure from his previous corporate roles.

To demonstrate how he engages fans, Meij pulls a stack of stickers from his jacket pocket. The stickers feature various caricatures of Meij — drawn, he says, by a fan — that he hands out when meeting wrestling aficionados. Now collector’s items, some of them sell online for as much as $25.

To understand the place wrestling (of the nonsumo variety) has in Japan, it’s important to know the history of the sport there. Wrestling took off in Japan in the 1950s, when the country was still on its knees after its defeat in World War II.

“The crowds were massive,” Meij says, as he displays a black-and-white photo on his laptop. This circa-1955 image of the Shimbashi area of central Tokyo shows the streets packed with thousands of people gathered to watch an outdoor broadcast of a fight featuring the first Japanese wrestling superstar, Rikodozan. “Back then, wrestling was one of the biggest forms of entertainment, and it gave people a break from postwar hardships,” Meij explains.

Fights often pitted local heroes against American bad guys, prompting some cultural commentators to suggest that wrestling helped some Japanese regain an element of national pride. More than anything, however, it was simply fun to watch. In the 1970s and ’80s, when most Japanese households had a TV, wrestling became a prime-time favorite. The big stars of the day — like the chiseled-jawed Antonio Inoki, who founded New Japan Pro-Wrestling in 1972 — became cultural icons. Inoki’s “Ichi ni san da” (a play on ichi, ni, san — meaning one, two, three — and the word thunder) is one of Japan’s classic catchphrases.

In the 1990s and 2000s, however, viewing waned. Japanese pro wrestling slipped away from prime-time TV slots as more varied broadcasting and rival forms of entertainment took root, although a core fan base kept the sport going. New technology allowed New Japan Pro-Wrestling to bounce back, as it was now possible to broadcast digitally and connect with fans directly through social media. New Japan Pro-Wrestling went from slump to renaissance to new heights. And not just in Japan.

“We have about 150 matches annually in Japan and other parts of the world, but we can never double that because the wrestlers need rest, so we needed to go digital to grow,” Meij says. “We have a streaming service [called NJPW World] where you can watch all the matches live or replayed wherever you are. We have interviews with wrestlers and other content, as well as a YouTube channel and podcasts. Now, about half of the subscribers to our streams are outside of Japan.”

To convey how New Japan Pro-Wrestling has grown beyond Japan, Meij points to the sport’s first-ever match at Madison Square Garden this April. According to media reports, all 16,000 tickets for the event sold out in 16 minutes. In June, Meij and New Japan Pro-Wrestling staged a two-date tour of Australia, followed by events in Washington state and California. Meij says a first stand-alone London event was also scheduled for Aug. 31 at the Copper Box Arena in the East End.

Currently, about 20 of the organization’s wrestlers are non-Japanese, but that may change with the opening of dojos (training facilities) in Los Angeles and Australia. In dojos, future New Japan Pro-Wrestling stars — called Young Lions — live and train together much as sumo wrestlers do.

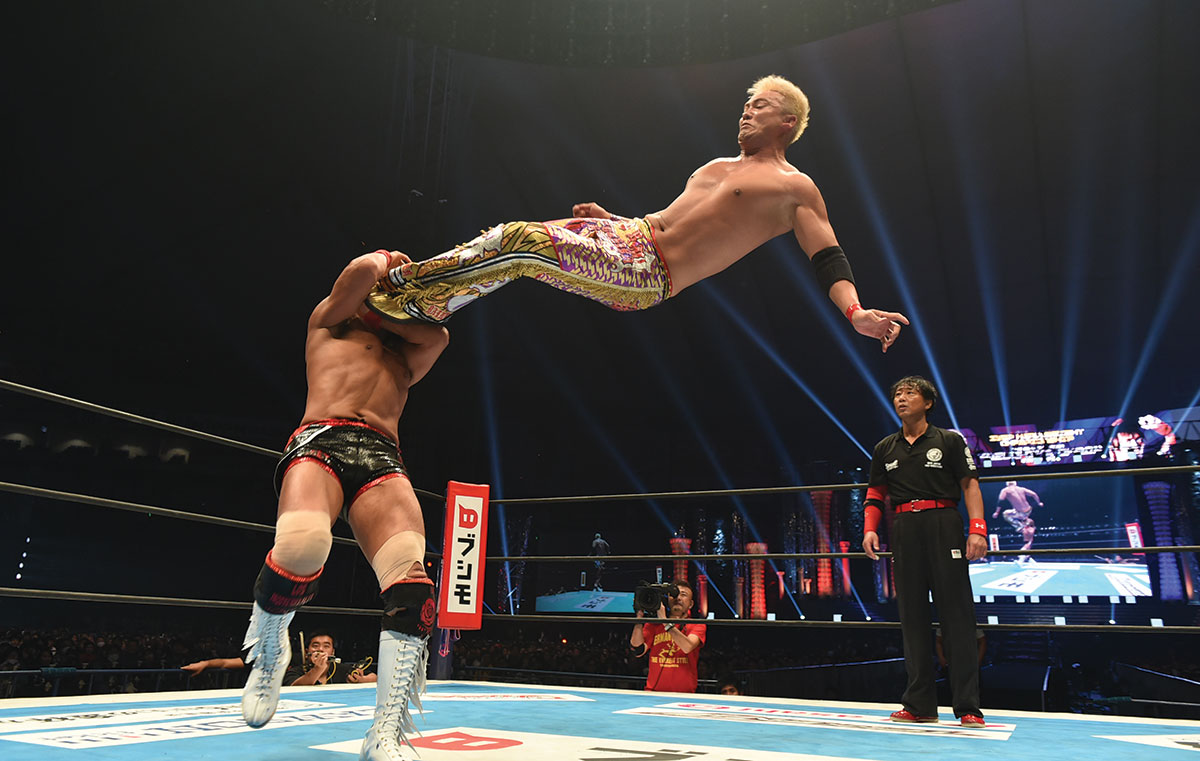

Given that the United States has its own forms of wrestling, as do many other countries where New Japan Pro-Wrestling is growing, what is it about Japanese wrestling that Meij thinks resonates with fans outside of Japan? It’s different, for starters. While showmanship is a hallmark of wrestling in both the United States and Japan, New Japan Pro-Wrestling lacks trash talking, and gimmicks such as wrestlers hitting each other with chairs are kept to a minimum. And there’s tradition.

“New Japan Pro-Wrestling has been going for 50 years, and there’s the connection to the whole bushido [the code of honor and morals developed by the samurai] thing. You know, we train in a dojo. And when we export pro wrestling, we keep it as Japanese as possible — we do the stage introductions overseas, for example, in Japanese,” Meij says.

“We also have a great variety of wrestlers,” he adds. “We have wrestlers who use power, but move more slowly, and we have aerial specialists like the Aerial Assassin. We have technical wrestlers who are smaller but like an anaconda when they get you. We have all-arounders who can do a bit of everything and a few who are comical — they do silly things to lighten the atmosphere. That’s the beauty of wrestling; there is no right way to do it or watch it. There’s something for everyone.”

The demographic breakdown of New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s fans in Japan indicates one reason the organization now has an 80 percent share of the domestic professional wrestling market — impressive given that there are dozens of pro-wrestling promotional organizations in Japan. Globally, it is second only to the U.S.-based WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment). Approximately 40% of Japanese fans are women mainly in their 20s to 30s, 10% are children 12 and under, and 50% are men, mainly in their 30 and 40s.

Since Meij took the helm, fans in Japan and overseas have enjoyed increased access to the flamboyant stars of the show. “One major difference for me at New Japan Pro-Wrestling is that in previous roles I was selling brands. Now I am promoting wrestlers — real people,” Meij says.

“One way we try to create more pathways into the sport is to appeal to not just what happens in the ring, but also what is outside it,” he explains. “That means presenting our wrestlers in a human way. We put them on game shows and TV shows not directly related to the sport — we were one of the first sports to do that in Japan. They all have their own Twitter accounts, run by themselves. They choose their own nicknames and costumes. We don’t manufacture them — each expresses their own character in a genuine way, and that diversity gives fans more to choose from. It’s real.”