Grisel was supposed to replicate in mice the pain-relieving effects of earlier research, but her results were inconsistent. A breakthrough occurred when she broke the results down by sex: The drug eased pain in male mice, but in female mice, the drug actually intensified pain.

“It was a profound difference,” Grisel says. The drug’s effect worked on “a very basic mechanism, so I can see why [the drug company] thought it would work the same in women and men.”

Grisel called her contact at the drug company to relay her findings and received an unexpected response.

“He told me to put the women’s information in a footnote and share the male data in graphs,” she says. “I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, what have I become?’ ”

The experience reinforced Grisel’s uncommon practice of regularly studying how drugs affect the sexes differently.

Though there has been slow improvement since Grisel published her Dextromethorphan findings, scientific research largely continues to ignore half the world’s population. Things are beginning to change, but it bothers the scientist in Grisel that females are routinely left out of scientific studies.

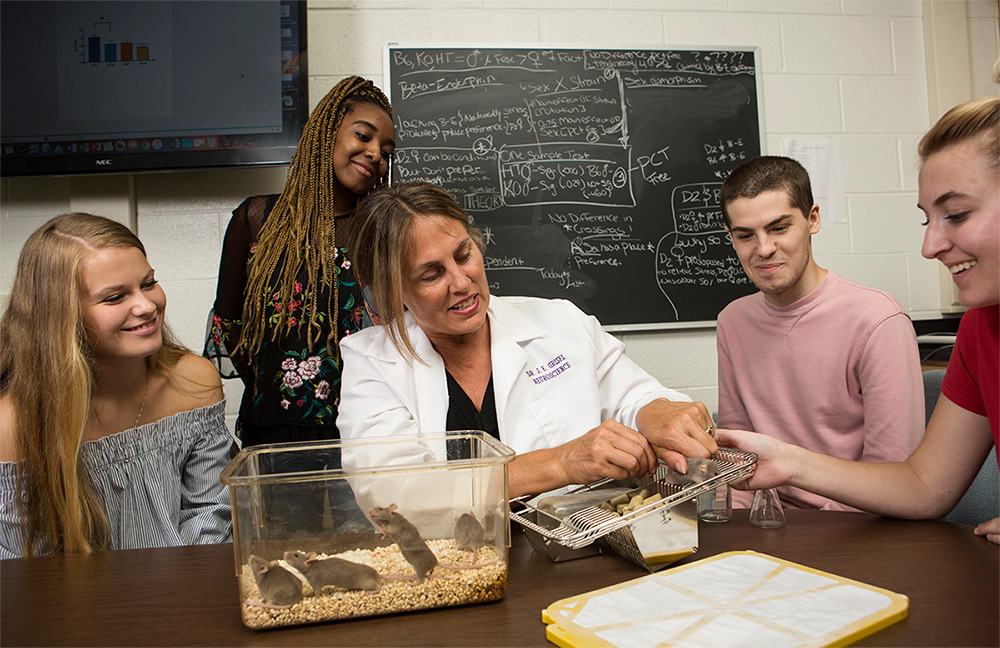

“I still get papers to review on research that only studied males,” Grisel says. “I have to convince my students and colleagues that it’s important in terms of the integrity of science to study both, because females are, after all, about half the population.”

The experience blazed a research path for Grisel, who had studied addiction but wanted to dig into the antecedents of addiction.

Grisel was convinced sex significantly influenced addiction. To prove it, she studied how male and female mice consume alcohol differently when stressed. Grisel gave the mice access to running wheels and alcohol. When she locked the wheels so they wouldn’t turn, female mice doubled their alcohol intake.

“The females would voluntarily consume nearly enough alcohol to pass out, but consumption by male mice wasn’t affected,” she says of her findings, published in 2014 in Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research.

The study showed female mice with low beta-endorphin levels were more likely to consume more alcohol, more quickly than male counterparts. Female mice also escalated to addictive behavior — preferring alcohol over food and water — sooner than males.

Grisel says this study highlights the role genetics play in explaining why some people become addicted while others do not, and perhaps also why women are more likely than men to binge drink, progress to alcoholism sooner and experience declining health sooner when addicted. It also reinforces the point she learned years ago from the Dextromethorphan study.

“We know women feel more pain, we know women feel more stress, and we know women self-medicate more often. The bigger point, though, is that we won’t understand something as complex as addiction unless we dig deeply into things like sex differences.” — Susan Lindt